Scientific Paper Discussion Section Feedback: How to Stress-Test Your Claims

The scientific paper discussion section is where you interpret your findings, explain their significance, and tie them back to your research question, while keeping a clean boundary between what you observed and what you are inferring. That boundary is exactly where drafts often go off track: an interpretation quietly becomes a conclusion, and a conclusion starts to read like a causal claim, even when the study design only supports association.

In this post, you will stress-test your Discussion by linking each claim to a concrete result, calibrating causal and certainty language (many journals advise “association” wording outside randomized trials), and drafting design-specific limitations and feasible future research suggestions.

If you want the same checks applied to your own draft, thesify’s section-level discussion section feedback reviews interpretation, limitations, and future research at the section level.

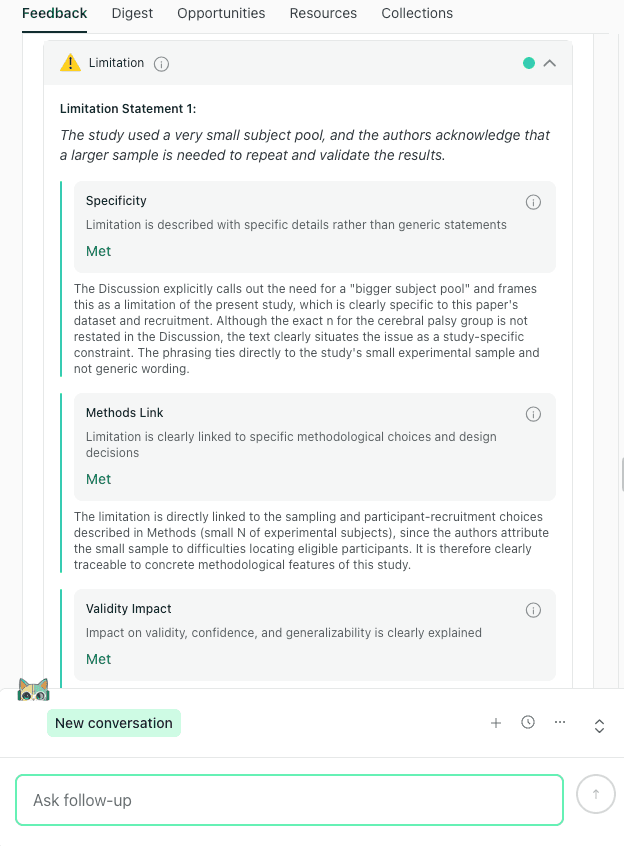

Discussion feedback is organised by interpretation, limitations, and future research, which makes it easier to revise the right part of the argument.

Results vs Discussion: Key Differences Reviewers Expect

The difference between the Results and the scientific paper discussion section is not stylistic, it is epistemic. Your results section reports what you found as transparently as possible, while your discussion section interprets what those findings mean, how they relate to your research question and prior work, and what limits should shape the reader’s confidence.

If you blur that boundary, you make it harder for a reviewer to evaluate the logic of your argument, because they cannot tell where the data end and your inference begins. That is why overinterpretation shows up repeatedly in studies of peer review as a reason manuscripts are rejected or heavily revised.

What Belongs in Results, What Belongs in the Discussion

This section helps you enforce a clean division of labour between reporting and interpretation.

In the Results section, you are primarily reporting. Typical “allowed moves” include:

Presenting outcomes in the order of your research questions or hypotheses.

Stating the direction, magnitude, and uncertainty of effects (or the structure of themes in qualitative work).

Pointing the reader to tables/figures and giving only the minimum framing needed to read them.

In the Discussion section, you are primarily doing interpretation. Typical “allowed moves” include:

Explaining what the results imply, and what they do not imply, given the design and analysis choices.

Connecting findings to prior literature and theory without rewriting your whole results narrative.

Making limitations explicit and translating them into bounded claims and concrete future research suggestions.

A quick, practical test you can apply line-by-line:

If the sentence answers “what did you observe?”, it belongs in Results.

If it answers “what does it mean, why might it be happening, or why does it matter?”, it belongs in the Discussion.

Example (same finding, different section):

Results-style: “Group A had lower mean symptom scores than Group B at follow-up (mean difference = X, 95% CI Y–Z).”

Discussion-style: “This pattern is consistent with [mechanism/interpretation], but the design limits causal inference, so the finding should be read as an association rather than evidence of an effect.”

If you want a dedicated workflow for tightening Results before you write the Discussion, you can cross-check your draft against the transparency-oriented checklist in Scientific Paper Results Section Feedback: How to Audit Your Draft for Transparency and Rigor.

