Scientific Paper Introduction Structure: The Gap to Aim Link

Your scientific paper introduction structure should make your rationale explicit. In a research paper introduction, you justify the study by linking three elements in sequence:

What is known

What is missing (the research gap)

An aim that directly addresses that gap

When the gap does not logically require the aim, the opening reads as topic description rather than a defensible argument for why the study was needed.

To fix this, you need a practical method for building that logical chain—using the CARS model and the 'funnel' approach—followed by targeted checks for gap–aim alignment, problem significance, and literature positioning. You will also see how thesify’s Introduction section feedback can surface weak links during revision, before you move on to the Discussion, where you later interpret what your results mean and why they matter (see Discussion Section Feedback for further advice).

Related Resource: If you're new to academic writing, check out our Step-by-Step Academic Writing Guide.

What the Introduction Must Justify (Rationale, Not Background)

The primary purpose of an introduction in a research paper is to establish a clear rationale. Editors and reviewers look for a specific intellectual argument: a logical demonstration that the current study is necessary to resolve a gap or problem in the existing knowledge. If the text functions only as a history lesson without establishing why new inquiry is needed, it fails its primary function.

A helpful distinction is to contrast the core function of the Introduction with other sections:

Introduction: Justifies the study

Why does this question exist?

Why is it necessary now?

Results: Reports findings

What did you observe?

What are the data?

If you struggle to summarize your findings clearly, read Do Your Results Fit 1 Line? to fix your flow.

The CARS Model (Creating a Research Space)

A practical way to structure this justification is the CARS model research framework (Swales, 1990), which describes three rhetorical moves that take the reader from context to a specific research aim using three distinct "moves."

Using the CARS model helps your opening follow a logical progression:

1. Establish Territory: Show that the general research area is important, central, or problematic (what is known and why it matters).

2. Establish Niche: Indicate a gap in the previous research, raising a specific question or highlighting a contradiction (what is missing or contested).

3. Occupy Niche: State the nature of the present research and outline the specific research aim (what your study will do).

Introduction vs Literature Review: What Belongs Where

Confusion about introduction vs literature review usually comes from treating both sections as “the place where you cite sources.” The difference is not whether you cite, it is why you cite.

A research paper introduction uses literature selectively to set up a specific problem and justify the gap your study addresses. A literature review, by contrast, uses literature systematically to map what the field has established, where it disagrees, how ideas and methods developed, and what patterns or limitations emerge across bodies of work.

Use this rule while drafting: the introduction should only include literature that you actively need to reach your gap and aim, while the literature review includes literature you need to understand and evaluate the landscape in full. If you find yourself summarising study after study without moving the argument forward, you have started writing a literature review inside your introduction.

Related Resource: Need strategies for structuring your literature review? See our expert guide on how to write a literature review.

Belongs in the introduction

A small set of citations that establish the territory (what the problem is, why it matters, what is already accepted).

Evidence of a specific limitation, inconsistency, or unanswered question that supports the research gap you will name.

A short synthesis that positions your study in relation to prior work, for example, “most studies assume X,” “the evidence is limited to Y,” or “findings diverge on Z.”

Only enough detail to make your gap credible and your aim necessary.

Belongs in the literature review

A comprehensive, structured map of the relevant scholarship, grouped by theme, debate, theoretical approach, method, or chronology.

Evaluation of bodies of work (strengths, limitations, typical designs, measurement choices, bias risks, and where evidence is strongest or weakest).

A synthesis that shows how the field developed and where the major lines of argument sit, including competing explanations and unresolved tensions.

The fuller context needed to motivate hypotheses, conceptual models, or a detailed methodological choice.

If you are writing a paper with a distinct literature review chapter or section, keep your introduction lean and argumentative, then expand the field mapping later. For a step-by-step approach to structuring that longer synthesis, see the Step-by-Step Literature Review Guide.

How to Structure a Research Paper Introduction (The Funnel)

The standard structure of scientific paper introduction writing follows a "funnel" shape: it begins with the broad context and systematically narrows down to the specific problem your study addresses. This logical progression ensures the reader understands the territory before being introduced to the specific niche you intend to occupy.

Example of thesify flagging structure and flow issues, usually caused by abrupt transitions from context to aim.

Here is the four-step sequence to build a robust research paper introduction structure:

1) Build a Contextual Foundation Without Fluff

You must define the territory, but avoid the textbook trap. Do not explain concepts your target audience already knows. The goal is to provide just enough background information in research context to make the problem understandable and to set up the gap and aim you will claim next. You can often start this framing before you even write the first sentence—read Let Your Title Do the Thinking to filter out detours early.

