Research Paper Title and Abstract Optimization: The Complete Guide

Your title and abstract are the parts of your scientific paper that get read first, by both people and systems. Editors skim them to decide whether your manuscript fits the journal and merits review. Search tools and databases use them to decide whether your work matches a query. If either one is vague, jargon-heavy, or misaligned with your actual contribution, strong research can become hard to find, hard to trust, and easy to skip. That is why research paper title and abstract optimization should be treated as a final-stage audit before you submit.

A useful way to think about this is a storefront analogy. Your title is the signage; it tells the right reader they are in the right place. Your abstract is the window display; it convinces them that the paper is worth opening and that the claims are supported. When the signage is unclear or the window display does not match what is inside, you lose the reader at the exact moment attention is most scarce.

If you are a “polisher”—someone with a near-complete draft who is approaching submission—this guide is for you. You are not trying to invent a title or draft an abstract from scratch. You are trying to make sure your paper is discoverable in places like Google Scholar or PubMed, and that a busy editor can understand your contribution quickly and accurately.

If you are also preparing the wider submission package, see Submitting a Paper to an Academic Journal: A Practical Guide for a step-by-step view of screening, peer review, and revision stages.

This guide shows you how to work through a systematic audit process for your research paper’s title and abstract that you can apply to any discipline. You will learn how to front-load the right terms without making the title unreadable, how to build an abstract that moves cleanly from context to contribution to results, and how to align keywords across the title and the first lines of the abstract without drifting into keyword stuffing. By the end, you will have a practical pre-submission checklist you can use every time, and you will be able to spot the common title and abstract patterns that trigger fast editorial rejection.

If you want to speed up the same audit, you can also run your draft through thesify’s title and abstract feedback and use the comments as a structured revision loop, rather than relying on instinct or last-minute tinkering.

How Academic SEO Works: Google Scholar and PubMed

Academic SEO (search engine optimization) means your paper should appear when the right reader searches for the topic, method, population, or key construct you actually study.

In scholarly search environments, discoverability is is driven by whether your title and abstract contain the terms that readers use, and whether your wording makes those terms unambiguous.

Two audiences evaluate your title and abstract at the same time:

Machines (search engines and databases) match queries to words and bibliographic metadata.

Humans (editors, reviewers, and time-poor readers) make fast judgments about fit, novelty, and credibility.

You will get better outcomes when you treat academic SEO as two checks you can run deliberately.

Google Scholar: A Crawler That Depends on Clear Metadata

Google Scholar is crawler-based. It discovers scholarly content by scanning the web, then identifying bibliographic information to build a record for your paper. Google Scholar’s indexing guidance is explicit: computer-readable bibliographic metadata matters because it helps Scholar correctly identify your title, authors, and citation details.

What this means for your title and abstract:

Scholar needs stable, recognizable data to index and display your work correctly.

Because Scholar often displays results in dense lists, your title is doing retrieval work and decision work at once.

A reader is scanning quickly, and Scholar is matching quickly.

Practical implication:

Choose one “main term” (your core construct, phenomenon, or method label) and make sure it appears in the title in a form that a researcher would actually search.

Do the same in the abstract’s opening lines.

This is not gaming an algorithm; it is about matching the language of your field.

Because discoverability is the first hurdle in the editorial triage process, you can find further details on how databases and journals handle your metadata in our broader guide: Submitting a Paper to an Academic Journal: A Practical Guide.

PubMed: Query Mapping and MeSH

PubMed behaves differently because it is both a search interface and a gateway to MEDLINE indexing practices. Two mechanics matter for title and abstract optimization:

Automatic Term Mapping (ATM): PubMed does not simply search your raw words. It often maps query terms to other forms, including Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and related terminology, depending on how the query is entered.

Field searching: PubMed supports tags that explicitly search within the title and abstract fields (e.g., [tiab]).

What this means for your title and abstract:

If your paper uses standard biomedical terminology (including common synonyms), it is easier for PubMed’s search behavior and downstream indexing layers to connect readers to your work.

Conversely, if your title relies on undefined abbreviations, readers may still find you, but they are less likely to click, and they may misinterpret what you actually studied.

Practical implication:

If you work in a MeSH-heavy area, you do not need to write “for MeSH,” but you should prefer the term your field treats as the standard label.

Introduce any necessary abbreviation only after the full term appears at least once in the abstract.

Machine Readability vs. Human Readability

To optimize effectively, you must satisfy two distinct checks:

Machine Readability (Retrieval): Can a database match your paper to a specific search query? This depends on using the standard vocabulary of your field rather than lab shorthand.

Human Readability (Screening): Can an editor grasp your findings in under 60 seconds? This requires specificity—giving the reader a clear, early reason to keep reading.

A reliable optimization workflow separates these two checks.

1. Machine readability (The Retrieval Check)

Can a database or search engine match your record to the query a relevant reader would type?

Do your title and abstract use the vocabulary that appears in the literature (not your lab’s internal shorthand)?

Do the title and the first sentences of your abstract include your main term in a direct form?

This is what people mean when they say “keywords.” It is not keyword stuffing; it is the alignment between how your field searches and how your paper is described.

2. Human readability (The Screening Check)

Can an editor understand, in under a minute, what you did and what you found?

Does your abstract signal the contribution early, rather than spending half the word count on scene-setting?

Does the title promise something the abstract actually delivers?

This is where hooks matter, but “hook” in academic writing is not hype. It is specificity. You are giving the reader a clear, early reason to keep reading.

In the next section, you will apply these principles to your title first, because it functions as the primary label for both search matching and editorial triage.

How to Optimize Your Research Paper Title

Title optimization requires ensuring the right reader can:

