Mapping the Conversation: How to Identify and Synthesize Key Research

You can present robust data and rigorous analysis, yet still face rejection because your writing does not clearly position your study within the existing academic discourse. This isolation often manifests in reviewer feedback asking, “How does this relate to [Key Academic]?” or “The discussion lists studies rather than engaging with them.” These comments signal a failure to map the disciplinary territory. In most cases, the issue is not coverage, it is synthesizing literature so the field’s argument structure becomes visible.

To position your research effectively, you must be able to answer one question with precision:

“Which existing studies or theorists contributed significantly to this discussion, and what are their main arguments?”

thesify identifies gaps in your draft where you have failed to explicitly name the researchers and arguments shaping your topic.

Answering this requires treating academic discourse not as a chronological timeline of publications, but as an evolving argument. Your task becomes identifying the specific lineage of ideas that makes your research question necessary.

This guide provides a structured methodology for identifying seminal works, extracting their core arguments—beyond merely reporting findings—and synthesizing literature to reveal exactly where your project fits. By the end, you will move from summarizing authors to constructing a critical narrative that validates your specific contribution.

Synthesizing Literature vs Summary: The Role of Critical Synthesis

What is a Synthesis of Literature?

A synthesis of literature organizes existing research by theme, argument, or debate rather than by author. It shows how key studies and scholars agree, diverge, or build on one another, so you can justify your research question and explain your entry point. This is the core skill behind synthesizing literature.

Distinguishing Summary from Critical Analysis

Reviewers frequently distinguish between a summary, which lists findings, and a synthesis, which evaluates the relationships between them. A summary typically follows a "siloed" structure: Author A found X. Author B found Y. While this proves you have read the material, it fails to advance an argument.

Critical analysis requires restructuring these findings to reveal the state of the field. Instead of listing authors, you group them by the position they hold. For example: While Author A focuses on X, Author B argues Y, creating a tension regarding Z. This shift allows you to move beyond reporting data to interpreting the academic discourse surrounding your topic.

Moving from summary to synthesis requires explaining how specific evidence supports your broader disciplinary claims.

Summary vs. Synthesis: A Functional Comparison

A summary reports what each study did; a synthesis explains how those findings interact to create a "map" of the field’s current knowledge.

Use the following functional comparison to audit whether your writing is performing a synthesis of literature or a descriptive summary.

Feature | Summary | Synthesis |

What You Write | Reports what each individual study found. | Explains how different claims relate to one another. |

Organization | Organized by author or publication date. | Organized by theme, debate, or conceptual tension. |

Core Claim | "This is what has been done." | "This is what we know (and what remains disputed)." |

Common Failure | Author-by-author "laundry lists." | Over-generalization without specific evidence. |

Establishing Disciplinary Lineage

Your reader should be able to see the disciplinary lineage of your research question. This means tracing the specific chain of arguments that makes your study valid.

By identifying the seminal works and subsequent debates, you show that your research question is not an arbitrary invention but a logical next step in an established conversation. If this lineage is unclear, the significance of your eventual research gap will be difficult to justify. A strong synthesis answers the question: On whose authority does this study rest?