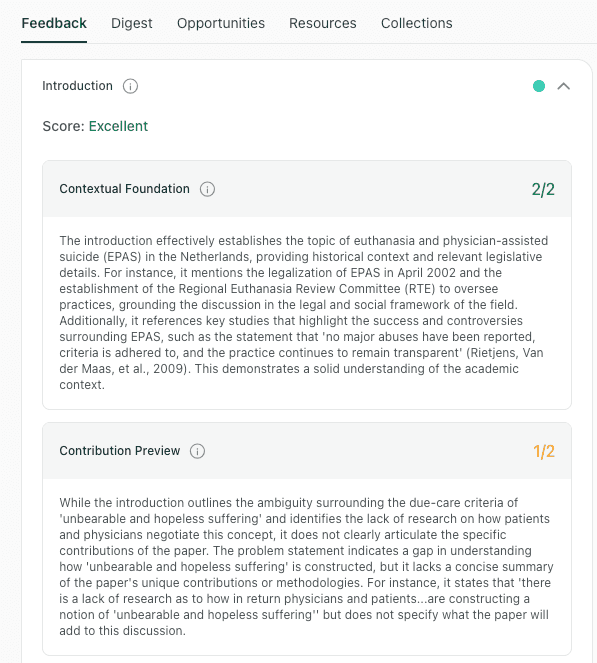

thesify’s Contextual Foundation rubric checks whether your introduction section has established that ground effectively, and whether the context you included is doing real work for the argument.

Example of thesify’s section-level Introduction feedback highlighting Contextual Foundation and related checks.

Too Broad (Textbook):

“Euthanasia is a controversial topic in many countries.”

Your reader already knows this and it does not set up your specific problem.

Focused (Contextual):

“In the Netherlands, euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide are regulated under the Termination of Life on Request and Assisted Suicide Act (2002), with Regional Euthanasia Review Committees (RTE) assessing whether physicians met the due care criteria.”

This establishes the institutional and legal context that your argument depends on.

2) Identify the Research Gap (Types and Wording)

This is the pivot point of the funnel. You must explicitly state what is missing in the current literature. How to find a research gap depends on your field, but most gaps fall into these specific types of research gaps:

Evidence gap: "While X is known, data on population Y is missing."

Methodology gap: "Previous studies relied on self-report, limiting objective measurement."

Theory/mechanism gap: "We know X correlates with Y, but the underlying mechanism remains unclear."

Contradiction gap: "Recent findings regarding X have been inconsistent."

Temporal gap: "Most evidence is cross-sectional, so temporal ordering is unclear."

Research Gap Sentence Stems:

"However, few studies have investigated..."

"Despite these advances, it remains unclear whether..."

"To date, no study has examined..."

3) State the Research Aim (and Objectives)

Once the gap is defined, you must state how you will fill it. This is your purpose statement. Write it so the reader can see, without inference, how the aim follows from the gap you have just stated.

Be careful to distinguish between:

Aim: The broad, single-sentence goal (e.g., "To investigate the relationship between...").

Objectives: The operational steps (e.g., "1. To measure X; 2. To compare Y").

Hypothesis: The predicted outcome (e.g., "We hypothesized that X would increase Y").

In thesify, Introduction section feedback highlights whether your aim is specific, actionable, and explicitly linked to the gap you have established.

Example Flow:

Gap: "There is a lack of consensus on the role of motor representations in action comprehension (Direct-Matching vs. Action-Understanding theories)."

Aim: "To investigate whether individuals with cerebral palsy (who have atypical motor control) experience difficulties in action perception."

Objective: "To compare action recognition accuracy between participants with cerebral palsy and a control group."

4) Write the Last Paragraph of the Introduction

The last paragraph of your introduction is the most standardized part of your paper. It serves as the final roadmap before the Methods section.

What to include in the last paragraph of an introduction typically follows this formula:

Aim: Re-state what you set out to do.

Approach: Briefly mention the methodology.

Contribution preview: State what the paper adds (not just what it discusses).

Paper roadmap (optional, field-dependent): Signal how the paper is organised.

