How to Write an Integrative Discussion Chapter for a PhD by Publication

Writing a PhD by publication discussion chapter (sometimes called a thesis by published works) is not about repeating the discussion sections from each paper. Your integrative discussion chapter has a different job: it must synthesise results across papers, explain what your body of work contributes overall, and meet examiner expectations for interpretation, limitations, and implications.

This guide gives you a clear discussion chapter structure, a practical cross-paper synthesis method, and a pitfalls checklist you can use during revision, especially when your studies use different methods, populations, or aims.

If you are still locking down your thesis-level claim, it helps to sanity-check that your overarching argument is explicit and defensible before you start synthesising.

What an Integrative Discussion Chapter Must Do in a Thesis by Publication

In a PhD by publication, your thesis is built from multiple papers that were written for journals, not for a single dissertation narrative. The integrative discussion chapter is where you show how those papers connect, what the combined findings mean, and how the whole project answers your overarching research question. Some university guidelines explicitly describe the need for an integrative discussion that ties the thesis elements together, rather than leaving your readers to infer the connections on their own.

Integrative Discussion Chapter vs Traditional Thesis Discussion

A traditional thesis discussion typically interprets results from one continuous study (or one unified dataset) and develops implications from that single body of work. In a publication-based dissertation, each paper already contains its own discussion, which means your integrative discussion chapter has a different job:

Synthesis across papers: You group findings across studies and interpret patterns, tensions, and boundary conditions at the project level.

No paper-by-paper repetition: You avoid re-stating each paper’s discussion section in sequence, and instead organize around themes, mechanisms, or claims.

Stronger signposting: You add linking logic that helps examiners track how each paper contributes to the overall argument (often using short framing sections and a simple thesis map).

If you want a quick reference point for how “standard” research discussions are typically structured (so you can see what changes in a multi-paper thesis), you can compare against How to Structure a Scientific Research Paper: IMRaD Format Guide. If your discussion is drifting into a paper-by-paper recap, it can help to re-check whether your thesis-level thesis statement is still doing the heavy lifting.

What Examiners Look For in a Publication-Based Dissertation

Examiners tend to reward integrative chapters that read as one sustained argument, rather than a collection of loosely related outputs. A practical way to write toward examiner expectations is to check whether your chapter consistently does the following:

Coherence: The chapter explicitly connects papers to one overarching research question, and clarifies how the studies build on one another.

Project-level contribution: You state what the combined papers add to the field (the “so what” at thesis level), not only at paper level.

Interpretation aligned to evidence: Claims are calibrated to what your studies can support, including uncertainty where needed.

Integrated limitations: You discuss limitations across the whole project (method, sampling, measurement, publication constraints), not only within individual papers.

Clear navigation: Headings, transitions, and brief “linking” paragraphs make it easy to follow the logic across chapters.

Practical Tip for Drafting:

Once you have a working version, run a dedicated revision pass focused only on whether each subsection is:

Making a cross-paper claim

Backing it with evidence from more than one paper.