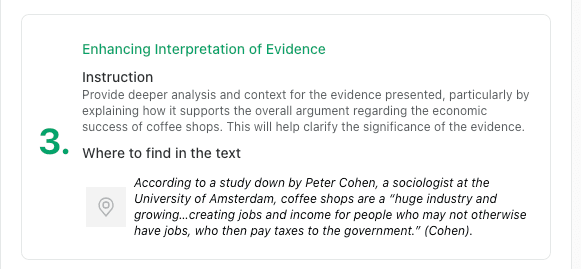

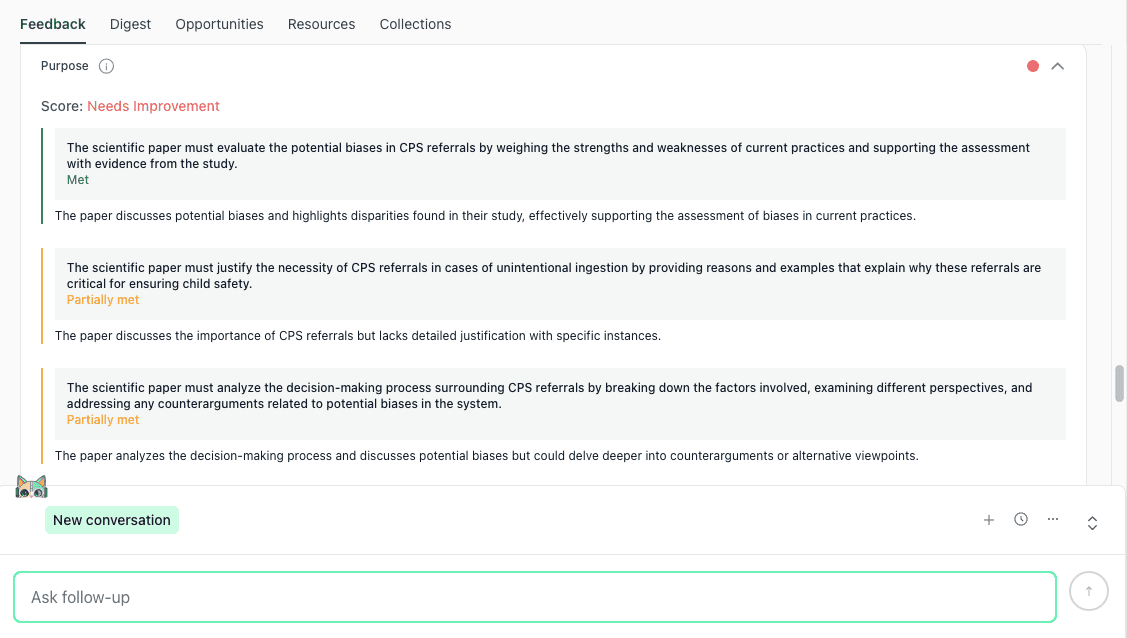

Example of thesify feedback prompting historical grounding and source-backed claims.

Identification: Locating Seminal Works and Key Contributors

To construct a synthesis that satisfies peer review, you must first identify which researchers have shaped the current state of the field. Establishing this disciplinary lineage is a prerequisite for a credible introduction structure. If you fail to account for the foundational research your study inherits, your subsequent arguments will lack the necessary academic authority.

One practical check is whether your draft makes the “must-address” concepts and contributors visible early, especially where you define key terms and summarize what the field agrees and disagrees on. This is also the kind of gap that often appears in thesify’s Purpose feedback when definitions or the structure of key points are still too implicit.

Example of thesify Purpose feedback highlighting clarity and structure issues in literature-driven sections.

Your goal is to identify the sources that shaped the conversation you are entering, meaning the ideas, definitions, and argumentative moves that later research inherits, revises, or contests.

What “Key” Actually Means in Academic Discourse

In academic discourse, a source is “key” when other scholars treat it as a reference point rather than a single data point.

A practical classification helps you choose contributors you can justify in writing:

Foundational: Introduces a definition, framework, or method that later work adopts or must respond to. In your literature discussion, this is often where you anchor what your central concept means and what counts as a valid approach.

Turning point: Shifts the dominant explanation, exposes a limitation in prior work, or reframes the problem. These are the sources that usually create “before and after” logic in a field.

Consolidator: A systematic review, meta-analysis, or authoritative synthesis that stabilizes what is known and identifies the main disputes. These are useful for locating recurring citations and recurring problem statements efficiently.

Current frontier: Recent work that advances, re-argues, or pressure-tests an existing position. These sources show where the discourse is moving now and where the open questions are.

This classification keeps your “key” list defensible. You can name a source’s role in the discourse rather than relying on a vague claim that it is “important.”