The Most Common Boundary Violation: Interpretation Creep

Interpretation creep happens when Results sentences start doing Discussion work. It is a subtle form of overclaiming where a reported pattern turns into an argument.

Common creep signals in Results (highlight these):

“This suggests/indicates/implies…” (inference)

“Importantly/interestingly…” (evaluative stance)

“Because/due to/as a result of…” (causal explanation)

“This demonstrates/proves/confirms…” (certainty inflation)

How to fix creep without making Results sterile:

Strip inference verbs in Results, keep the observable.

Replace “This suggests that X” with “X was observed” or “X was associated with Y,” then move the “why it matters” sentence to the Discussion.

Move explanations into a Discussion “interpretation paragraph” that is explicitly bounded. A simple two-sentence pattern works well:

Sentence 1: your interpretation, stated as a proposal (“One interpretation is…”)

Sentence 2: your boundary condition (“However, because…, this cannot establish…”)

Watch for mismatch across sections. A common reviewer irritation is when the Results are careful, but the Discussion or abstract switches into stronger causal or action language. That inconsistency is documented in analyses of observational research reporting, and it is one reason “stress-testing” the claim language across sections pays off.

If you want a structured way to spot these boundary violations while drafting, thesify’s section-level feedback is designed to separate reporting issues from interpretation issues across IMRaD, so you can see where the argument starts to outpace the evidence.

Discussion feedback sits alongside other sections, which helps you keep Methods, Results, and interpretation consistent.

Stress-Test Your Discussion Section for Evidence-Linked Claims

In the scientific paper discussion section, reviewers are reading for one thing before anything else: whether your interpretive claims are proportionate to the evidence you have actually reported. Overinterpretation is a common reason reviewers push back on the Discussion. It often appears in small, local moves: a verb that implies causality, a generalization that outruns the sample, or a mechanism presented as if it were observed.

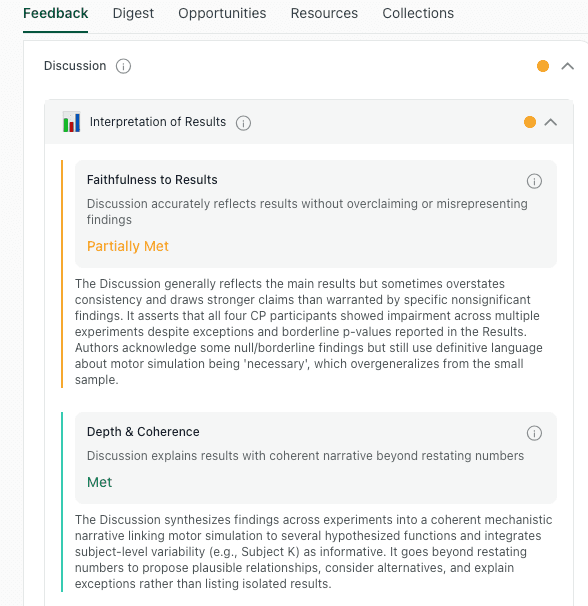

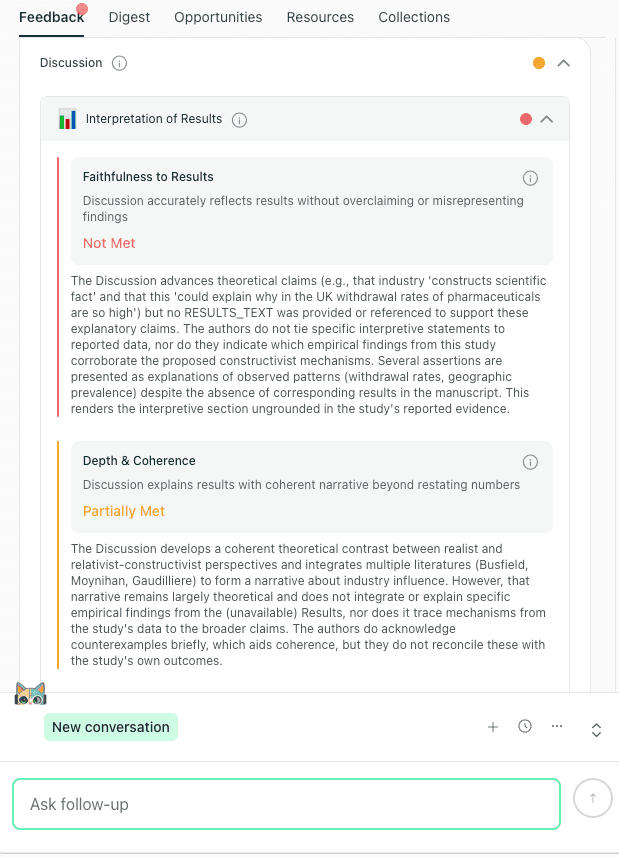

A useful way to draft (and revise) is to treat the Discussion as a chain of claims. Ensure every assertion is explicitly tied to a result, a study-design constraint, and an acceptable level of certainty. thesify’s feedback automates this "stress-test" by auditing your draft for Faithfulness to Results and Depth & Coherence.