Find it in search results

Understand what it is, quickly, from a single line

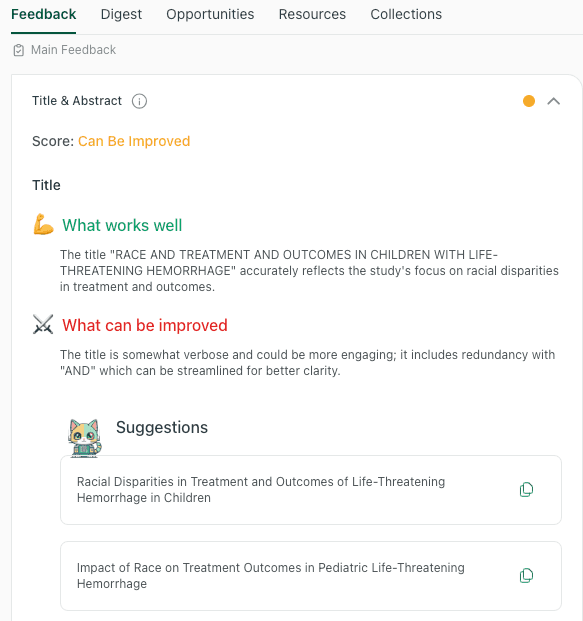

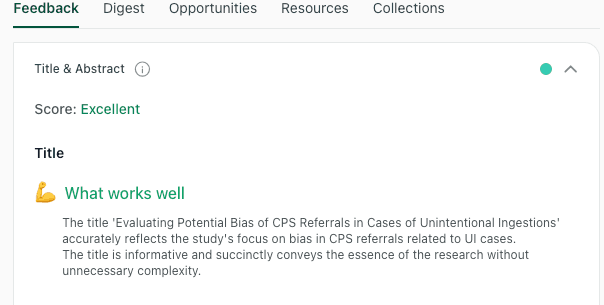

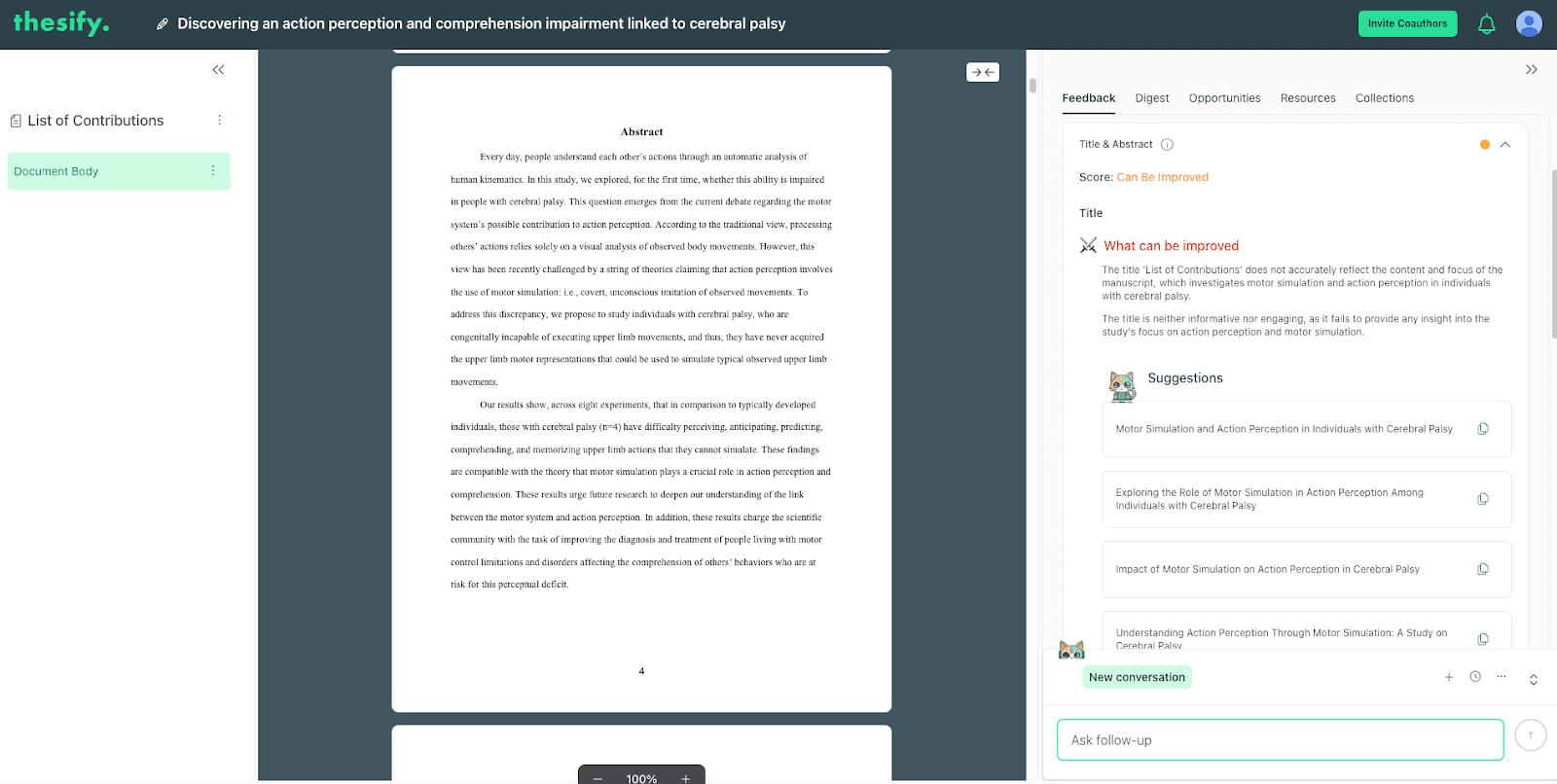

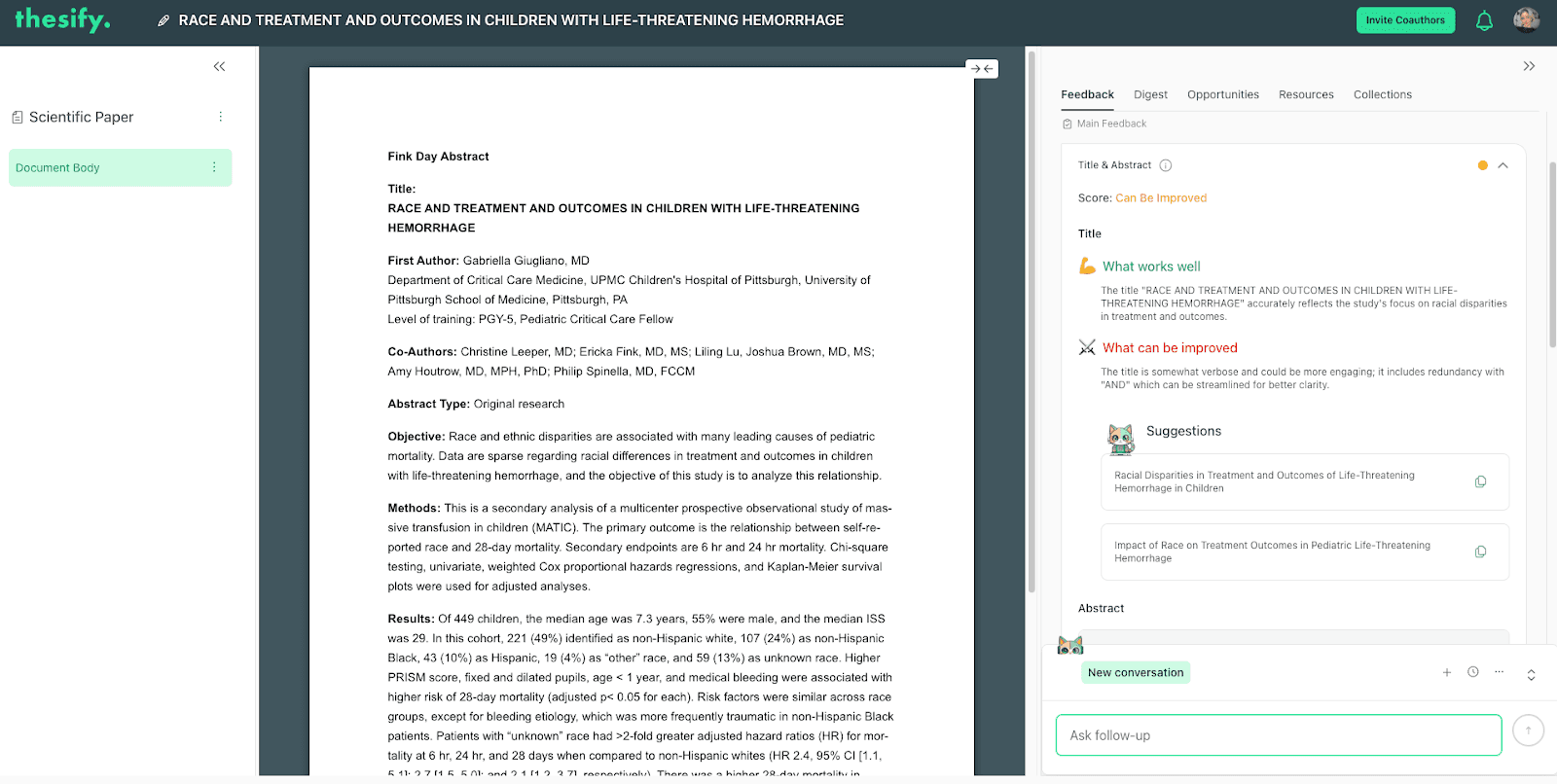

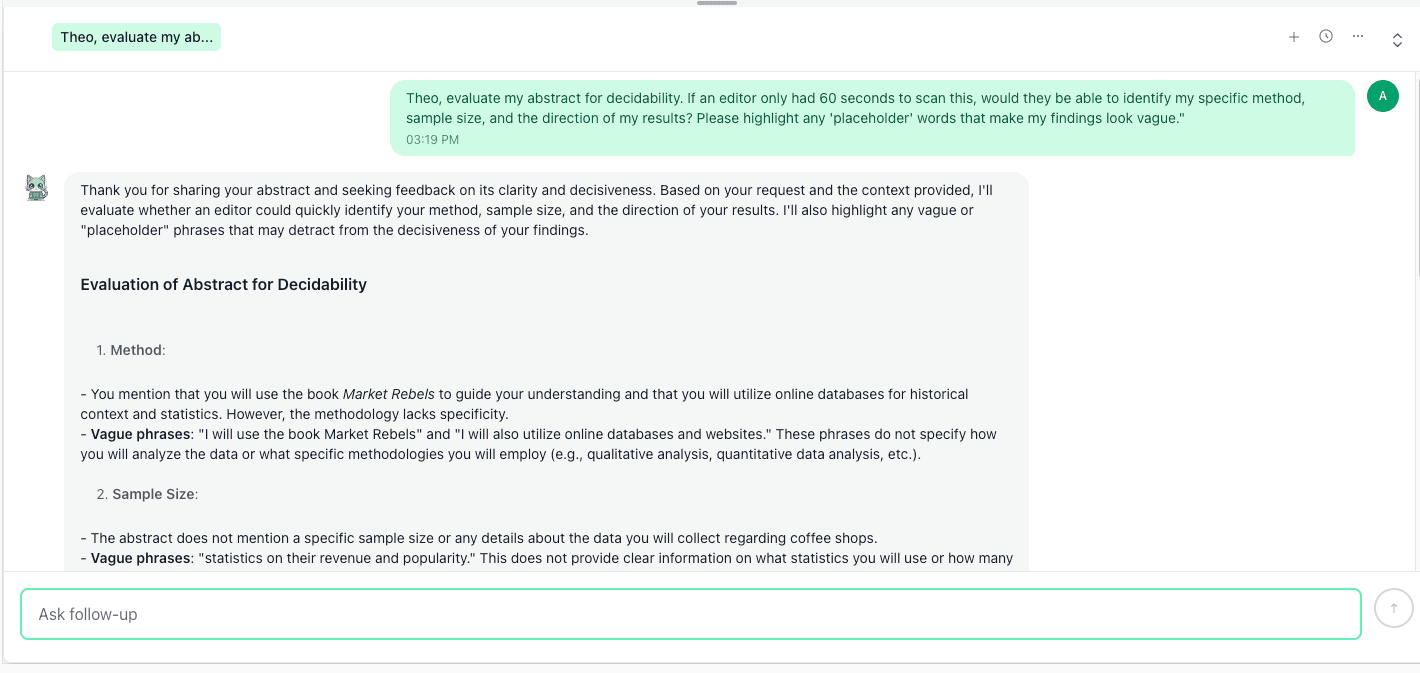

Example title feedback in thesify, highlighting what works well, what can be improved, and suggested rewrites.

A good working assumption is that your title is doing two jobs at once:

Retrieval: It must contain the terms people actually search for.

Screening: It must signal scope, design, and contribution without forcing the reader to decode jargon.

The safest way to improve your title is to treat it like a revision task with constraints. You are trying to maximize clarity per word. As shown in the feedback example below, even a technically accurate title can often be made more engaging through structural refinement.

Instead of guessing if your title is too lengthy, use thesify’s feedback to find a balance between clarity and engagement.

For a broader look at starting your draft with clear signals, see How to Write a Scientific Paper in 2025: Ideas First.

The “Front-Loading” Rule: Keywords in the First 65 Characters

Many scholarly search interfaces and journal platforms display truncated titles in lists or on mobile devices, so the earliest words carry disproportionate weight. Author guidance from major publishers often recommends placing one to two main keywords early in the title (sometimes phrased as “within the first 65 characters”) specifically so they remain visible in search displays.

Use this as a practical revision test, not a rigid character-count exercise:

Identify one primary term that a relevant reader would type into Google Scholar or PubMed (construct, method, population, or condition).

Make sure that term appears in the first 10 to 12 words of your title, ideally as close to the beginning as your syntax allows.

Remove “throat-clearing” openers that push the real topic later (e.g., “A study of,” “An investigation into,” “Towards understanding”). They rarely add meaning.