Defining Significant Contributors: Foundations vs. Current State

Effective identification requires distinguishing between the authors of recent empirical studies and those who produced seminal works. While both are necessary, they serve different functions in your writing:

Seminal Works (Foundational Paradigms): These are the works that established the core concepts, theories, or methodologies within a discipline. They are often older, highly cited, and provide the "language" of the field.

Current State Research: These are peer-reviewed articles published within the last three to five years. They represent how the field is currently testing, refining, or contesting those foundational paradigms.

By distinguishing these two categories, you demonstrate that you understand both the origin of the academic conversation and its most recent developments.

Methodology 1: Backward Chaining from Meta-Analyses

Identifying foundational research is most efficiently achieved through "backward chaining." A reliable way to locate foundational research is to start from a small number of high-quality overview texts, then work backward.

Start with one or two strong reviews, handbooks, or field-defining syntheses that closely match your topic.

As you read, extract two things: recurring citations (the same names or studies appearing repeatedly) and recurring problem statements (the same unresolved tension, limitation, or conceptual disagreement).

Use those recurrences to build a shortlist of must-address works. Your goal is a short set of sources that explain why the debate looks the way it does.

This method allows you to move from the "branches" of current discourse directly to the "roots" of the field. Neglecting this step often leads to early reviewer comments about a lack of historical or conceptual grounding, one of the first structural gaps reviewers tend to notice.