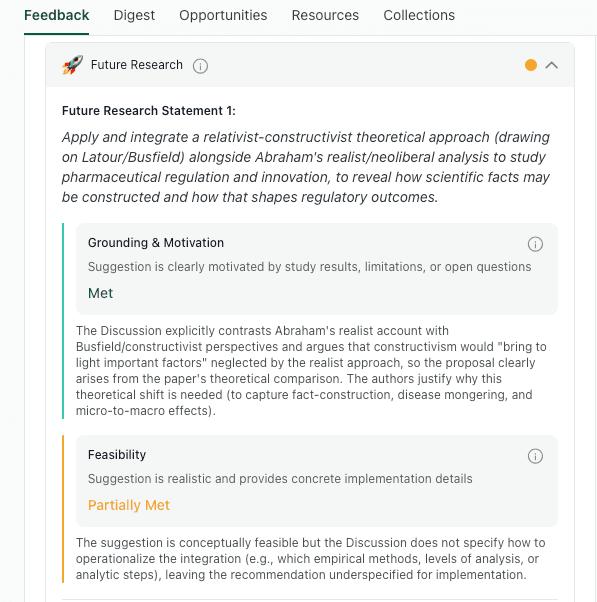

thesify breaks discussion interpretation into Faithfulness to Results and Depth and Coherence, so you can see whether claims stay anchored in evidence.

Build a Claim-to-Result Link for Every Paragraph

A Discussion section paragraph should be anchored by a single claim that a reader can trace back to something in your Results. If a claim cannot be traced, it is usually one of three problems: the claim is too strong, the Results are missing the needed supporting detail, or the claim belongs in the limitations or future research section.

Example of a Faithfulness to Results issue, where the Discussion advances explanations without pointing to specific results that support them.

This is the failure mode your claim-to-result link is designed to prevent: a reader cannot trace the interpretation back to a table, figure, statistic, or theme presented in the Results.

A simple claim-to-result link template (copy-paste into your draft notes):

Paragraph claim (1 sentence): What are you asserting, in plain academic language?

Result anchor: Which table/figure/quoted theme/estimate supports it?

Inference type: description, interpretation, explanation, or implication?

Design constraint: what about your methods limits this inference (confounding, measurement, selection, temporality, etc.)?

Calibration check: does the verb match the inference (associated with vs caused by)?

The 3-Minute Diagnostic:

Highlight the first sentence of every Discussion paragraph.

In the margin, write the specific table, figure, or statistic from your Results that supports it.

If you cannot write a number or label, that paragraph needs revision.

thesify simulates this diagnostic by flagging "weak analysis patterns" where new facts are introduced without analysis, or where claims are made without direct support from the text. This ensures your logic remains legible: reviewers can disagree with your interpretation, but they must respect the claim-evidence trail.

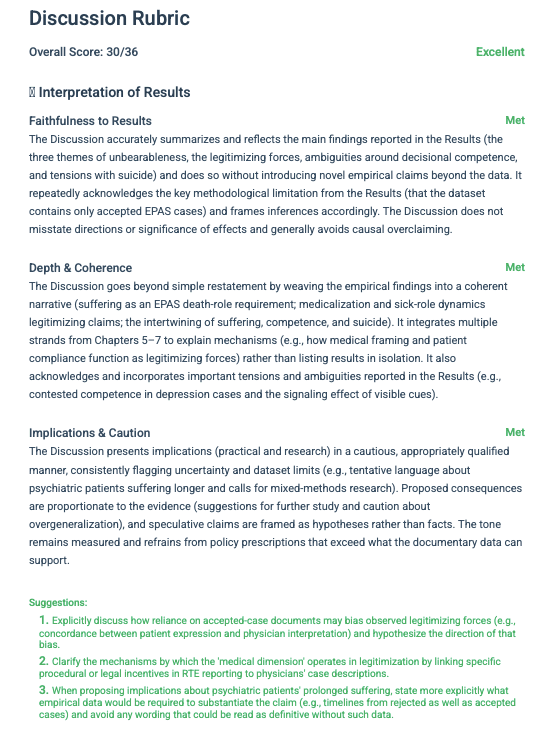

The downloadable report provides a high-level audit of your Interpretation, checking Faithfulness, Depth, and Implications.