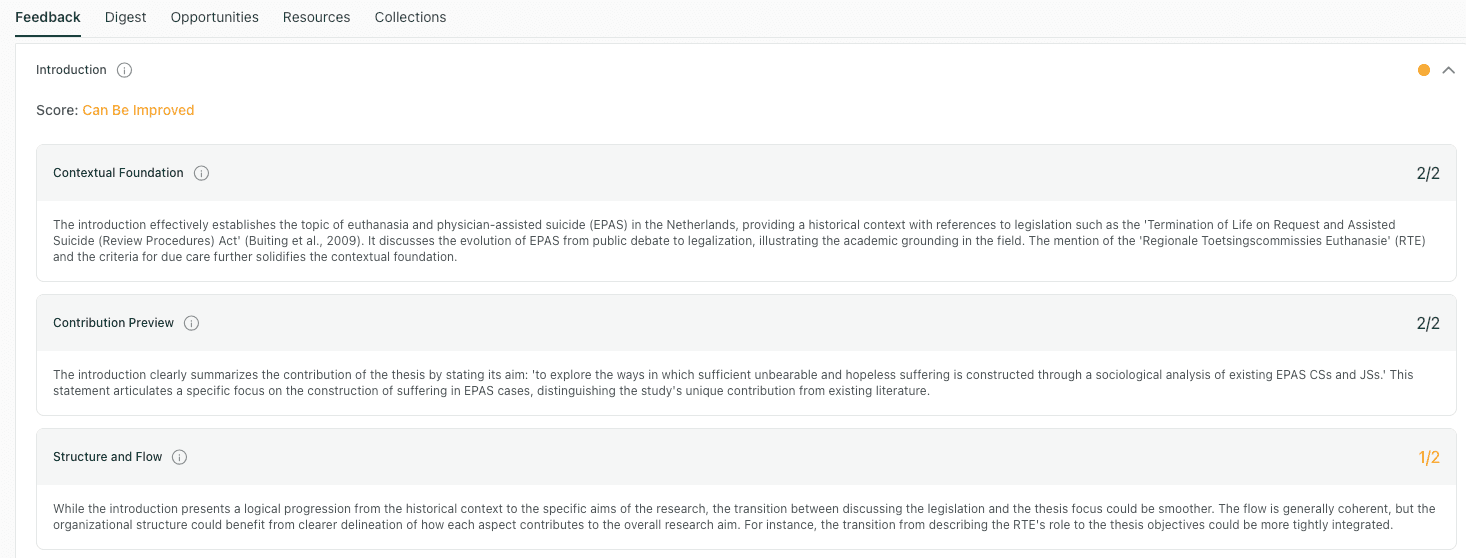

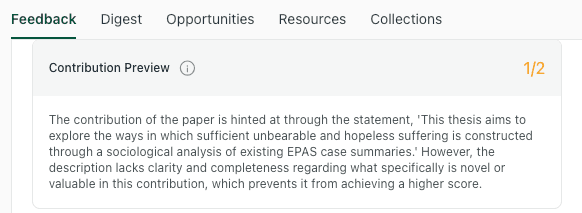

Example of thesify’s Introduction feedback showing that a strong contextual foundation can still score lower on Contribution Preview, which is often fixed by tightening the final paragraph.

Examples (adapt to your field and design):

Aim: “This study examines…” / “This paper investigates…”

Approach: “Using a longitudinal cohort design…” / “Using a qualitative interview study…”

Contribution preview: “This study clarifies…” / “This paper provides evidence on…” / “This analysis resolves…”

Paper roadmap: “The paper proceeds as follows…”

The Gap-Aim Alignment Check (Avoid the Gap-Trap)

Gap–aim alignment is the simplest way to test whether your introduction is doing its job. If your research gap describes what is missing, your research aim must state what you will do that directly resolves that missing piece.

When this link is weak, you usually see the same symptom in reviewer feedback: the problem statement is clear enough to follow, but the proposed aim feels adjacent rather than necessary. That is a problem statement consistency issue, and it is one of the most common reasons an introduction reads as unconvincing even when the topic is interesting.

Do the check mechanically. Identify your gap sentence and your aim sentence. Strip each down to the core claim. Then ask: if the gap is true, would the aim plausibly change what the gap points to, or does it merely add another description of the same space? If the aim does not “solve” the gap at the level of design, population, mechanism, or comparison, you have a gap-trap.

Wrong vs Right: Does the aim actually address the gap?