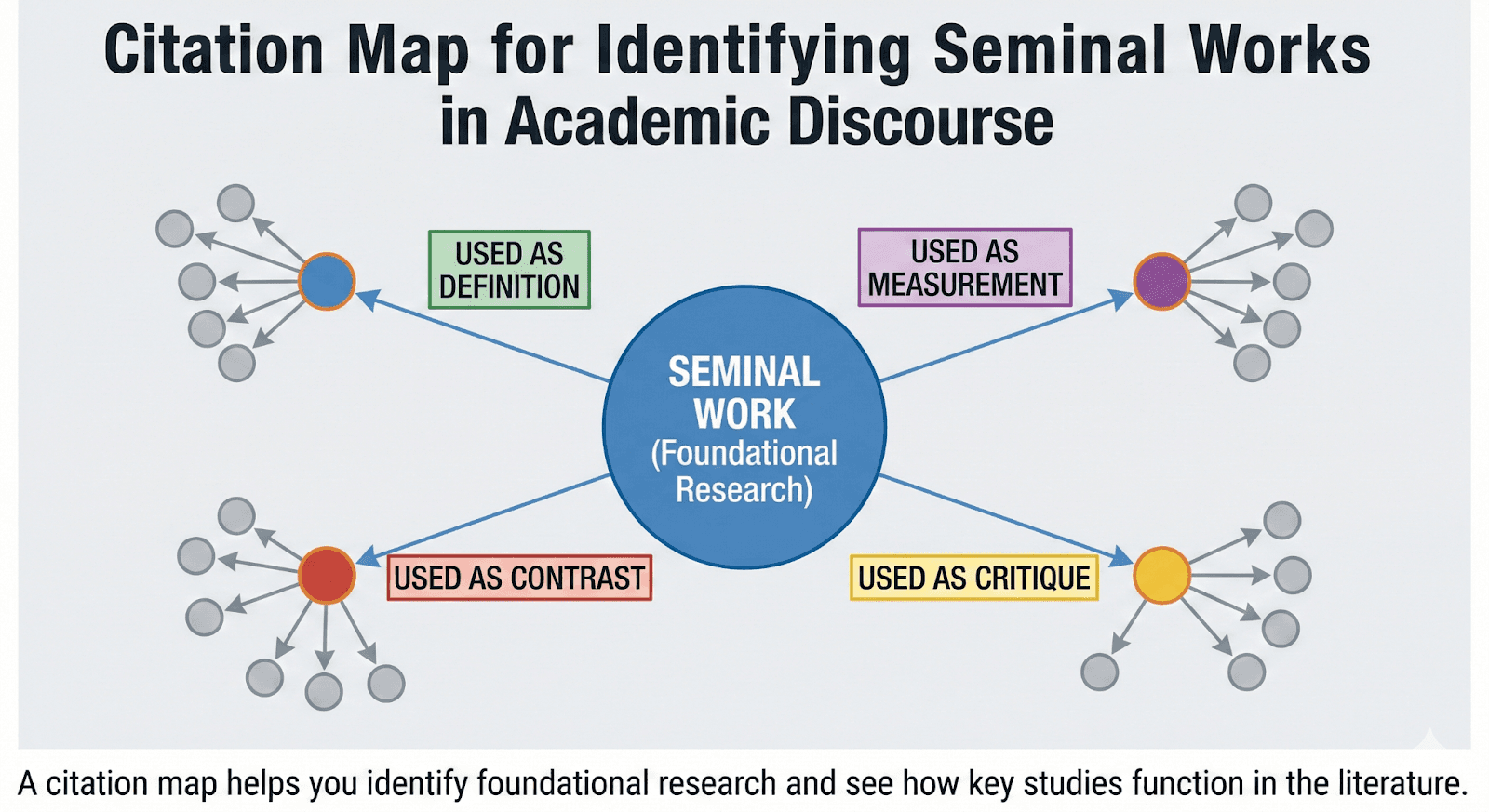

Methodology 2: Evaluating Citation Context

Once you have a shortlist, do a fast “citation context” check to understand why each work matters. Do not treat citation counts as the argument. Treat them as a pointer to influence.

Look at how other papers cite the work and label the citation function:

Used as definition (the source fixes terminology or conceptual boundaries)

Used as measurement (the source sets an operationalization, instrument, or coding scheme)

Used as contrast (the source represents a competing position)

Used as limitation or critique (the source is invoked as a problem, warning, or boundary)

These labels make it easier to write synthesis later, because you can place each source into the conversation by role, not by chronology.

Evaluate whether the academic community is citing the work to apply its findings, refine its definitions, or refute its core premise. Understanding this context is necessary for your later Discussion Section, where you must justify why you are building on, or departing from, these established arguments.

Extract the Main Argument From Each Key Source

To move beyond descriptive summary, you must identify the main argument of a study rather than merely reporting its findings. While findings are the raw inputs of a paper, the argument represents the author's interpretation of those findings within a specific scholarly debate.

A functioning synthesis requires that you treat each source as a position in a conversation. This means determining not just what happened in the study, but what the author claims the results signify for the field.

The Argument Extraction Template (Reusable Mini-Worksheet)

Use the following template for every work you have identified as a significant contributor. Precision in this step prevents "author-by-author" reporting by forcing you to isolate the core logic of the text. If a field cannot be completed in one or two sentences, the source requires further critical reading before it is usable in your synthesis.

A common failure point is treating a definition or distinction as “covered” after repeating it once, without explaining what it rules in, rules out, or changes for your argument.

Example from thesify’s downloadable feedback report prompting deeper analysis of what a definition distinguishes, not only what it states.

Copy and paste this template into your research notes:

Claim: What is the central, debatable claim in one sentence? (Avoid topic labels; focus on the relationship between variables or concepts.)

Target: What prior view or established consensus is this work refining, replacing, or defending?

Reasoning: What is the logical bridge that connects the evidence to the claim?

Scope: In what contexts does the claim apply, and where are its boundaries?

Stakes: Why does this claim matter for the future direction of the field?

By completing this worksheet for 6–10 key sources, you establish a comparative foundation. Your writing task then shifts from description to critical analysis of literature, as you can now identify exactly where claims align or diverge based on their underlying logic.

Findings-to-Argument Rewrite Pattern

A reliable method for ensuring your writing remains at the level of analyzing research arguments is to translate results-based reporting into claim-based mapping. Use the following linguistic pattern to restructure your notes:

“The study reports X” → “The study argues X means Y, because Z.”

This structure forces you to articulate the author's interpretation and the reasoning behind it, which is the necessary "meat" of a high-level synthesis.