Synthesize With Prior Literature Without Overreaching

Synthesis is where many “safe” Discussions fail. Authors restate their results, then paste in a generic citation block ("This aligns with Smith, 2020"). A stronger move is to use the literature to do comparative interpretation, not decoration.

A Disciplined Synthesis Pattern:

Position your finding: "In our sample, we observed X (direction/magnitude)."

Compare to literature: "This aligns with Y, but differs from Z, which reported..."

Explain cautiously: "One plausible explanation is [mechanism], although our design cannot adjudicate between [alternative explanation], so this should be interpreted as..."

thesify checks for Depth & Coherence to ensure you are integrating findings into the broader field rather than treating the Discussion as a restatement of the Results.

Depth and Coherence feedback highlights when the Discussion reads like a summary, and prompts you to build a clearer explanatory thread.

Use this feedback to catch instances where you might be using citations to "upgrade" your design (e.g., citing an RCT to imply your observational finding is causal).

Two guardrails that prevent overreach:

Do not use the literature to ‘upgrade’ your design. Citing an RCT does not turn an observational association into an effect.

Do not smuggle mechanisms in as findings. If you did not measure the mechanism, label it as a hypothesis, not a conclusion.

If you want a practical drafting habit: write your synthesis sentence in a way that makes it easy for a reviewer to disagree. That usually forces you to mark what is evidence and what is interpretation.

The Causal Slip: Avoiding Overclaiming

The causal slip is a common language problem in academic writing with methodological consequences. It happens when your Discussion uses causal verbs (“leads to”, “determines”, “drives”) even though the study design supports, at best, association. Analyses of published observational work show that this slippage is common, including in abstracts, where readers often encounter the claims first.

Stress-test your causal language by auditing verbs

Causal verbs (high burden of proof): causes, leads to, results in, determines, prevents

Associational verbs (lower burden, often appropriate): is associated with, correlates with, is linked to, co-occurs with

Interpretive phrasing (good for Discussion when bounded): is consistent with, may reflect, could indicate

If your design is observational, thesify will flag "unqualified causal language" as a validity risk. The fix is not to ban the word "cause" on principle, but to align the force of your verb with the strength of your identification strategy.

A practical rewrite rule

If your design is observational and you have not stated an explicit causal identification strategy (and its assumptions), default to associational language, then add one sentence that names the constraint (confounding, temporality, selection).

This is not about banning the word “cause” on principle. It is about aligning the force of your claim with what your data and assumptions can justify, and making those assumptions visible when you do aim for causal inference.

Integrate Null and Mixed Findings Instead of Hiding Them

Null and mixed findings are not an embarrassment, they are part of the evidentiary landscape. The problem is how they are interpreted. Non-significant results are frequently misread as evidence of “no effect,” when they may instead reflect limited precision, measurement constraints, or heterogeneity.

How to Write About Nulls Without Hand-Waving:

State what the data can support: “We did not observe clear evidence of a difference in X under Y conditions.”

Report precision, not just a p-value: if you have CIs or effect size estimates, use them to show what effect sizes remain plausible.

Offer bounded explanations: power, measurement sensitivity, timing, subgroup heterogeneity, or competing mechanisms (and say which is most plausible given your design).

thesify prompts you to address heterogeneous effects—such as when an intervention works for one group but not another—rather than burying them. For example, explicitly noting that a pattern was "not observed in [subgroup]" demonstrates methodological maturity and preempts reviewer critique regarding publication bias.

thesify prompts you to integrate null or contradictory findings into your theoretical narrative rather than ignoring them.

A useful sentence frame for mixed findings

“The association was present for A but not for B, which may indicate [heterogeneity/measurement/context], however, this pattern should be treated cautiously because…”

There is also a cultural reason to handle nulls cleanly: publication bias and selective attention to “positive” findings are widely discussed problems in the literature, so showing you can interpret nulls competently signals methodological maturity.

State Implications at the Right Level of Certainty

Implications are where reviewers look for inflation. You can often keep the Discussion persuasive by being more specific, rather than more certain.

Implications feedback prompts you to qualify general claims with scope limits and inferential constraints, so the takeaway matches what the study can support.

Calibrate Your Implications:

Level 1 (Results): What the study shows in your sample.

Level 2 (Interpretation): What the pattern implies, given limitations.

Level 3 (Application): What clinical or policy action follows.

If you make a Level 3 recommendation from Level 1 evidence, thesify will flag this as overclaiming. The tool checks if your "strong practice directives" are qualified by your generalizability limits (e.g., specific national contexts or populations) . Pair every broad implication with a boundary condition to ensure your advice is robust.