A quick rewrite pattern that works across fields:

Start with what the paper is about (phenomenon, population, object).

Add what you did (design, approach) only if it materially narrows interpretation.

Add context (setting, domain) only if it changes what a reader expects to learn.

If you want a simple guardrail, aim for a title length that stays readable. Many writing analyses and style discussions converge on titles in the range of roughly 10 to 12 words as a common target, although norms vary by field and journal.

Descriptive vs. Declarative Titles: When to Use Which?

Most research articles use descriptive titles. They name the topic and scope without stating the outcome. Declarative titles state a main finding directly. While declarative titles can work well in some venues, they carry a higher risk of sounding like an overclaim if your finding is conditional, context-bound, or statistically nuanced.

How to decide:

If your central result can be stated in a single clause without qualifiers, and your field accepts assertive titles, a declarative title can be defensible.

If your results require hedging, moderation, or multiple conditions, descriptive is usually the safer choice.

Title Type | What It Does Well | Main Risk | Use It When |

Descriptive | Signals topic and scope without overclaiming. | Can be generic if too broad. | Your results are nuanced, conditional, or field norms prefer caution. |

Declarative | Makes the main takeaway immediately legible. | Can imply causality or certainty you did not test. | Your core result is unambiguous and your target journal regularly publishes assertive titles. |

A useful compromise is to keep the title descriptive and allow the abstract’s first two sentences to carry the “so what,” because you can express contribution without locking yourself into a single headline claim.

The Colon Strategy: Using Subtitles for Context

Colons let you combine a short, readable lead with a clarifying subtitle. This often helps you balance human readability with machine retrieval:

Lead phrase: The hook or core construct.

Subtitle: The specific context, method, population, or dataset.