Example 1: Empirical Study

Reports: “Participants exposed to stimulus A showed a 20% increase in behavior B.”

Argues: “Exposure to A increases B, which supports the mechanism that external stimuli shape outcomes through cognitive pathway C.”

Example 2: Qualitative or Interview-Based Study

Reports: “Interviewees consistently describe the experience as unpredictable and stressful.”

Argues: “The phenomenon should be understood as a structural constraint rather than an individual preference, as participants link their stress directly to institutional conditions Y.”

Example 3: Historical or Conceptual Analysis

Reports: “Across the designated period, the institutional language shifts from terminology X to terminology Y.”

Argues: “The transition from X to Y reflects a fundamental redefinition of the problem, as the new framing alters who is positioned as responsible for the solution.”

Once you have reframed your sources using this pattern, you can begin to structure your literature review around these competing interpretations rather than the raw data points.

Build a Synthesis Matrix Before You Draft

Constructing a synthesis matrix is one of the most effective ways to stabilize your literature review structure. When you have a comprehensive reading list but find your draft reverting to a sequence of summaries, a matrix forces the comparative work required for true synthesis. It allows you to locate tensions and decide exactly what role each source plays in the broader academic discourse before you begin drafting.

The goal of a matrix is to move from "reading for content" to "mapping for argument." By organizing your notes into a grid, drafting becomes a task of assembly and critical analysis rather than improvisation.

The Synthesis Matrix Structure

To build your matrix, set up a grid where one axis represents your key sources and the other axis represents the core concepts, themes, or debates you have identified in the field.

For debate-driven fields: Use specific points of contention as columns (e.g., definitions of a key term, proposed mechanisms, evidence standards).

For concept-driven fields: Use your study’s core variables or concepts as columns, treating disagreements as patterns that emerge across the rows.

The effectiveness of the matrix depends on your cell entries. Avoid using topic labels such as “discusses gender” or “mentions social media.” Instead, use a controlled vocabulary of "argument moves" to record what the source does in relation to the debate:

Defines: Sets the conceptual boundaries or meaning of a key term.

Disputes: Directly challenges a claim, assumption, or previous finding.

Extends: Adds a new variable, population, or mechanism to an existing theory.

Limits: Specifies the conditions or contexts where a claim no longer holds.

Operationalizes: Transforms an abstract concept into a specific measure or procedure.

Reinterprets: Re-evaluates existing data through a different logical lens.

If your research requires a more rigorous comparative approach, you may find it helpful to adapt the logic from our comparative analysis research guide to organize your matrix by specific variables.

Turn the Matrix Into Debate-First Paragraph Plans

A matrix is most valuable when it serves as the blueprint for your paragraphs. When synthesizing literature, paragraphs should be organized around a tension or theme, not around an individual author’s publication history.