The audit checks if your implications are grounded in data or if you are making unsupported macro-level claims.

Two rules that prevent certainty inflation

Pair any broad implication with a boundary condition (population, setting, timeframe, measurement).

If you make an action recommendation from non-randomised evidence, explicitly justify why the leap is warranted, and what assumptions you are making.

Write Research Limitations That Are Design-Specific

The limitations section of your Discussion is where you define the boundary conditions of your inference. A reader cannot do much with a generic line like “the sample size was small” unless you specify what that constraint changes, whether it affects precision, generalisability, measurement validity, or the plausibility of alternative explanations.

If you want a high-level benchmark, reporting guidance for observational studies explicitly asks authors to discuss limitations in terms of likely sources of bias or imprecision, including the direction and magnitude of potential bias. That is the standard you are aiming for: limitations that are traceable to your Methods and interpretable as limits on what your results can support.

The tool prompts you to replace generic "boilerplate" limitations with constraints tied specifically to your methodology.

A practical drafting rule is to make each limitation “point back” to a concrete Methods choice. If you cannot point to the design, sampling frame, measures, time window, or analytic decision that generated the limitation, you are usually writing commentary rather than methodological constraint. This is also why it helps to keep your Methods and Results tight before you draft limitations (see our companion posts on Methods and Results feedback).

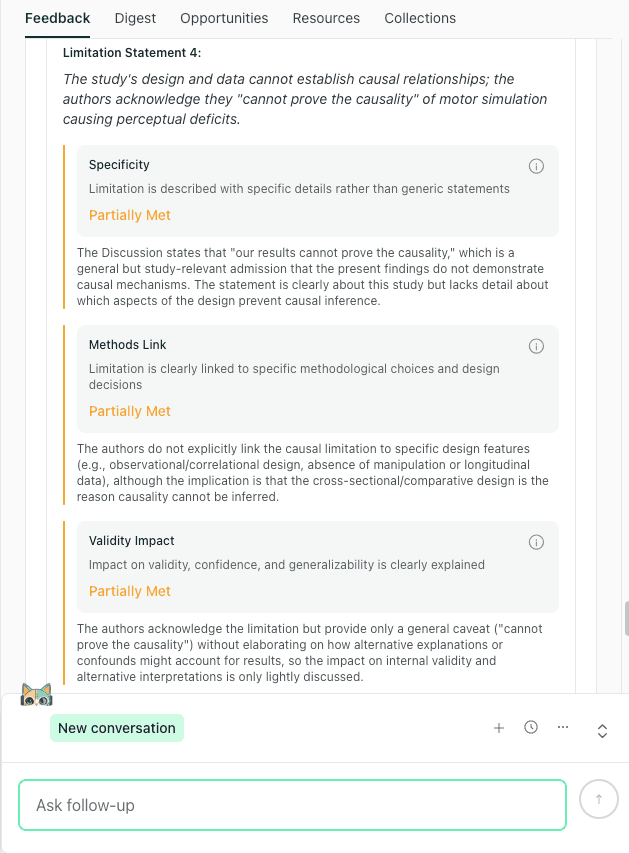

Example of a limitation that acknowledges causality limits, but needs design-specific detail to explain what prevents causal inference and how that affects validity.

The Boilerplate Limitation Problem

If your limitation sentence could be dropped into any paper in your field without changing a word, it is boilerplate. Boilerplate is not “wrong,” it is just uninformative, because it does not tell the reader what your study can and cannot conclude.

A fast boilerplate test

Can you finish the sentence: “This matters because…” in a way that is specific to your design and measures?

Can you name which inference it restricts (causal interpretation, external validity, measurement validity, precision)?

Could a reviewer reasonably ask, “So what changed in your conclusions because of this?”

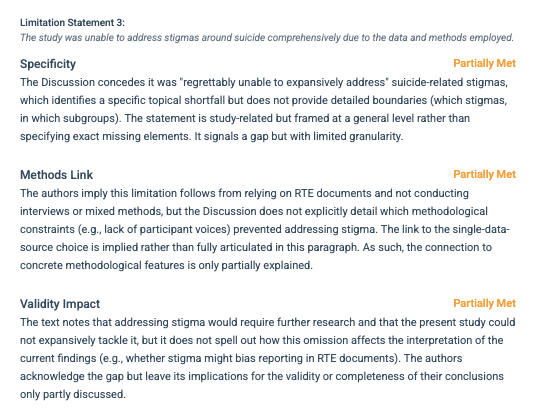

If a limitation is too generic (like "stigma"), thesify’s feedback prompts you to specify the boundary it creates for your specific data source .

Example: turn a generic limitation into a design-specific boundary

Boilerplate: “Language bias is a limitation.”