Example structure:

Core Topic or Claim: Context, Population, or Method

Colons are common in academic titles, and preference studies suggest readers often like the added context. Evidence on whether colons increase citations is mixed. Some analyses find no consistent effect overall, while others report small associations in specific disciplines.

So treat the colon as a clarity tool. Use it when your main term is broad and you need to specify domain or design. Avoid it when you are using it to hide vagueness (e.g., “Exploring,” “Investigating”) or when the subtitle becomes a second title packed with abbreviations.

Title Mistakes to Avoid: Jargon and Acronyms

If readers cannot parse your title quickly, they are less likely to click, cite, or even correctly classify what your paper is about. This is where “optimization” becomes a restraint exercise: you remove language that is locally meaningful in your lab or subfield but not broadly legible.

1. Jargon and specialized terminology

A large study in a multidisciplinary niche found that heavier jargon use in titles and abstracts was associated with fewer citations, which is consistent with the idea that hard-to-read framing reduces reach beyond a narrow audience. To check if your terminology matches your target field, see Understanding Differences in Academic Writing Across Disciplines.

Fix: Replace discipline-internal labels with the term you see in article keywords across your target journals. Prefer concrete descriptors over theoretical shorthand in the title.

2. Acronyms and abbreviations

Acronyms are common and increasing over time, and many are not widely reused across fields. This creates comprehension problems. On citations, the evidence is not uniform. Some analyses find acronyms in titles are associated with lower citation rates, while other datasets report the opposite, likely reflecting field-specific acronym familiarity.

For title optimization, use a conservative rule that works across disciplines:

Avoid acronyms in the title unless they are widely recognized in your target audience (e.g., HIV, MRI).

If an acronym is necessary, consider spelling it out in the title and introducing the acronym in the abstract instead.

Never assume a general editor or interdisciplinary reviewer will decode a niche abbreviation on first pass.

A good final check for your title is to look for two signals:

Accuracy: your title matches what the paper actually does.

Economy: your title communicates the focus without redundancy, filler phrasing, or unnecessary complexity.

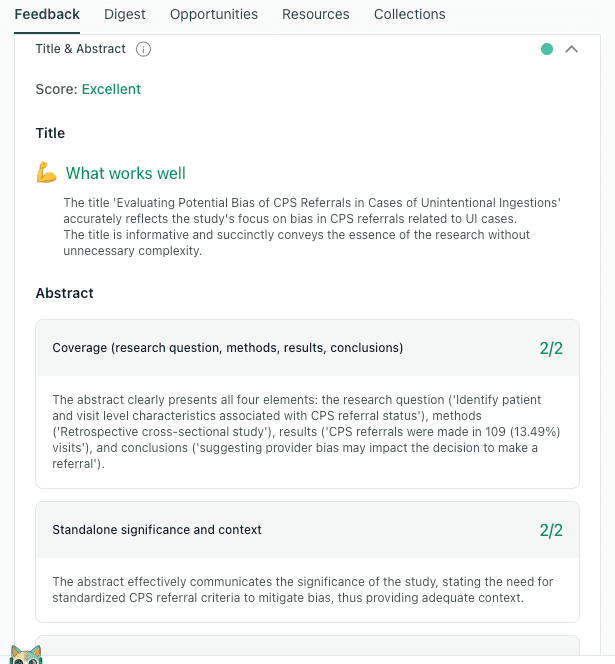

Example of title and abstract feedback reaching an Excellent score, with a brief explanation of what is working well.

If you are still getting feedback about your title’s redundancy, scope drift, or unclear focus, tighten the title before you spend time polishing the abstract.

At this point you have a concrete goal for your title: your first line should be readable to a smart non-specialist in your broader area, while still containing the terms that your actual readers search for. Next, you apply the same logic to the abstract, where structure and early keyword placement matter even more.

Writing an Abstract for Impact: Format and Flow

This section gives you a revision workflow for writing an abstract when you already have a full draft. You will learn how to choose the right format for your target venue, how to keep the logic tight (so an editor can screen it quickly), and how to write an opening line that signals relevance without wasting words.

If you need a fuller start-to-finish walkthrough on drafting from scratch, see How to Write an Abstract: Guide for PhD Students.

Structured vs. Unstructured Abstracts: Examples

Before you rewrite anything, check the author guidelines for your target journal or conference. Some venues require a structured abstract (with headings), others want a single paragraph, and many have strict word limits. Your job is to meet the venue’s expectations while still making your contribution easy to understand.

A useful rule is to treat structured and unstructured abstracts as two different presentation styles for the same content.

Structured abstracts make scanning easier because they label the logic for the reader (Background, Methods, Results). They are common in biomedical and clinical venues.

Unstructured abstracts can read more smoothly, but only if your sentences still follow a clear internal structure. Otherwise, they become a dense block of text that hides the result.

Below are structured abstract examples vs. unstructured versions of the same study. The content is intentionally generic so you can map it onto your own project.

Example A: Structured Abstract (with headings)

Background: Many studies report X, but evidence is inconsistent in Y context. Aim: We tested whether X is associated with Y in Z population. Methods: We conducted a [design] study using [dataset/sample], measuring [key variables]. We estimated [analysis approach] with [key controls]. Results: X was associated with Y (effect size, direction), and the association was stronger/weaker under [condition]. Conclusion: These findings suggest [bounded implication]. Future work should test [specific next step] in [specified setting].

Example B: Unstructured Abstract (single paragraph)

Prior evidence on X is mixed in Y context. This study examines whether X is associated with Y in Z population. Using a [design] and [dataset/sample], we measured [key variables] and estimated [analysis approach] with [key controls]. We found that X was associated with Y (direction, effect size), with stronger/weaker effects under [condition]. These results support [bounded implication] and suggest [specific next step] for research or practice.

What to notice in both versions:

The aim is explicit and arrives early.

Methods are condensed to what a reader needs to judge credibility, not every procedural detail.

Results include at least one concrete finding, not just a promise that results "will be discussed."

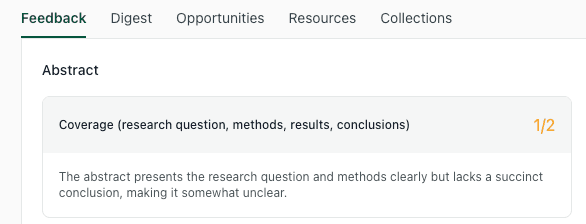

An "Excellent" rating in thesify indicates that all critical components—aim, methods, results, and conclusions—are effectively summarized.

The IMRaD Flow: Context, Gap, Methods, Results

Even when your abstract is unstructured, readers still expect a recognizable logic. The simplest pattern to follow is the IMRaD abstract flow. For a refresher on the broader paper structure, see How to Structure a Scientific Research Paper: IMRaD Format Guide.

For an IMRaD abstract, aim for four core moves. You do not need to label them with headings, but the sentences must still perform these functions:

1. Context (What is the topic?)

Your first one to two sentences should locate the paper in a specific problem space. Avoid writing a mini literature review. Instead, define the topic to help the reader classify your paper accurately (e.g., name the phenomenon, setting, or object of analysis).

2. Gap (What is missing?)

This is where many abstracts become vague. If your gap is not specific, your aim will feel generic. A strong gap sentence answers: “What do we not know yet, in what context, and according to which comparison?” (See Scientific Paper Introduction Structure: The Gap to Aim Link for how to build this logical bridge).