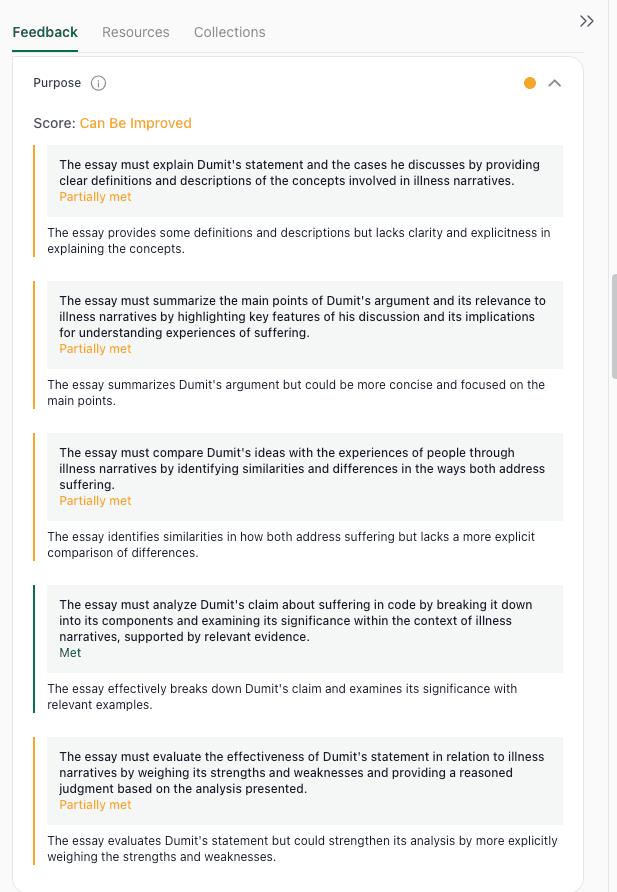

One way to test whether you are truly writing “debate-first” is to check whether your paragraph plan forces you to address competing explanations, counterarguments, or alternative viewpoints rather than presenting one line of reasoning in isolation.

Example of thesify feedback prompting deeper justification and explicit engagement with alternative viewpoints.

Use the following formula to convert a single column of your matrix into a paragraph:

Topic Sentence (The Debate): Identify the specific tension and state what is at stake for the field.

Evidence Sentences (Source Placement): Use your "argument move" labels to place 2–4 key sources into that debate.

Closing Sentence (The Residual Gap): State what remains unresolved or why this specific debate necessitates your current study.

Example Structure:

Topic Sentence: “Current accounts disagree on whether X should be treated as a stable attribute or a context-dependent process, which fundamentally alters how researchers interpret Y.”

Evidence Sentences: “While Author A defines X as [Definition], Author B disputes this by [Reason]. Author C extends the debate by demonstrating [Finding], yet Author D limits these conclusions to cases where [Condition].”

Closing Sentence: “This lack of consensus regarding the stability of X highlights a significant gap in the literature that the present study aims to address.”

thesify verifies that your body paragraphs use specific concepts and research to reinforce your central argument.

Sentence Templates That Signal Synthesis (Not Summary)

To maintain an analytical tone, use templates that explicitly encode comparison and lineage. These phrases signal to the reader that you are engaged in critical analysis of literature rather than mere reporting.

“Author A frames X as…, whereas Author B treats X as….”

“Across studies, X is consistent, but explanations for the phenomenon diverge on….”

“This disagreement turns on the underlying assumption that….”

“One prominent strand of research argues…, while another emphasizes….”

“Author A extends earlier claims by…, but Author B limits this application to cases where….”

“Although both accounts agree that…, they differ significantly in how they define….”

“Evidence is interpreted differently depending on whether X is conceptualized as….”

“A common approach operationalizes X as…, which Author B disputes on the grounds that….”

“Later work reinterprets these findings by shifting the analytical focus from… to….”

“Taken together, these studies suggest…, but they leave open the critical question of….”

“The current debate can be summarized as a trade-off between… and….”

“While the literature converges on…, it remains divided over the mechanism of….”

By organizing your thoughts through a matrix and using these templates, you ensure your literature review functions as a coherent map of the field rather than a fragmented bibliography.

Position Your Contribution Inside the Existing Discourse

Establishing the current academic discourse and identifying core arguments allows you to define your study's position within that landscape with precision. This phase of synthesizing literature is critical because it transforms a general review into a defensible research contribution. By articulating exactly what the field currently claims and where consensus fails, the significance of the study becomes clear to reviewers and supervisors.

Positioning should be approached as a strategic methodological move that specifies how your research alters what the discipline can claim, test, or interpret.

Three Legitimate Positioning Moves for Academic Research

Most authoritative positioning follows one of three methodological paths. The selection of a move depends on the specific tension identified in your synthesis matrix.

Refinement: This move involves adopting an existing definition, model, or mechanism but refining its scope, measurement, or application. It is appropriate when the discourse is stable on foundational concepts but lacks clarity regarding their generalizability or operationalization.

Application: “This study adopts [Author’s] definition of [concept] but refines the model by applying it to [new population], addressing prior limitations in [measurement].”