Design-specific: “Because the search strategy used English-language terms and databases, locally delivered programmes in non-English settings may be underrepresented, which limits the generalisability of implementation conclusions to English-indexed contexts.”

Notice what the rewritten version does: it names the methodological choice (search strategy), the likely distortion (underrepresentation), and the inference it restricts (generalising implementation claims).

A 3-Part Limitations Template Reviewers Trust

Most reviewers are not asking you to list every possible weakness. They want to see whether you understand how your methods shape what your results can support. A clean way to show that is to structure each limitation with three parts:

Constraint: what is missing, restricted, or imperfect?

Mechanism: how does this follow from your method or data source?

Consequence: what does it change about interpretation, including (when relevant) likely direction of bias?

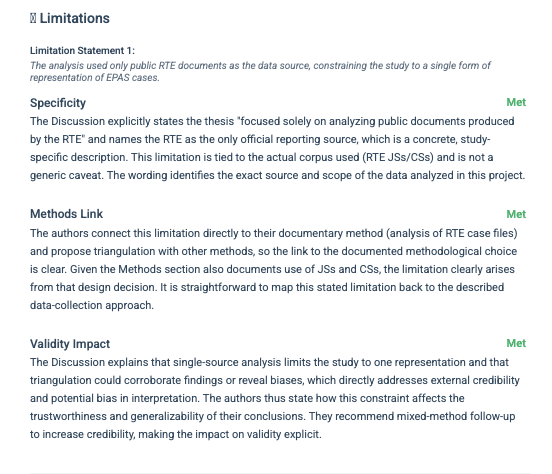

thesify checks your limitations against three specific criteria: Specificity, Methods Link, and Validity Impact

This aligns well with how major reporting guidance frames limitations, especially the expectation that you discuss bias and imprecision in a way that makes their impact interpretable.

Copy-ready template (use one limitation per paragraph or per sentence cluster):

Constraint: “A limitation of this study is [specific constraint].”

Mechanism: “This arises because [methodological reason tied to Methods].”

Consequence: “As a result, [the specific inference that is restricted], and the association/effect may be [overestimated/underestimated/uncertain], depending on [brief rationale].”

A strong limitation ties the constraint to a methods choice and explains the validity impact, so the reader can see exactly what the finding can and cannot support.

Worked example (conceptual, adapt to your study):

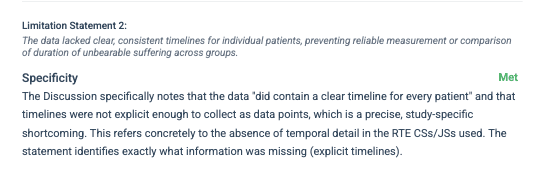

Constraint: “Individual timelines could not be consistently extracted.”

Mechanism: “Public documents did not report start dates and duration in a standardised format across cases.”

Consequence: “This limits comparisons of duration across groups and increases uncertainty around any claim about escalation or trajectory.”

A "Met" score on Specificity requires identifying exactly what information was missing (e.g., explicit timelines) rather than just stating data was imperfect.

A small but high-impact detail is to name whether the limitation primarily affects:

Internal validity (bias, confounding, misclassification),

Precision (wide uncertainty, low power),

External validity (transportability to other settings),

Construct validity (whether your measures capture the concept you claim).

Design-Linked Limitation Starters

Below are sentence starters that keep your limitations anchored to study design. The goal is not to sound cautious, it is to be specific about what the design can support.

Cross-Sectional Designs

“Because exposure and outcome were measured at the same time point, temporal ordering cannot be established, which restricts causal interpretation of the association between X and Y.”

“Unmeasured confounding remains plausible in this design, so observed associations should be interpreted as correlational rather than evidence of an effect.”

Single-Source Data (for example, one document set or one registry)

“Relying on a single source of records restricts the analysis to what that source captures and how it frames cases, which may omit contextual factors not recorded in the source.”

“Because the data were not created to answer the present research question, misclassification and missingness may not be random, which can bias estimates and should be considered when interpreting direction and magnitude.”

Online Surveys

“Self-selection into an online survey may produce a sample that differs systematically from the target population, which limits generalisability.”

“Social desirability and recall error may bias self-reported measures, which can attenuate or inflate associations depending on the direction of misreporting.”

If you are writing this section alongside your Discussion interpretation, it helps to cross-check for consistency: the more cautiously you describe what the design supports in limitations, the more your claim language elsewhere needs to match that constraint. In thesify’s section-level feedback workflow, this is exactly the handoff between Methods, Results, and Discussion that the rubric is trying to make visible.