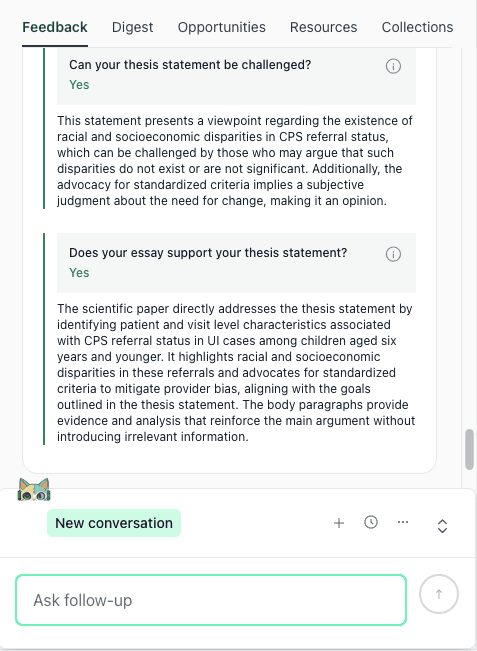

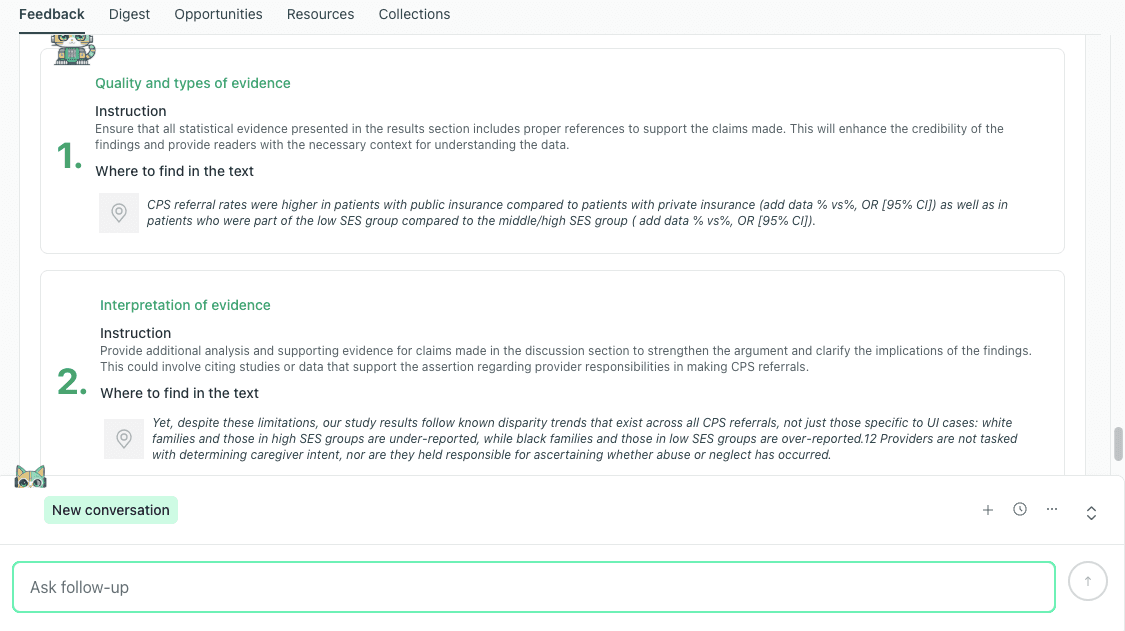

If you want a reliable way to sanity-check interpretation, limitations, and claim strength at the section level, you can use Introducing In-Depth Methods, Results, and Discussion Feedback in thesify.

Plan Your Cross-Paper Synthesis Before You Draft

Before you write the PhD by publication discussion chapter, you need a clear map of how your papers fit together. This planning step prevents a common problem in a multi-study PhD discussion, where you end up summarising Paper 1, then Paper 2, then Paper 3, without making a thesis-level argument.

Start by returning to your overarching research question, then build a simple cross-paper map that shows what each paper contributes. If your overarching research question still feels too broad to synthesise cleanly, revising it first will usually make the discussion chapter much easier to structure.

A quick way to stress-test your thesis-level claim is to ask two questions:

Can this claim be challenged?

Does the combined evidence across your papers actually support it?

Example of a quick thesis-level claim check: is your claim arguable, and does your draft support it across the project?

If you cannot answer “yes” to both in a defensible way, you will feel it later when you try to write synthesis, because the chapter will drift into paper-by-paper recap rather than a project-level argument.

Align Your Papers to the Overarching Research Question

A fast way to do this is to create a matrix that links each paper to the thesis-level aims and key findings. This makes cross-paper synthesis easier later, because you can see overlap, gaps, and points of tension at a glance.

Use a “Papers-to-Aims” matrix:

Paper | Thesis Aim / Sub-Question | Method / Data | Key Finding(s) | Contribution to Thesis Claim |

Paper 1 | ||||

Paper 2 | ||||

Paper 3 |

How to use it (quick method):

Fill in Thesis Aim / Sub-Question first, then check that each paper genuinely answers part of it.

Write Key Finding(s) as one sentence per paper, not a paragraph.

Populate Contribution to Thesis Claim with the thesis-level takeaway (what that finding lets you argue, cautiously). If you are struggling to write the ‘Thesis Aim / Sub-Question’ column precisely, treat each aim as a testable claim and tighten it before you move on.