Adjudication: This move involves testing between competing accounts. It is necessary when the discourse contains two or more active explanations that make different predictions or interpret the same evidence using incompatible logic.

Application: “Where prior research diverges between Account A and Account B, this study adjudicates between them by examining evidence that both accounts claim to be decisive.”

Reframing: This move demonstrates that the current debate is organized around a questionable assumption or boundary. It is effective when disagreements persist because scholars are using incompatible definitions or treating a contested premise as settled.

Application: “This study reframes the debate by challenging the assumption that [premise], demonstrating instead that [alternative], which alters how the existing findings should be interpreted.”

These moves keep your contribution grounded in the discourse you just mapped, rather than in generic claims about novelty.

At this stage, a good check is whether your draft does more than explain one author’s view. Your literature discussion should also summarize the main argumentative line, compare positions, and evaluate strengths and weaknesses where relevant. This is exactly the kind of requirement that shows up in thesify’s Purpose feedback when a draft is still too descriptive.

Example of thesify Purpose feedback prompting clearer summary of main arguments, explicit comparison, and evaluation.

From here, you can link your positioning directly to your research gap language.

Integrating Positioning with Research Gap Language

Positioning is most effective when connected directly to the language of your research gap. A robust gap statement does not merely claim that a topic is "under-studied"; it argues that, given the specific discourse you have mapped, the field cannot yet answer a particular question under certain conditions.

To ensure your positioning leads directly to your research aims, utilize a structured linguistic sequence:

Convergence: State what is clearly established in the literature.

Divergence: Identify the live tension or disagreement between key contributors.

The Unresolved Point: Explain why this divergence leaves a specific question or mechanism unanswered.

The Contribution: State how your study addresses that gap through a specific refinement, adjudication, or reframing move.

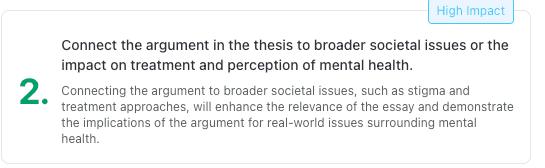

This is also where your stakes should become visible, meaning why the unresolved issue changes interpretation, practice, or the direction of the field.

Example of thesify feedback prompting explicit stakes and real-world implications.

By following this sequence, you ensure that your study is recognized as a necessary extension of the field’s current trajectory rather than an isolated observation.

Failure to ground your aims in a synthesis of existing literature results in a disconnected research gap.

Revision Audit for “Laundry List” Literature Writing

Even with a robust reading base, a literature discussion often collapses into what reviewers recognize instantly as a "laundry list." This issue is rarely about the quality of your sources; rather, it is a structural failure where the relationships between studies remain implicit. A targeted audit helps you edit academic writing so your synthesis is visible and defensible.

Symptoms You Can Spot in 60 Seconds

Scan a single page of your draft and look for these three diagnostic patterns. If you identify two or more, your writing is likely reporting literature rather than synthesizing it.

Repeated Author-Led Openings: Multiple consecutive sentences or paragraphs beginning with names and years (e.g., "Smith (2019) says..."). This signals that your organizing principle is "who wrote what" rather than the debate itself.

One-Study-Per-Sentence Rhythm: Each sentence introduces a new paper in isolation, with no comparison, contrast, or accumulation of ideas. The reader learns individual facts but not the structure of the discourse.

Missing Connective Logic: There is no explicit logical chain. While you do not need to use the word "therefore" repeatedly, you do need visible transitions that signal tension, consequence, or resolution.

Use thesify to ensure you are not just listing sources but applying their core concepts to your research problem.

One Practical Fix: Topic Sentences as Claims About the Debate

The most efficient structural fix is to rewrite your topic sentences so they state a claim about the academic discourse, then place individual studies as evidence within that claim.