Turn Future Research Suggestions Into Feasible Next Studies

“More research is needed” is rarely wrong, but it is rarely helpful. In a strong scientific paper discussion section, future research suggestions do a specific job: they translate the limits of your current evidence into a concrete next study that another researcher could plausibly run.

Reporting guidance for observational research explicitly asks authors to discuss limitations and interpretive constraints, and the logical follow-on is that your “what next” should address those constraints in a way that is operational rather than aspirational.

This is also where vague writing triggers reviewer skepticism. If your future directions read like a list of interesting topics, they can appear disconnected from your findings—an attempt to gesture at importance without doing the design work.

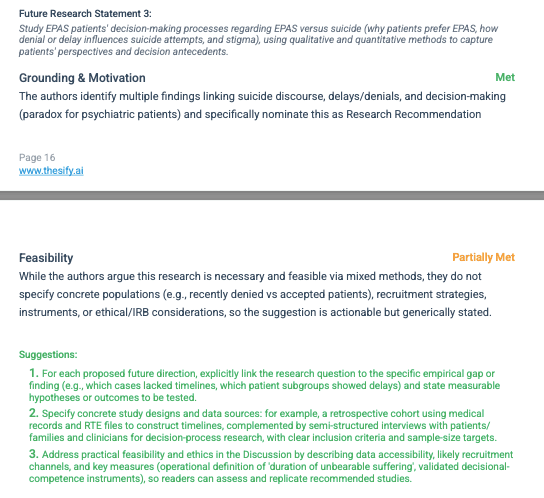

The feedback flags suggestions that lack concrete populations or metrics as "Partially Met," prompting you to add operational details.

A better standard is simple: a future research suggestion should specify the minimum design details needed to test the claim you could not test here.

thesify reviews this part of your Discussion for feasibility, checking whether each proposed direction is concrete enough to be implementable, and whether it follows from your results and limitations rather than from general curiosity.

thesify reviews whether your suggestions are logically motivated by your study's specific findings and limitations

The Vague Wishlist

A common failure mode in future research suggestions is what you can think of as the “wishlist”: the direction is academically sensible, but not specified enough to evaluate.

Typical wishlist lines include:

“Longitudinal research is needed…”

“Future studies should explore mechanisms…”

“Cross-country replication would be valuable…”

The problem is not the idea. The problem is that it leaves the reader unable to answer basic questions: Which design? Which population? What data? What would count as confirming or disconfirming the interpretation?

A fast wishlist test

If you removed the topic words (for example, “longitudinal” or “replication”), would the sentence still tell a researcher what to do next? If not, you need at least one operational detail.

thesify’s feedback flags suggestions that lack concrete study designs, populations, or metrics as "Partially Met."

Turn this into an actionable protocol (quick fixes)

Instead of “longitudinal,” state the unit and time window: “a 6-month cohort with monthly follow-up,” or “a 14-day diary study.”

Instead of “replication,” state the boundary you want to test: “replication in [setting] where [key condition] differs.”

Instead of “mechanisms,” state the measurable mediator or competing explanation and how it would be tested.

This is the same principle you use throughout your scientific paper discussion section: claims are easier to trust when the evidence path is explicit.

thesify checks whether future research suggestions are grounded in results and limitations, and whether feasibility details are concrete enough to implement.

Feasibility Checklist for Future Directions

To make your future research suggestions reviewer-proof, build each one around three operational details. You do not need a full grant proposal, you need enough information for the reader to see that the design matches the gap.

1) Design: What study would actually answer the question? Write the specific method, not a genre label.

Instead of “further study”:

“a retrospective cohort using medical records”

“a mixed-methods study combining interviews with routine data”

“a cluster trial”

“a qualitative comparative case study.”

2) Population/Setting: Who and where, and why that boundary matters? Name the recruitment frame or context that connects to your limitation.

“Patients at point of diagnosis,” “women presenting to primary care clinics,” “cases documented in [registry/source] between [years].”

3) Measurement: What variables or outcomes will adjudicate the interpretation? Identify the key constructs and how they will be operationalised.

“Validated trust scale at baseline and follow-up,” “structured coding of symptom trajectories,” “exposure timing and outcome onset dates,” “policy implementation markers.”

If you want an extra layer of precision (often worth a single clause), include one of:

the comparator condition

the primary endpoint

the minimum follow-up needed to observe change

Future Research Sentence Templates

Future directions read strongest when they solve a specific inferential problem you have already named in limitations or interpretation. That keeps the logic tight and reduces the sense of “tacked-on” ideas.

Template:

“To address [Limitation], a [Design] study in [Population/Setting] could measure [Key Variables] to test whether [Bounded Hypothesis].”