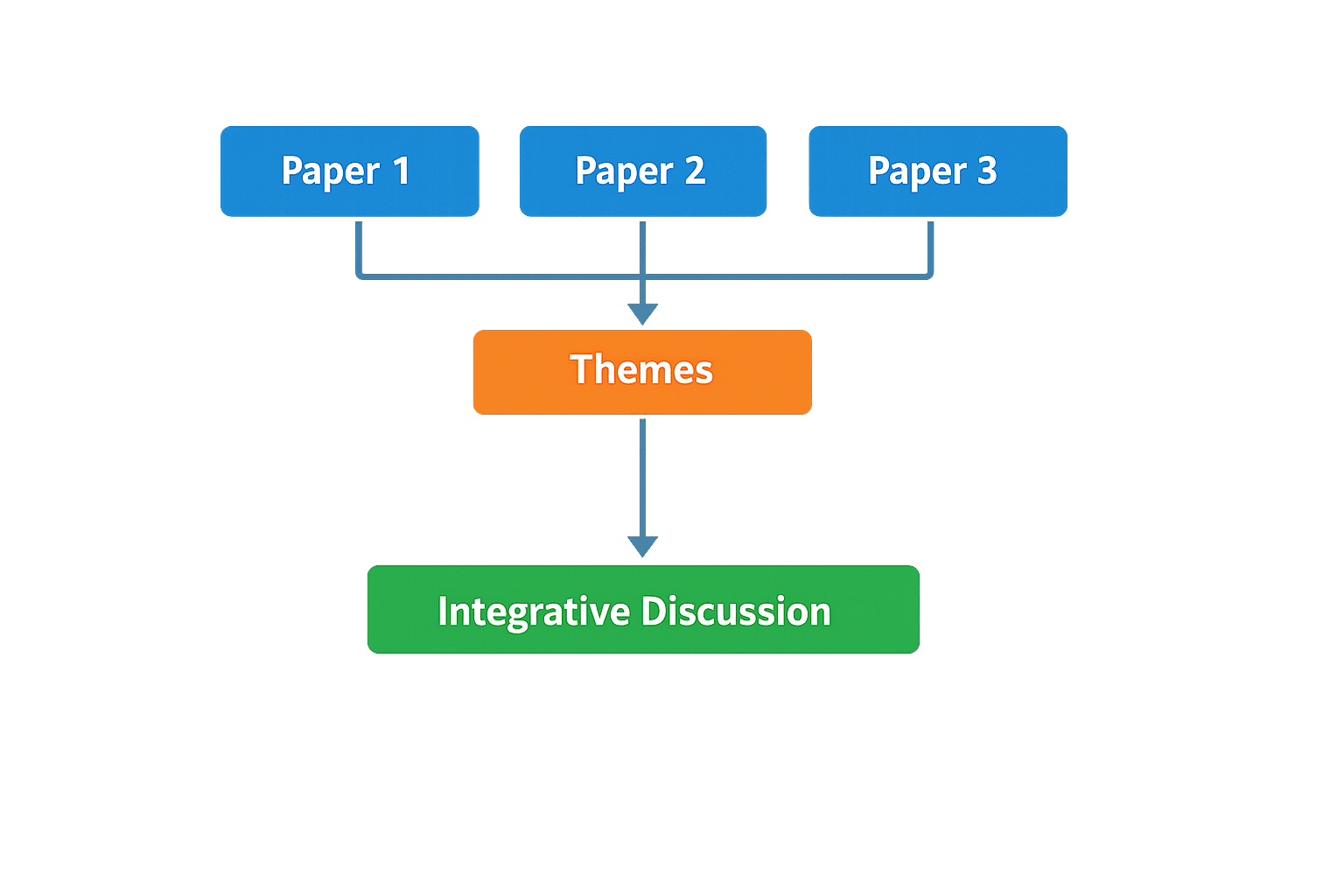

A simple cross-paper synthesis workflow: group findings from each paper into shared themes, then write the integrative discussion around those themes.