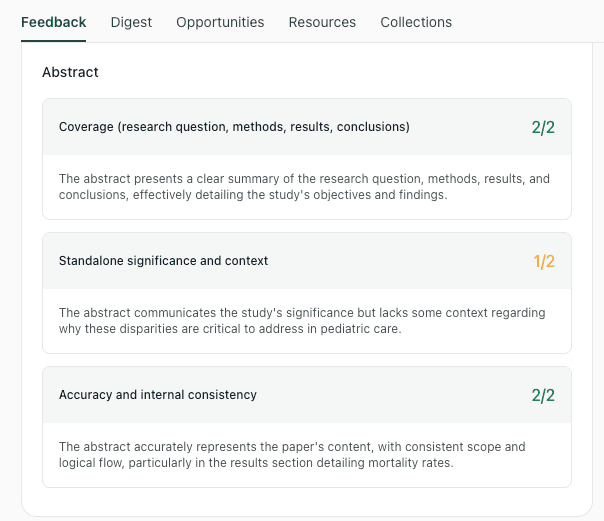

thesify breaks abstract feedback into coverage, standalone significance and context, and internal consistency, so you can revise the weakest dimension first.

3. Methods (How did you test it?)

Think of methods in the abstract as an editor’s credibility checkpoint. Include the design, data source/sample size, and analytic approach. You are not writing your Methods section; you are giving just enough information for a reader to judge if the evidence supports the claim.

4. Results (What did you find?)

This is the most common failure point in abstracts written under time pressure. Many abstracts describe what the paper “explores” without stating any result. A results sentence should include the direction of effect, magnitude, or boundary conditions. If you struggle to summarize your findings this concisely, check out tW: Do Your Results Fit 1 Line? to fix the flow.

A practical word budget:

Context: 1–2 sentences

Gap + Aim: 1 sentence

Methods: 1 sentence

Results: 1–2 sentences

Implication: 1 sentence

For a deeper dive on using "Claim, Context, Concepts, and Contribution" to organize these moves, read tW: Write Your Abstract - 4 Steps.

The “First Sentence” Test: How to Hook the Editor

An abstract hook in academic writing is a first sentence that makes the paper easy to classify and hard to dismiss.

A good first sentence passes two tests:

Relevance: A reader in your field can tell what the paper is about.

Specificity: The sentence contains at least one concrete term (phenomenon, population, setting, method) that distinguishes your study from adjacent papers.

Avoid openers that consume words without adding information:

“This paper is about…”

“In recent years, there has been growing interest in…”

“This study explores…”

These phrases postpone the actual topic and push searchable terms later, which hurts discoverability. Instead, use these opening patterns:

Topic + Context: “[Phenomenon] is [common/contested] in [specific setting], yet evidence on [specific relationship] remains limited.”

Problem + Consequence: “Unclear estimates of [X] in [Y context] limit [clinical decision-making/policy design/theory testing].”

Direct Aim (for specialized audiences): “We tested whether [X] predicts [Y] in [population], using [design] data from [source].”

A useful diagnostic is the deletion test. Remove your first sentence and read the abstract again. If nothing meaningful changes, and the abstract is only shorter, your opener is not doing enough work.

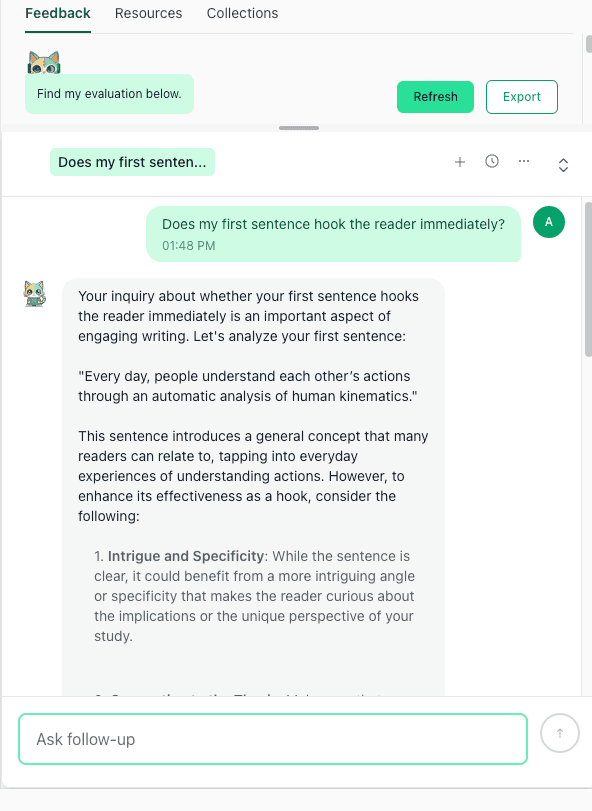

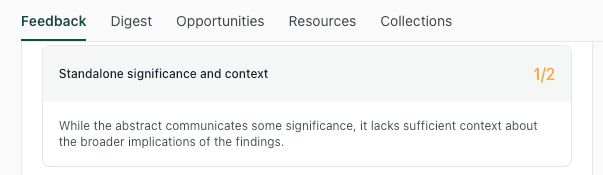

A fast way to pressure-test your opener is to use Chat with Theo to ask a single, narrow question and force a concrete diagnosis. If the feedback stays generic, the sentence is too generic. If the feedback points to a specific missing element, you have a clear revision target.

Example prompt to Chat with Theo to evaluate whether your abstract’s first sentence creates a clear hook.

When you revise, avoid generic openers like “This paper explores” or “In this study, we investigate.” Instead, spend your first sentence on information that makes the abstract scannable: what the phenomenon is, who or what you studied, and what makes the question non-trivial in this context.

Once the first sentence is doing real work, the rest of the abstract becomes easier to write because you have committed to a precise scope. To see exactly how titles and abstracts shape an editor's snap judgment, read tW: What Reviewers Notice First In Your Paper.

Keyword Strategy: Aligning Your Title and Abstract

At this stage, you have two separate drafts: a title that signals scope and an abstract that summarizes the study. Keyword strategy is the step where you make them behave like one coherent metadata unit.

The principle is simple: your title and abstract should use the same core vocabulary for the same concepts. If your title names a construct in one way and your abstract switches to synonyms, acronyms, or a more theoretical label, you create friction for both search and screening. Readers hesitate because they are not sure the paper they clicked is the one they wanted. Search tools hesitate because they have fewer consistent terms to match.

If you want a compact companion on framing your scope early, read tW: Let Your Title Do the Thinking to filter out detours before the reader invests time.

The “Golden Thread”: Matching Keywords Across Sections

Think of your main keyword set as a “golden thread” that runs through the first line of your title and the opening lines of your abstract. This is not a gimmick; it is a clarity constraint.

A workable workflow looks like this:

1. List your three term layers

Primary term: The one phrase that names the paper’s central topic, phenomenon, population, or method label.

Secondary terms: Two to four supporting terms that narrow the scope, such as setting, outcome, comparator, or method family.

Synonyms and variants: Common alternatives in your field, including spelling variants and standard abbreviations.

2. Check term consistency

The primary term should appear in the title in a direct form.