Research gap (what is missing) | Wrong aim (does not resolve the gap) | Right aim (directly resolves the gap) |

"Most evidence is cross-sectional, so temporal ordering is unclear." | "We describe attitudes at one time point." | "We test temporal ordering using longitudinal data." |

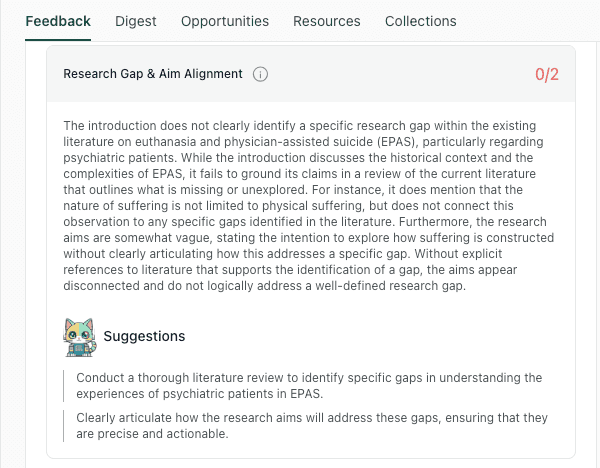

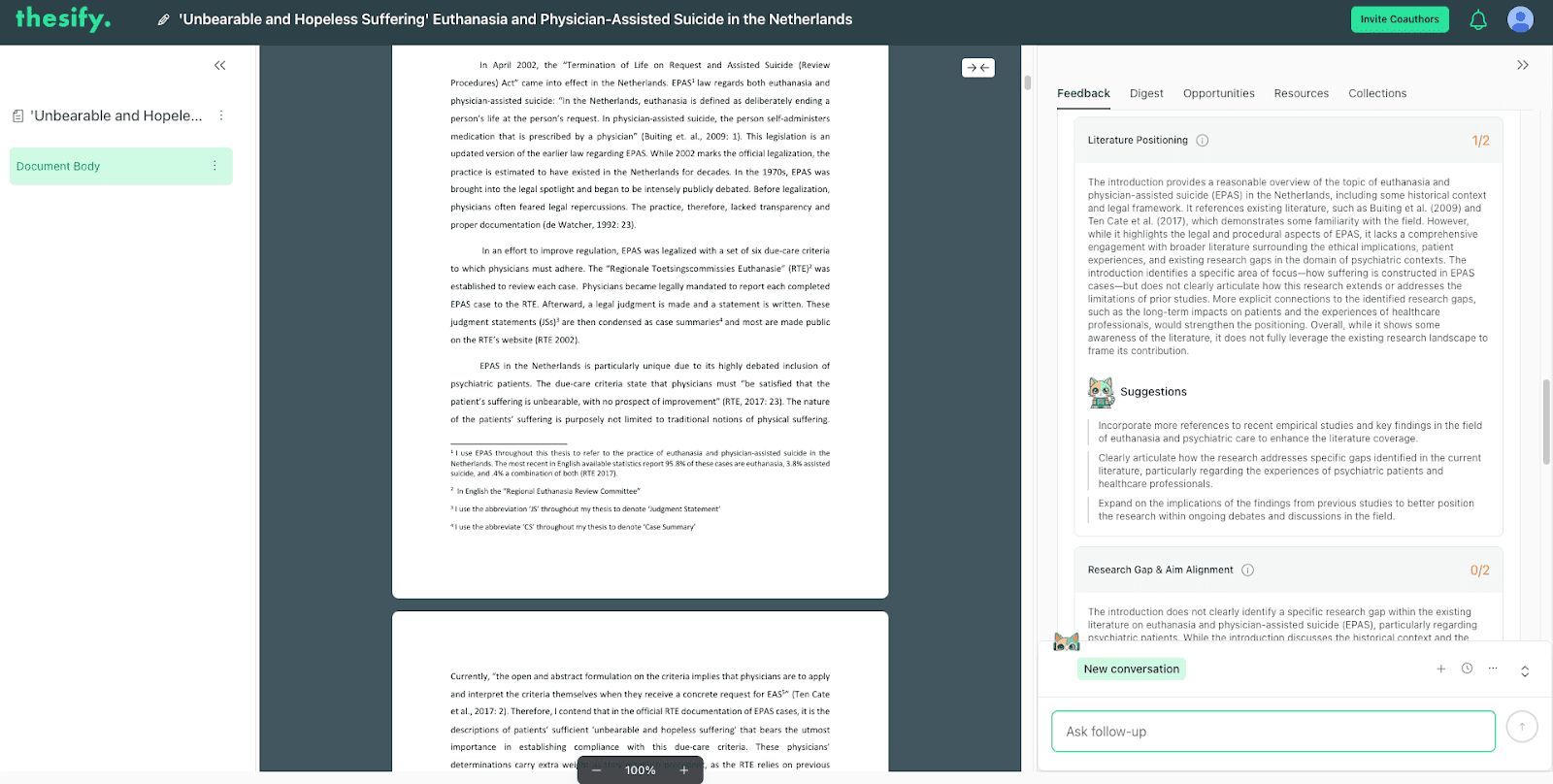

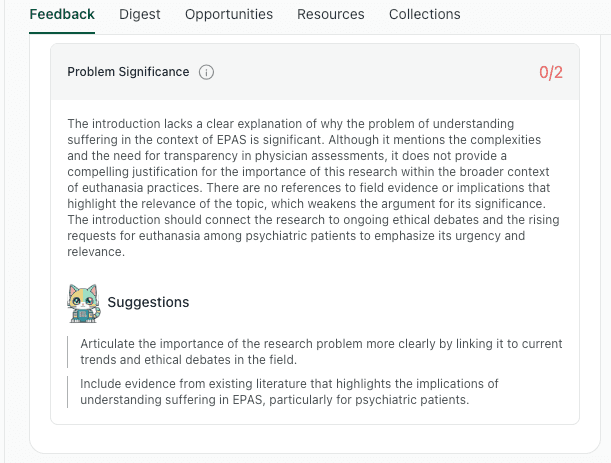

Example of thesify’s Introduction section-level feedback flagging weak gap–aim alignment (0/2) and outlining how to make the gap and aims precise and connected.

How to use this table when revising:

If your gap names a missing type of evidence (longitudinal, causal, comparative), your aim must name the corresponding evidence strategy.

If your gap is about who has been studied, your aim must specify the population and show that studying them changes the claim.

If your gap is about why or how something happens, your aim must target mechanism, not description.

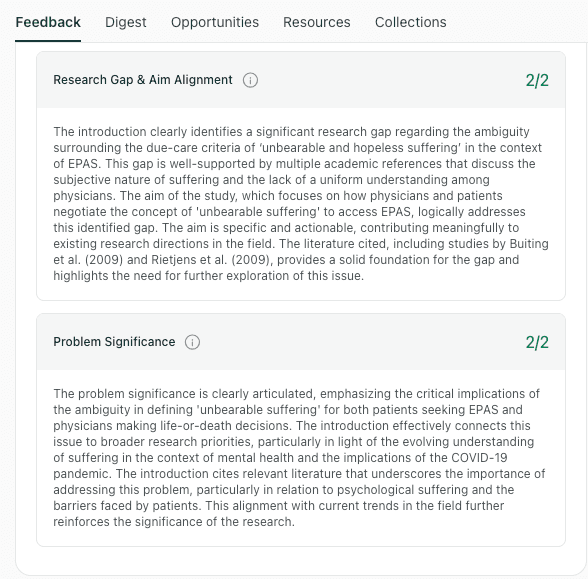

Example of thesify’s Introduction section-level feedback showing strong Research Gap & Aim Alignment (2/2) and Problem Significance (2/2), with notes linking the gap, aim, and stakes.

In thesify, the Research Gap & Aim Alignment dimension applies this logic check directly to your introduction section. It is not scoring whether you included a gap sentence and an aim sentence. It is scoring whether the aim is the logical response to the gap you have stated, and whether that relationship is explicit enough that a reader does not need to infer the link.

Common Misalignment Patterns (and How to Fix Them)

Below are frequent “research aim doesn’t match gap” cases, written as a diagnostic you can apply while you draft.

1. The Mechanism Gap vs. Descriptive Aim

Symptom: You claim a mechanism gap (how or why something happens), but your aim is descriptive (“we examine levels/associations/trends”).

Why it fails: A descriptive design cannot answer a mechanism claim, so the introduction overpromises relative to what the study can deliver.

Quick fix: Either narrow the gap to a descriptive uncertainty (“the distribution/pattern is not well characterised”) or strengthen the aim to match a mechanism test (methods, design logic, or analytic strategy that can speak to mechanism).

2. The Population Gap vs. Generic Aim

Symptom: You claim a population gap (“under-studied group”), but your aim is generic (“we investigate X”) with no population specification.

Why it fails: The reader cannot see what new evidence will be produced regarding that specific group.

Quick fix: Move the population into the aim sentence and make the novelty explicit (“in [population/context], where evidence is limited”).

3. The Contradiction Gap vs. Ignoring the Conflict

Symptom: You claim a contradiction gap (studies disagree), but your aim does not address the source of disagreement.