Example (adapt the details to your paper):

“To address the lack of temporal ordering in our cross-sectional data, a 6-month prospective cohort study in newly diagnosed patients could measure information-seeking behaviour and trust at monthly intervals to test whether increases in information seeking precede changes in trust.”

Variant for mixed or null findings:

“To clarify why the association appeared in [Subgroup A] but not [Subgroup B], a [Design] study could oversample [Subgroup] and measure [moderator/measurement difference] to test whether [heterogeneity explanation].”

Why this works is straightforward: it links the proposed study to a specific weakness in the current evidence, which makes the suggestion grounded rather than speculative, and easier for a reviewer to read as scientific planning rather than rhetorical flourish.

If you want to align this section with the product promise, thesify’s Discussion feedback is designed to flag future research suggestions that are too general, and to prompt for the missing operational details that make feasibility legible

Discussion Section Checklist: A Reviewer-Style Stress-Test

Before you submit, run your draft through this checklist. These are the specific dimensions thesify evaluates to determine if your manuscript is ready for peer review.

1. Interpretation & Faithfulness

Anchored Claims: Does every interpretive claim in the Discussion reference a specific table, figure, or statistic from the Results?

Causal Calibration: If your study is observational/cross-sectional, have you removed all definitive causal verbs (e.g., determines, impacts) and replaced them with associative ones (e.g., is linked to, suggests)?

Null Handling: Have you explicitly discussed hypotheses that were not supported, rather than ignoring them?

2. Limitations & Rigor

Specificity: Do your limitations name the specific mechanism of bias (e.g., "English-only search terms") rather than generic categories (e.g., "Language bias")?

Validity Impact: Does each limitation statement explain how the constraint restricts your conclusions? e.g., "This prevents generalizing findings to non-digital native populations".

Methodological Link: Is every limitation traceable to a specific choice described in your Methods section?

3. Future Research & Impact

Feasibility: Do your future research suggestions include a proposed design, population, or variable? (Avoid "Further research is needed" without elaboration).

Implication Scaling: Are your recommendations for practice or policy proportionate to your sample size and effect strength?

Scientific Paper Discussion Section FAQs

What is the difference between Results and Discussion in a scientific paper?

The results section reports what you found, and the scientific paper discussion section interprets what those findings mean and why they matter. In practice, Results stays descriptive (numbers, patterns, themes), while Discussion explains significance, context, and limits, without re-running the analysis on the page.

Can I Introduce New Results in the Discussion?

Generally, no. The Discussion should interpret findings you have already presented in the Results, rather than introducing new statistics, outcomes, or themes for the first time. A useful rule is: if the reader needs a new number to believe your point, that number belongs in Results (or in a table/figure you have already introduced).

How Do I Write Limitations Without Undermining Credibility?

Write limitations as design-specific constraints on inference, not as generic admissions. Good limitations name:

The methodological source of the constraint (sampling, measurement, confounding, missingness)

What it changes about interpretation, ideally including the likely direction of bias or uncertainty when you can. That is close to what reporting guidance such as STROBE asks authors to do in the Discussion.

What Verb Tense Should I Use in the Discussion Section?

Use past tense for what you did and what you found in your study (methods and results), and present tense for general statements, established knowledge, and parts of the interpretation that you present as current understanding. Many discussions mix both in the same paragraph: past tense to summarise your finding, present tense to interpret its significance.

Try Discussion Section Feedback in thesify

Sign up for thesify for free, upload your draft, and open Discussion Section Feedback to review your Interpretation, Limitations, and Future Research against common reviewer expectations for the Discussion section.

Related Posts

Scientific Paper Results Section: How to Get Feedback: Is your results section mixing fact with interpretation? Getting an objective look at your own data presentation is difficult. You know what your findings mean, so it is easy to accidentally skip over the detailed, neutral reporting that the reader requires. Learn how thesify’s new feedback tool helps you separate findings from commentary and fix reporting errors.

Get Better Methods Section Feedback: A Step‑by‑Step Guide: Looking for practical guidance on drafting or improving the methods section of a scientific paper, ensuring reproducibility, and understanding peer review expectations? This article offers actionable checklists and instructions on how to use tools like thesify for structured feedback. Discover how thesify’s section‑level feedback helps you refine your methods section. Clarify design, sampling, data collection and analysis for reproducible research.

PhD by Publication Discussion Chapter: Synthesis Template: Writing the PhD by publication discussion chapter is different from writing a standard thesis discussion because you are integrating findings from multiple published papers into one coherent argument. Learn how to write the discussion chapter for a PhD by publication, with structure, cross-paper synthesis, examiner expectations, and a pitfalls checklist.