The same term should appear again in the first two sentences of the abstract, ideally in the same wording as the title.

Secondary terms should appear at least once in the abstract if they are central to the promise of the title.

If the first two sentences of your abstract do not contain the terms that classify the paper, you force the reader to work before they can decide whether the paper is relevant. You are also delaying the most searchable terms.

3. Make your first two abstract sentences do specific jobs You will usually get a cleaner result if you assign each sentence a function:

Sentence 1: Topic plus bounded context.

Sentence 2: Aim plus the key relationship you test.

Template:

“In [context], [primary term] is [known/contested], but evidence on [secondary term relationship] remains limited.”

“We tested whether [primary term] is associated with [outcome/comparator] in [population/setting] using [design].”

This alignment logic connects directly to Is Your RQ Type Right? because descriptive, comparative, explanatory, and predictive questions require different claims, and your keyword choices should reflect the question type, not just the topic label.

4. Run the mismatch audit Look for these common breakpoints and apply the fix:

Issue: Title uses "job insecurity," Abstract uses "precarious employment."

Fix: Use both, but introduce the synonym as a parenthetical, then stick to one label.

Issue: Title uses an acronym, Abstract uses the expansion (or vice versa).

Fix: Introduce the full term first in the abstract, then the acronym, then use one consistently.

Issue: Title uses a broad umbrella term, Abstract uses a narrow sub-term.

Fix: Decide which one is the true paper label and make the other a secondary term.

Natural Integration vs. Keyword Stuffing

Keyword stuffing is both an SEO problem and credibility problem. An abstract that repeats the same phrase mechanically signals that the author is writing for a system rather than for a scholarly reader.

The good news is that academic writing best practices already have built-in safeguards against stuffing. A well-structured abstract has distinct rhetorical jobs, and each job naturally introduces different terms.

Use these practices to keep keyword use natural:

1. Use one stable label for each concept

Pick a main label for the core construct and stick to it. Use synonyms sparingly, and only when you are clarifying meaning for interdisciplinary readers.

2. Prefer grammatical variation over lexical repetition

Instead of repeating the exact phrase, shift the sentence structure while keeping the concept stable.

“We tested the association between X and Y.”

“X was associated with Y.”

“The effect of X on Y was stronger in Z.”

The concept stays consistent, but the prose does not feel repetitive.

3. Do not force keywords into every sentence

A practical rule is that your primary term should appear in the title and early in the abstract, but it does not need to appear in every line. If your abstract is only 200 to 250 words, excessive repetition becomes obvious quickly.

4. Watch for readability flags

If you see any of the following, you are likely stuffing:

The same phrase appears twice in one sentence.

A keyword appears in places where it adds no meaning.

The abstract feels like it is “circling” rather than progressing.

A final check that works well is reading the abstract aloud once. If you can hear the repetition, your reader will feel it on the page.

For a companion checklist that reinforces this idea from a peer-review angle, read tW: What Reviewers Notice First In Your Paper.

The “Gap-Title” Alignment Audit: Testing Your Promise

Your title is a promise. Your abstract is the evidence packet that proves you can keep it.

Gap-Title misalignment happens when your title implies one kind of paper, but your abstract delivers another. This is not a stylistic issue; it affects three practical outcomes:

Editorial screening: An editor decides “fit” based on what you claim you did, not what you meant to do.

Search relevance: The wrong readers click, then bounce, because the abstract does not match the promise.

Trust: Reviewers become cautious when claims feel inflated or underspecified.

You can think of this as the same logic you use in an introduction, where the gap needs to support the aim. For a refresher on that logic, see Scientific Paper Introduction Structure: The Gap to Aim Link.

Gap-title alignment is a reliability test. Your title makes a promise about what the reader will learn, and your abstract must point to the exact evidence that supports that promise. When these two signals diverge, editors and reviewers often interpret it as overclaiming or unclear positioning.

Example thesify interface view showing title and abstract feedback alongside the draft, including suggested title revisions.

The Manual Check: Can You Point to the Sentence That Proves the Title?

Run this audit before you touch the wording. It is fast, and it prevents you from polishing language that is structurally mis-specified.

Step 1: Highlight the claim embedded in the title.

Underline the words that commit you to something specific. Most titles implicitly make one of these promises:

Descriptive promise: You map or characterize X in a defined context.

Comparative promise: You test whether X differs from Y.

Explanatory promise: You identify why X happens or what mechanism drives it.

Predictive promise: You model, forecast, or classify outcomes from predictors.

If you are unsure which promise your study can support, read tW: Is Your RQ Type Right?, as your question type determines what you can defensibly claim.

Step 2: Find the “evidence sentence” in the abstract.

Now look at the abstract and ask a strict question: If a skeptical reader demanded proof of the title’s promise, which single sentence in the abstract would you point to?

You should be able to underline one sentence that clearly does the job. Often it is a results sentence; sometimes it is a combined aim-plus-result sentence in very short abstracts. If you cannot underline a sentence, you have a mismatch.

Step 3: Check the verb alignment.

If your title uses causal or explanatory verbs (drives, leads to, explains, mechanism), but your results sentence only supports association or difference, revise the title first.

Step 4: Run the same audit faster in Chat with Theo.

Once you have done the manual underline test, you can run the same logic as a structured prompt in Chat with Theo. This is not for rewriting your paper. It is for catching overclaiming and for identifying exactly which sentence in the abstract carries the evidence. It is also a useful way to see, quickly, whether your title implies mechanism or causality that your results do not actually support.

Example Gap-Title Alignment Audit prompt in Chat with Theo, comparing the title’s implied claim to what the results sentence actually supports.

How to act on the output

Use the Chat with Theo audit result to choose the smallest safe revision:

If Theo flags overclaiming because your title implies mechanism or explanation, revise the title to match what you can defend from the results sentence (often the fastest fix).

If Theo flags missing evidence because your abstract does not contain a proof sentence, revise the abstract first by making the results sentence more specific (direction, magnitude, boundary condition).

If Theo flags a scope mismatch (population, setting, outcome), harmonize terminology across title and abstract before you polish style.

Common Gap-Title Mismatches and How to Fix Them

Most mismatches fall into a small set of patterns.

Mismatch 1: The title promises results, the abstract only promises exploration.

The tell: Title uses verbs like “improves,” “reduces,” “drives,” or “predicts.” Abstract says “we explore,” “we investigate,” or “we examine,” and never states a finding.

The fix: Either (a) add one concrete results sentence to the abstract, or (b) rewrite the title into a descriptive promise that matches what you actually report.

Resource: To ensure your findings are clear, see Scientific Paper Results Section Feedback: How to Audit Your Draft.

Mismatch 2: The title implies causality, the abstract describes association.

The tell: Title implies a mechanism (“X increases Y,” “X leads to Y”). Methods and results only justify correlation or are qualitative without causal identification.

The fix: Change the title to “association,” “relationship,” or “linked to,” or name the design explicitly if your field accepts it.

Resource: For help refining these limits, see Scientific Paper Discussion Section Feedback: How to Stress-Test Your Claims.

Mismatch 3: The title is narrow, the abstract is broad.

The tell: Title claims a specific population or setting. Abstract describes a general problem and never returns to the narrow scope.