Version | Example Construction |

Before (Summary) | "Smith (2019) argues that X. Jones (2020) argues that Y. Patel (2021) finds Z..." |

After (Synthesis) | "Current accounts split on whether X is driven by Mechanism A or Mechanism B, with Smith proposing A and Jones demonstrating evidence consistent with B, while Patel identifies boundary conditions where both appear." |

This "debate-first" approach forces the rest of the paragraph to compare how each key source defines terms, defends assumptions, or limits the scope of prior claims.

Using thesify to Stress-Test Literature Positioning

Once you have restructured your paragraphs, use targeted tools to verify the impact of your revisions:

Example of thesify recommendations that flag common breakdowns in evidence use and interpretation.

For Introductions: Use thesify’s Literature Positioning and Problem Significance checks to ensure your framing matches the discourse you mapped, rather than relying on a generic problem statement.

For Discussions: thesify’s Depth & Coherence feedback lens is particularly useful here; it flags when your writing reads like a restatement of results rather than a high-level integration across studies.

For Rewriting: If you need a focused rewrite loop to generate cleaner comparative phrasing, Chat with Theo is a natural next step once you have your synthesis matrix prepared.

Synthesizing Literature to Position Your Study Clearly

The ultimate objective of synthesizing literature is to ensure your research is recognized as a necessary extension of an established academic conversation. You are not tasked with covering every existing publication; rather, you must map the discourse well enough to justify your study’s entry point.

Success is measured by your ability to answer one question with precision: “Which key academics or seminal studies contributed significantly to this discussion, and what are their main arguments?” When you can articulate this lineage in a few disciplined sentences, your reader immediately understands the stakes of the disagreement and the legitimacy of your contribution.

The Literature Synthesis Workflow

To achieve this level of clarity, follow the repeatable methodology outlined in this guide:

Identify seminal works and key contributors through citation mapping.

Extract each source’s main argument using the extraction template.

Synthesize those arguments into thematic debates using a matrix.

Position your contribution as a refinement, adjudication, or reframing of the discourse.

A successful synthesis results in a logical progression that reviewers—and thesify—recognize as high-impact writing.

Quick Draft Audit in thesify

To stress-test your current literature discussion, upload your draft to thesify. Evaluate whether your writing makes the "key academics and main arguments" visible:

Does the topic sentence name a specific debate or tension?

Do the evidence sentences place 2–4 key sources into that debate by what they argue?

Does the closing sentence state what remains unresolved?

If your feedback indicates that your claims are not sufficiently anchored to the academic discourse you mapped, prioritize restructuring your paragraph logic before refining the prose. This ensures your significance of the study is grounded in evidence rather than assertion.

Try a Free thesify Draft Check

Sign up for thesify for free to audit your positioning and tighten your synthesis. Upload your draft to thesify and check whether you clearly state which key academics shaped the discussion, and what they argue.

Related Posts

Step-by-Step Literature Review Guide with Expert Tips: Learn how literature reviews support research at different academic levels. Get tips on how to synthesize information into a structured argument that justifies your study, develop expertise in academic discourse and theoretical frameworks, and identify research gaps for theses or dissertations. This article guides you through how to conduct a comprehensive literature search using the best academic databases for literature reviews and suggestions for ethical AI tools for literature reviews (research, citation, and analysis).

How to Identify Research Gap for Novelty: A Step-by-Step Guide: Distinguish between a Research Gap (an unanswered question or methodological void) and Research Novelty (the original perspective or solution you provide). Stop wasting time on redundant research. Learn how to identify research gap for novelty with our 2026 framework to ensure your project is original and fundable. Get a checklist for verifying research novelty before submission and lexical bundles for establishing novelty in thesis writing.

Comparative Analysis in Research: Matrix Framework: Comparative analysis in research is a criteria-based evaluation of two or more methods, approaches, theories, or technologies. Instead of summarising sources in parallel, you assess each option against shared standards, make assumptions and boundary conditions explicit, and produce a context-scoped judgement about methodological fit. Learn a PhD-level comparative matrix framework to evaluate methods, tools, or theories using criteria, warrants, and evidence, then write a scoped verdict.