Build Themes With a Thematic Synthesis Framework

Once your matrix is complete, move from “paper-level” thinking to “theme-level” thinking. A thematic synthesis framework helps you group related findings across papers into a small number of thesis-level themes (often 3–6), for example:

mechanisms or processes (what explains the effect)

population differences (who benefits, when, under what conditions)

methodological insights (what your methods allow you to claim)

theoretical contributions (how your findings support, revise, or challenge theory)

Examiners tend to respond well when themes are explicit and justified because it demonstrates coherence and control of the argument. Your aim is to interpret patterns across the project, not to restate each paper’s discussion. If you are unsure whether a theme is specific enough, check whether you can point to concrete evidence from more than one paper that supports it.

Create a synthesis table:

Theme (Thesis Level) | Paper 1 Evidence | Paper 2 Evidence | Paper 3 Evidence | What You Can Conclude (Calibrated Claim) |

Theme A | ||||

Theme B | ||||

Theme C |

Tip: Write the final column (“What You Can Conclude”) in careful, evidence-aligned language. You can later convert those sentences into your discussion subheadings.

If you are still deciding how to frame your overarching claim, it can help to clarify which theoretical lens you are using and why. See How to Use Theory in Academic Papers for a practical way to align theory, claims, and evidence before drafting.

Integrate Different Methods and Disciplines Without Losing Coherence

If your thesis includes different methods (for example, qualitative interviews in one paper and quantitative modelling in another), synthesis is still possible, but you may need a two-step structure:

Within-method synthesis: briefly interpret patterns within qualitative papers together, then within quantitative papers together.

Cross-method integration: explain what you learn when you put those interpretations side by side (agreement, contradiction, boundary conditions).

This prevents you from forcing incompatible results into one theme too early, and it helps you explain differences in what each method can support. If your work spans disciplines, remember that conventions for evidence, argument structure, and claims vary across fields. You can reference Understanding Differences in Academic Writing Across Disciplines when you explain why methods, terminology, or standards of proof differ across your papers.

Brainstorming Questions for Cross-Paper Synthesis |

Use these questions to generate themes that are thesis-level (not paper-level): • What is the single best one-sentence answer to your overarching research question, based on all papers? • Which findings repeat across papers, and what do those repetitions suggest? • Where do findings diverge, and is the divergence methodological, contextual, or theoretical? • What claim can you support using evidence from at least two papers? • What is the strongest limitation that applies across the whole project (not just one study)? • What would you say is your project’s contribution if you had only 60 seconds to explain it? |

Integrative Discussion Chapter Structure for a PhD by Publication

A clear structure helps your reader follow your argument across multiple studies. In a PhD by publication, the goal is not to repeat the discussion section from each paper. It is to bring the papers together into a single interpretation that answers your overarching research question.

Most integrative discussion chapters can be organized into five elements. You can use these as major subsections, or as a checklist to confirm your draft is complete:

Summary of key findings (thesis level)

Interpretation and cross-paper synthesis (theme level)

Implications and contributions (field level)

Limitations and future research (project level)

Recommendations and practical applications (evidence level)

Integrative Discussion Chapter Checklist

☐ Summary of key findings (thesis level) | A cohesive snapshot of what the papers show together |

☐ Interpretation and cross-paper synthesis (theme level) | Patterns, contrasts, and explanations organized by theme |

☐ Implications and contributions (field level) | What your combined findings add to theory and practice |

☐ Limitations and future research (project level) | Limits that apply across the project, plus next steps |

☐ Recommendations and practical applications (evidence level) | Practical takeaways that follow from your evidence |

Start With a Thesis-Level Summary of Key Findings

Open with a short paragraph that restates your overarching research question, then summarises the key findings across all papers in one cohesive snapshot. This summary should be thesis-level, not paper-by-paper.

Practical approach:

Write 3–5 sentences total, each sentence capturing a major finding that cuts across papers.

Use your synthesis table to avoid re-stating paper-specific detail.

Signal what the rest of the chapter will do (for example, “The next sections synthesise these findings across three themes…”).

If your summary starts to drift into background or methods detail, re-check that you are still answering the thesis-level question directly.

This move sets up the rest of the chapter and reduces repetition later, because you have already stated the thesis-level story.

Write Interpretation Sections by Theme, Not by Paper

This is the core of an integrative discussion chapter. Instead of organizing your discussion as “Paper 1,” “Paper 2,” and “Paper 3,” use thematic subheadings that reflect the claims you can make across the whole project.