The fix: Revise the first two abstract sentences so they restate the same scope terms that appear in the title (population, setting, timeframe, method family).

Mismatch 4: The title uses one label, the abstract uses another.

The tell: Title uses the term readers search for. Abstract replaces it with a synonym, acronym, or theoretical construct without mapping.

The fix: Introduce the alternate term as a synonym once, then use one stable label throughout the abstract.

Using thesify to Check Gap-Title Alignment Faster

You can do the manual audit in two minutes, but it is still easy to miss mismatch cues when you have been staring at the draft for weeks.

This is where thesify’s title and abstract feedback fits cleanly into the workflow. Instead of relying on self-evaluation, you run the same alignment test systematically:

Workspace example showing how thesify displays title and abstract feedback next to your draft.

Review the feedback for places where your title implies a stronger claim than your abstract supports.

Revise one variable at a time (scope term, claim verb, results sentence), then re-check.

Keep the goal narrow. You are checking whether your title’s promise is provable from the abstract as written, and whether the abstract’s evidence is easy to locate on a first pass.

The alignment audit ensures your abstract doesn't just sound good, but accurately represents the evidence contained in your results.

Word Count Limits and Journal Formatting Rules

When your title and abstract are strong, the fastest way to lose the benefit is to miss a technical requirement. Word count limits and formatting rules are not decorative. They are part of how editors triage submissions and how conference management systems validate your upload.

Typical Abstract Word Count Limits

Most venues set abstract word count limits somewhere in the 150 to 250 word range, but this varies significantly by article type and discipline. You will usually see different limits for original research versus reviews, and even tighter constraints for short communications or clinical trial reports.

A practical workflow is to treat the word limit as a design constraint, not a final edit.

Copy the exact limit from the author guidelines into your draft notes.

Identify whether the limit applies to the abstract text alone or includes keywords and titles.

Check whether the system counts headings in structured abstracts (e.g., "Background," "Methods").

If you routinely end up 20 to 50 words over, it is rarely because you need “tighter writing.” It is usually because your abstract is carrying too much background and not enough study-specific information. For specific cuts, see Quick Hacks to Increase or Decrease Word Count in Academic Writing.

Formatting Rules That Override Your Style

Even within the same field, abstract requirements differ across journals. Before you revise content, confirm the format the venue expects. These are the details that most often trip authors up:

1. Structured vs. Unstructured

Some journals require headings (Background, Methods, Results, Conclusion). Others forbid headings and demand a single paragraph. Submitting the wrong format signals you have not read the guidelines.

2. Required Content Items

Depending on the field, a venue may require explicit statements on:

Study design (e.g., "randomized trial," "cohort study").

Sample size or data source.

Registration numbers (common in clinical contexts).

3. Abbreviations and Citations

A common rule is “avoid abbreviations in the abstract unless they are widely recognized.” If you must use one, define it on first use. Similarly, many journals discourage or disallow citations in abstracts. If you find yourself wanting to cite, it is often a signal that your abstract is still doing literature review work rather than summarizing your specific study.

For a complete walkthrough of these pre-submission checks, see Submitting a Paper to an Academic Journal: A Practical Guide.

Formatting Specifics for APA and MLA

Confusion often arises because “APA” and “MLA” can refer to course paper formatting, thesis requirements, or a journal’s preferred style. In journal submissions, the journal’s author guidelines win.

APA: In APA-style manuscripts (common in psychology), the abstract is typically its own labeled section, written as a single paragraph. However, for journal submission, you must follow the journal’s specific format, even if the rest of your manuscript is in APA style.

MLA: In MLA-style writing (common in humanities), abstracts are not always required. When one is requested, follow the specific venue’s instructions rather than assuming a universal MLA format exists.

Remember: Your abstract is a logic summary, not just a formatting exercise. See How to Write a Scientific Paper in 2025: Ideas First.

How to Reduce Abstract Word Count Without Losing Meaning

If you are over the limit, do not start by deleting adjectives. Start by cutting the parts that are not carrying study-specific information.

Use this reduction order:

Compress background: Most abstracts need far less context than authors think. One sentence is usually enough to orient the reader.

Collapse Gap + Aim: If your gap is specific, you can often combine it with your aim into one compound sentence.

Cut procedural details: Keep design, data source, and analytic approach at a recognizable level. Remove step-by-step procedures that belong in the Methods section.

Replace “we explore” with results: Results sentences are often shorter than exploratory framing, and they do more work.

Remove duplicate phrases: Repeated topic labels are a common source of excess words, especially when you have already aligned keywords across the title and abstract.

Troubleshooting: Common Reasons for Abstract Rejection

Abstract “rejection” usually shows up as one of two outcomes:

A conference submission is screened out quickly.

A journal submission is desk-rejected because the editor cannot verify fit, contribution, or credibility.

In both cases, the pattern is the same: the abstract does not give a reviewer enough concrete information to justify reading the full paper.

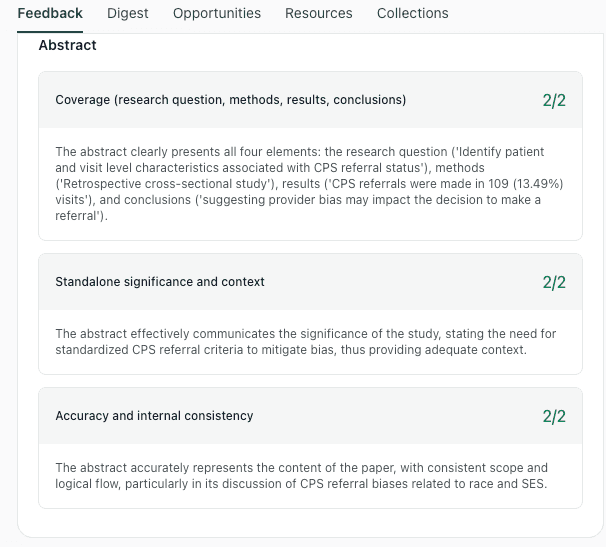

If you want a quick diagnostic that matches editorial behaviour, run a decidability check. The goal is simple: in 60 seconds, can a reader identify your method, your sample, and the direction of your results. If not, your abstract is not yet scannable.

Example of a decidability audit using Chat with Theo, flagging vague placeholder wording and missing method or sample details.

Diagnostic Checklist

Use the checklist below as a diagnostic. The point is to make your abstract decidable—meaning a reader can tell what you did, what you found, and what the paper adds.

1. Results are too vague

If your abstract identifies the research question but stops before the payoff, the audit will flag the missing conclusion.

Symptoms: Your results sentence uses placeholders like “significant,” “interesting,” “promising,” or “suggests,” without specifying what changed or in which direction. You describe what you did, but not what you found.

The Fix: Add one sentence that states the main finding in plain terms: direction, magnitude (if appropriate), and any key boundary condition.

Prompt: “We found that X was associated with Y (direction), and the effect was stronger/weaker in Z.”

Resource: Scientific Paper Results Section Feedback: How to Audit Your Draft.

2. Too much background, not enough study

Editors look for broader context; if your abstract is too narrow, use the significance audit to identify where you need to add "so what" framing.

Symptoms: The abstract reads like a miniature literature review. The aim appears late, or not at all. Methods and results are compressed into one vague final sentence.