Why it fails: Simply adding another study rarely resolves a contradiction unless the aim is designed to adjudicate between explanations.

Quick fix: Rewrite the aim as an adjudication aim (“we test whether X vs Y explains the discrepancy”).

4. The Urgent Gap vs. Minimal Aim

Symptom: Your gap is expansive and urgent, but your aim is too small to justify the rhetoric (overclaimed gap → minimal aim).

Why it fails: The introduction asks the reader to accept a high-stakes problem, then offers a modest contribution that does not match the framing.

Quick fix: Either scale down the gap language to match what the study can credibly contribute, or make the aim explicit about scope (“we provide an initial test/pilot/feasibility study”) and state the contribution at the appropriate level.

If you apply these checks before polishing style, you prevent downstream problems. A well-written introduction cannot compensate for weak gap–aim alignment. The logic has to hold first, then you can refine clarity, emphasis, and flow.

Problem Significance: Passing the “So What?” Test

In a strong introduction, the significance of the study is an inference the reader can verify from your own setup. You establish it by showing what remains uncertain because the gap exists, and what becomes possible to claim, explain, or decide once your aim is met.

Write this as a short argument, not as a label (“important,” “timely,” “novel”) that you expect the reader to accept on trust. For more on keeping your reader engaged with the 'So What?' factor, read What Every Strong Paper Has in Common.

Use a concrete test while drafting. After your gap sentence and aim sentence, add two sentences that do the following:

State the consequence of the gap in the scholarly or applied context (what cannot be concluded, predicted, compared, or decided).

State what your study will change at the level your design can support (what will be clarified, constrained, or tested), and for whom or under what conditions.

Then choose one primary justification route and write it in specific terms.

Theoretical justification:

Specify the concept, relationship, or mechanism that remains underspecified because of the gap.

State what your study will allow the field to interpret differently, or what competing explanation it can constrain.

Avoid vague claims about “advancing knowledge,” name the exact interpretive problem.

Clinical or public impact justification:

Identify a concrete decision point, practice, or risk where current evidence is insufficient.

State the uncertainty your study reduces, and define the population or setting to which that reduction applies.

Policy justification:

Identify the policy claim, guideline assumption, or resource allocation that currently relies on incomplete or inconsistent evidence.

State what your study can reasonably inform, and keep the scope bounded to what your design can support.

Methodological justification:

Specify what is limiting in current measures, designs, or analytic strategies, then state what your approach contributes (validity, comparability, robustness, replication value).

This works well when the gap is driven by measurement inconsistency or design constraints across studies.

In thesify, the Problem Significance rubric focuses on whether your significance claim is anchored to the gap and aim you have actually stated in your introduction, and whether the stakes you describe are proportionate to the evidence your study can provide.

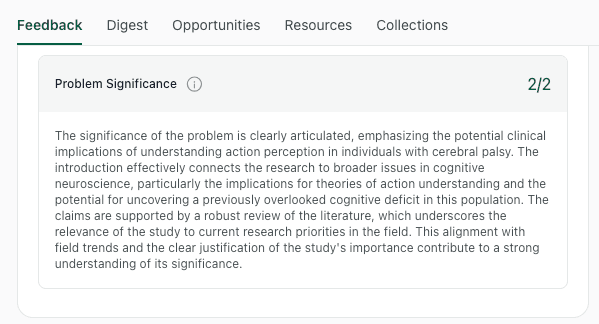

thesify confirms when your significance statement is clearly articulated and effectively connects your research to broader issues or clinical implications.

Academic vs Practical Significance

Academic significance is the contribution your study makes to scholarly explanation or interpretation, for example, clarifying a contested relationship, testing a mechanism, or narrowing uncertainty around a theoretical claim.

Practical significance is the contribution your study makes to action or decision-making, for example, informing clinical timing, programme design, policy assumptions, or identifying where evidence is too weak to justify intervention.

Example of thesify’s Introduction feedback showing strong Contextual Foundation and Contribution Preview, which support a defensible significance claim.

One project can justify both when you keep the claims aligned to scope. For example, if your research gap concerns uncertainty about a mechanism or interpretation, and your research aim tests that uncertainty using a design or population that directly challenges the field’s usual assumptions, the academic significance is that the literature can interpret prior findings with fewer unsupported inferences. The practical significance is that decisions about assessment, intervention, or policy can be better calibrated to what your evidence actually shows, within the population, setting, and tasks you studied.

Literature Positioning in the Introduction (Argument, Not Citation Dump)

A common mistake in literature review in introduction sections is citation dumping, listing author after author without building a coherent narrative. Reviewers do not only want evidence that you have read the field, they want to see how you organise it to justify your specific question.

The practical standard is simple: your citations should do argumentative work. They should establish what is known, clarify what is contested, and make the research gap read as the next logical step.

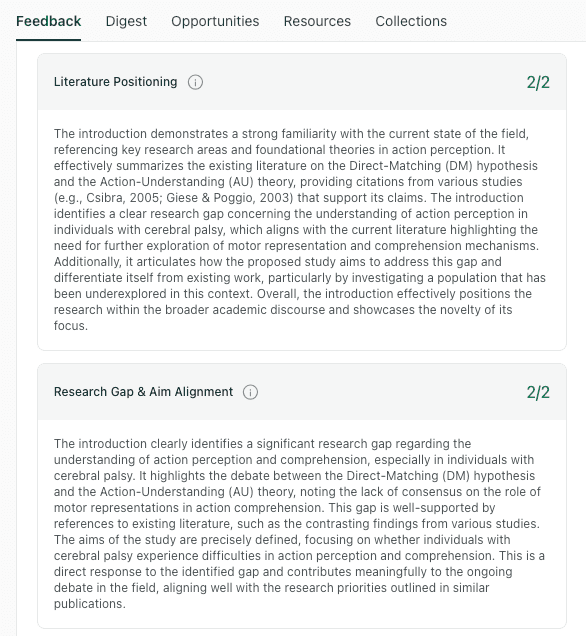

Example of thesify’s section-level Introduction feedback showing strong Literature Positioning (2/2) alongside Structure and Flow notes (1/2) about smoothing transitions and clarifying how each element supports the aim.

Effective literature positioning moves beyond "Who said What" to "What is Known vs. What is Contested." To transform a summary into an argument, you must synthesize previous work by:

Grouping by Theme: Organize citations by debate, mechanism, or methodology rather than by author.

Identifying Tensions: Explicitly state what is established and what remains contested or unknown.

Making the gap unavoidable: Use the literature to show why the unresolved point you identify is the next logical step for the field.

thesify’s Literature Positioning rubric evaluates this move directly. It distinguishes between introductions that demonstrate familiarity with the field and introductions that clearly articulate how the present study extends, tests, or addresses the limitations of prior work.

thesify’s Literature Positioning feedback highlights effective synthesis, confirming when an introduction moves beyond simple citation to clearly frame the study's contribution within existing research.

Moving From “Who Said What” to Synthesis by Theme

A powerful switch you can make is changing the subject of your sentences from authors to ideas.

thesify evaluates whether you are positioning your research within ongoing debates—like the ethical implications of psychiatric euthanasia—or merely listing citations without synthesis.

Before (Citation Dump):

"Buiting et al. (2009) studied the Euthanasia Act in the Netherlands. Ten Cate et al. (2017) also looked at due-care criteria. De Wachter (1992) discussed legal repercussions for physicians."

Why this version fails: It lists studies without explaining how they relate to your specific gap.

After (Synthesis):

"While the legal framework for euthanasia in the Netherlands is well-documented (Buiting et al., 2009), the application of due-care criteria to psychiatric patients remains contested (Ten Cate et al., 2017). Specifically, previous studies have not fully addressed how the subjective nature of 'unbearable suffering' complicates legal compliance for physicians (De Wachter, 1992)."

Why this version works: This is an argument. It uses citations to establish a contested point and justify the gap your study addresses.

Introduction Section Checklist (Reviewer-Style Audit)

Before you submit, run your draft through this introduction checklist. These are the specific dimensions thesify evaluates to perform a scientific writing audit on your manuscript, ensuring you have met the structural expectations of peer reviewers.

Example of thesify’s Introduction section-level feedback view, showing how scores and comments sit alongside the manuscript for fast revision.

Contextual Foundation:

Is the background focused and necessary?

Have you defined key terms without turning the opening into a generic textbook summary?

Research Gap:

Is the missing piece (evidence, method, theory) explicit and specific?

Have you grounded this gap in existing literature rather than just asserting it exists?

Aim Alignment:

Does your stated research aim directly resolve that specific gap? (Avoid mismatching a mechanistic gap with a descriptive aim).

Problem Significance:

Is the “so what” justified, not just asserted?

Have you explained why this problem matters for clinical practice, policy, or theory?