The Fix: Cut background to one sentence. Combine your gap and aim into a single compound sentence. Reserve the word count for methods and results, as this allows the reader to judge whether your claim is supported.

Resource: Scientific Paper Introduction Structure: The Gap to Aim Link (useful for tightening the bridge between context and contribution).

3. The aim is unclear or underspecified

Symptoms: The abstract says “this paper explores” without naming the relationship, comparison, or mechanism you test. Your reader cannot tell whether the paper is descriptive, comparative, explanatory, or predictive.

The Fix: Rewrite the aim as a testable statement. Even in qualitative work, you can name what you are explaining, comparing, or characterizing. If your question type is ambiguous, your title and abstract will drift.

Resource: How to Identify Research Gap for Novelty: A Step-by-Step Guide.

4. Methods are missing or not credible at a glance

Symptoms: You do not name the design, the data source, or the analytic approach. The methods sentence is so technical that a general editor cannot parse it.

The Fix: Include one clean methods line with: design, sample/data source, and analysis type. Keep it recognizable rather than exhaustive.

Resource: Methods Section Feedback in thesify (for more information on the “one clean line” approach).

5. Overclaiming beyond what the design supports

Symptoms: The abstract implies causality without a causal design. The conclusion reads like a general law rather than a bounded finding.

The Fix: Replace causal verbs (“drives,” “leads to”) with design-appropriate language (“is associated with,” “is linked to,” “we observed”). Add a constraint phrase when needed (population, setting, timeframe).

Resource: Scientific Paper Discussion Section Feedback: How to Stress-Test Your Claims.

6. Undefined acronyms and dense jargon

Symptoms: Acronyms appear in the first lines with no definition. Key terms are field-internal shorthand rather than the language readers search for.

The Fix: Spell out the term on first use, then introduce the acronym in parentheses if you must use it later. Replace localized jargon with the standard term used in your target journals.

7. Title–Abstract mismatch

Symptoms: Your title promises one thing (comparison, mechanism, prediction), but the abstract delivers another (description, exploration). Your title uses one core term, but the abstract switches labels or synonyms.

The Fix: Run the Gap-Title Alignment Audit: Underline the claim in the title, then underline the sentence in the abstract that proves it. If you cannot find the “evidence sentence,” revise either the title promise or the results line.

Resource: Scientific Paper Introduction Structure: The Gap to Aim Link.

8. Format noncompliance

Symptoms: Over the word limit. Wrong format (e.g., structured headings required but missing). Keywords omitted or placed in the wrong field.

The Fix: Treat the author guidelines as the governing document. Adjust format first, then revise content inside that structure.

Resource: Submitting a Paper to an Academic Journal: A Practical Guide.

A Fast Repair Loop You Can Reuse

If you want a repeatable workflow, do this in order:

Write the aim in one sentence.

Write the main result in one sentence.

Write the methods in one sentence.

Add one context sentence at the top.

Add one bounded implication at the end.

Then check: does your abstract read as one coherent argument, or does it feel like five disconnected lines? If it is disconnected, the usual fix is to tighten your aim sentence so it logically predicts the result sentence.

Conclusion: Your Pre-Submission Optimization Checklist

If you are close to submission, you need a reliable pre-flight check you can run in a few minutes, every time, to confirm that your title and abstract are discoverable, readable, and defensible.

Use the checklist below as your final pass for research paper title and abstract optimization.

Pre-Flight Checklist: Title

Front-load the main term. Your primary concept (phenomenon, population, method label, or condition) appears in the first 10 to 12 words.

Make the promise clear. The title signals what kind of paper this is (descriptive, comparative, explanatory, predictive) without implying claims you do not test. (See Scientific Paper Introduction Structure: The Gap to Aim Link to verify your promise).

Keep scope terms stable. Population, setting, timeframe, and key outcome terms match how you describe them in the abstract.

Remove jargon and acronyms. No unexplained abbreviations. If an acronym is unavoidable, ensure the title remains readable without it.

Use a colon only when it adds clarity. The subtitle should add context or constraints, not restate the title in different words.

Pre-Flight Checklist: Abstract

First sentence does real work. It names the topic and a bounded context, without empty framing (e.g., “This paper explores…”).

Aim is explicit and testable. The abstract states what you set out to determine, compare, explain, or predict. (See How to Write an Abstract: Guide for PhD Students).

Methods are credible at a glance. One clean line includes design, data source or sample, and analysis type. (See Methods Section Feedback in thesify).

Results are concrete. At least one sentence states a main finding, including direction and any key boundary condition. (See Scientific Paper Results Section Feedback: How to Audit Your Draft).

Implication stays bounded. The last sentence explains what the result means without inflating it beyond what your design supports.

Format matches the venue. You meet the word limit and follow structured vs. unstructured requirements.

Example abstract scorecard in thesify, showing how feedback is organized across key criteria.

Pre-Flight Checklist: Keyword Alignment

Golden thread is intact. The primary term from the title appears again in the first two sentences of the abstract.

Secondary terms are present. Key scope terms in the title also appear at least once in the abstract.

No keyword stuffing. You use one stable label per concept, and repetition is driven by meaning, not by forcing phrases.

No label switching. If you introduce a synonym, map it once, then keep terminology consistent. (For quick reinforcement, read tW: Let Your Title Do the Thinking).

Don’t audit manually. Paste your title and abstract into thesify for an instant optimization report.

The manual checklist works, but it is easy to miss small mismatches when you are tired or close to a deadline. If you want a faster workflow, run thesify’s title and abstract feedback and treat it as a structured revision loop:

Paste in your title and abstract.

Review where wording is vague, inflated, or misaligned.

Revise one variable at a time (scope term, claim verb, results sentence).

Re-check before you submit.

If you are already using thesify for section-level feedback, you can connect this step to your broader pre-submission process using How to Use thesify’s Downloadable Feedback Report and Introducing In-Depth Methods, Results, and Discussion Feedback.

Stop Guessing—Get Instant Title & Abstract Feedback for Free

Sign up for thesify for free. If you want structured feedback on scope, keyword placement, and title–abstract alignment, paste your title and abstract into thesify and use the comments as a revision checklist before submission.

Related Resources

How to Write an Abstract: PhD Student Guide: Know your abstract’s job.Your abstract should let a time-pressed reader answer four questions quickly: What is the problem, what did you do, what did you find, and why does it matter. Keep it self-contained, avoid citations and undefined acronyms, and match the venue’s length and structure rules. Learn how to write a clear, publishable abstract for dissertations, journal articles, and conferences. See three real case studies with thesify feedback and quick fixes.

Scientific Paper Introduction Structure: The Gap to Aim Link: In this post, you will apply a practical method for building that chain using the CARS moves and the funnel, then run targeted checks for gap–aim alignment, problem significance, and literature positioning. You will also see how thesify’s Introduction section feedback can surface weak links during revision, before you move on to the Discussion, where you later interpret what your results mean and why they matter.

How to Submit a Paper to a Journal: Step-by-Step: This guide walks you through a practical step-by-step process you can reuse for future submissions and how to choose a journal your paper actually fits. You will learn how to shortlist journals, prepare every file the submission system expects, write a cover letter that supports editorial screening, and understand what happens after you submit.