Example of thesify’s Introduction feedback flagging weak Problem Significance (0/2) and providing revision suggestions.

Literature Positioning:

Does the literature build an argument, not just a list?

Have you synthesized findings to show where the field stands and where the conflict lies?

Last Paragraph:

Are the aim, approach, and contribution preview clear?

Does the reader know exactly what this paper achieves by the end of the section?

Example of thesify flagging a weak Contribution Preview (1/2), a common last-paragraph issue when the paper’s “what this adds” is not stated directly.

FAQs: Common Questions About Introduction Structure

How long should a scientific paper introduction be?

There is no fixed length that applies across fields, but the constraint is functional: the introduction should be long enough to (1) establish the problem space, (2) make the gap credible, and (3) state an aim that follows from that gap, without drifting into a full literature review. As a practical drafting rule, aim for a small number of paragraphs that accomplish those moves cleanly, then cut anything that does not directly support the gap–aim link. If you cannot point to the sentence that states the gap and the sentence that states the aim, your issue is structure, not length.

Do you cite sources in the introduction?

Yes. You cite in the introduction to do three things: establish what is already accepted, justify the gap by showing what evidence is missing or inconsistent, and position your study in relation to prior work. Keep citations selective and strategic.

If the introduction becomes a sequence of study summaries, you have shifted into literature review territory. Prioritise sources that define core concepts, represent the dominant evidence base, and support the specific limitation you are claiming.

What is the difference between a research aim and an objective?

A research aim states the overall purpose of the study in one sentence, it answers “what will this paper do in response to the gap?” Objectives break that aim into a small set of concrete steps, they answer “what do you need to do to achieve the aim?”

In most papers, the aim is singular and the objectives are 2–4 items that specify actions such as estimating an effect, comparing groups, testing a mechanism, validating a measure, or evaluating an intervention. If your objectives introduce work that does not directly serve the aim, you have a coherence problem.

How specific should a research gap be?

Specific enough that a reader can tell what evidence would count as “filling” it. A useful gap names the dimension that is missing or uncertain, for example population, setting, method, mechanism, comparison, or timeframe. Avoid gaps that are only topic-level (“little is known about X”) unless you immediately specify what, exactly, is unknown about X. If you cannot draft an aim that directlimy resolves your gap, the gap is almost always too vague or too expansive.

Can you include results in the introduction?

In most cases, you should not include results in the introduction. The introduction sets up the rationale and the aim, while results belong in the Results section. The main exception is when a journal format encourages an upfront “main finding” statement, or when you need a brief contextual fact to motivate the study, but even then you should not report your own outcome data as part of the justification. If you find yourself relying on your findings to “prove” the study mattered, your introduction is missing a pre-results rationale.

What should the last paragraph of the introduction include?

The last paragraph should lock the argument in place and remove ambiguity about what follows. Include:

The research aim stated as a direct response to the gap

The approach, described at a high level (design, data source, or analytic strategy, without procedural detail)

A brief contribution preview, stating what your study will clarify or test

An optional paper roadmap if it is standard in your field (one sentence is usually enough)

If the last paragraph cannot be read as the logical conclusion of your gap statement, revise the gap or rewrite the aim until the dependency is explicit.

Try Introduction Section Feedback in thesify

Sign up for thesify for free, upload your draft, and run Introduction Section Feedback. Use thesify’s section-level feedback to check gap–aim alignment, problem significance, and literature positioning before submission.

Related Posts

Scientific Paper Discussion Section: How to Stress-Test Your Draft: Writing a scientific paper discussion section requires a difficult cognitive shift. You must pivot from the role of a neutral reporter—stating p-values and themes—to that of an analyst constructing an argument. It is the only section where you are allowed to tell the reader what your data means, but that license comes with strict boundaries. Is your discussion just repeating results? Use thesify to stress-test your interpretation, limitations, and future research for validity.

Step-by-Step Literature Review Guide with Expert Tips: A well-structured literature review does more than summarize sources—it shapes your research direction, strengthens your credibility, and ensures methodological soundness. This post defines a strong literature review, its purpose, and the key ways your literature review enhances your work. You’ll learn the types of literature reviews and how to choose the right approach as well as a step-by-step plan to writing your literature review.

Results Section Feedback: Improving Data Presentation: Is your results section mixing fact with interpretation? The most common struggle with writing Results is separating observation from interpretation. When you have spent months analyzing data, your brain naturally jumps to the "why" and "how." Learn how thesify’s new feedback tool helps you separate findings from commentary and fix reporting errors.