For each theme, focus on:

the pattern across papers (agreement, partial agreement, divergence)

a plausible explanation (method, context, population, theory)

what that pattern means for the overarching research question

Cross-Paper Synthesis Table

Paper 1 Evidence | Paper 2 Evidence | Paper 3 Evidence | Thesis-Level Interpretation | Boundary Conditions | |

Theme 1: | |||||

Theme 2: | |||||

Theme 3: |

State Thesis-Level Contributions and Implications

After you interpret the themes, make your contribution explicit. A strong integrative chapter clarifies what the thesis adds that individual papers do not show on their own.

Cover implications at two levels:

Theoretical implications, what your synthesis supports, refines, or challenges in the literature

Practical implications, what your combined evidence suggests for policy, practice, or decision-making (when relevant)

A useful drafting check is to write one paragraph that starts with: “Taken together, these studies show…” then specify what is new at the thesis level, and what remains uncertain.

Discuss Limitations Across the Whole Project

Limitations in a publication-based thesis are often distributed across studies. Your job is to surface the thesis-level limitations that affect how far you can take your conclusions.

Group limitations by theme rather than by paper, for example:

sample and setting constraints that recur across studies

measurement or operationalisation differences across papers

methodological trade-offs (especially in mixed methods)

publication constraints (timelines, journal formatting, space limits)

Then move directly into future research that responds to those limitations. This keeps the section constructive and focused.

End With Recommendations Grounded in Evidence

If recommendations make sense for your field, keep them tightly linked to what your synthesis supports. Avoid recommendations that require evidence you do not have.

To keep recommendations evidence-aligned:

tie each recommendation to a specific theme or limitation

use calibrated language (“suggests,” “may,” “is consistent with”)

name boundaries (“This applies in contexts similar to…”)

When you revise, do one dedicated pass focused only on claim strength and evidence alignment. If you want a structured way to check interpretation, limitations, and overclaiming at the section level, you can use Introducing In-Depth Methods, Results, and Discussion Feedback in thesify.

Meeting Examiner Expectations and Avoiding Common Pitfalls

In a PhD by publication, examiners are rarely judging your papers in isolation. They are judging whether your thesis reads as a coherent, original body of work with a clear contribution that you can credibly claim as your own.

A strong integrative discussion chapter makes your logic easy to follow, states your thesis-level contribution explicitly, and shows careful boundaries around what your evidence can and cannot support.

Demonstrating Coherence and Contribution Across Papers

Coherence is not only about writing style, it is about whether your reader can track how the papers connect to a single research question and to one another. You can support coherence by using linking text, consistent terminology, and a clear “thesis map” that explains how the studies build across the project.

Ways to make coherence visible:

Use short linking paragraphs between themes or papers that explain why the next section follows.

Keep key terms consistent, and define them once at thesis level if papers use different labels.

Briefly signpost how each paper contributes to the overarching argument (what it adds, and what it does not add).

A strong integrative discussion also states your contribution without forcing the examiner to infer it. If your papers already include contributions, restate them at thesis level and explain what becomes visible only when the findings are synthesised.

You can adapt the template below as a contribution statement:

Contribution Statement Template |

Taken together, these studies show that [main thesis-level finding]. Across the papers, the evidence suggests [pattern or mechanism], particularly in [context/population]. This thesis contributes [theoretical contribution] by [how it advances, clarifies, or challenges existing work], and contributes [practical contribution] by [implication for practice/policy/decision-making]. At the same time, the findings are bounded by [main limitation or uncertainty], so conclusions should be interpreted as [calibrated claim] rather than [overstated claim]. |

Common Pitfalls Checklist |

Repeating each paper’s discussion section: turns the chapter into a recap, rather than a thesis-level interpretation across studies. |

Listing papers sequentially (Paper 1, Paper 2, Paper 3): hides patterns and makes it harder to see the overarching argument. |

Overclaiming: states conclusions that the combined evidence cannot support, or ignores uncertainty and boundary conditions. A useful revision habit is to mark each claim that uses strong verbs (prove, show, demonstrate) and verify you can point to specific results supporting it. |

Ignoring inconsistencies or contradictions: skips differences across methods, samples, or contexts, instead of explaining what they mean. |

Failing to integrate different methods: presents qualitative and quantitative results as separate narratives without explaining how they jointly answer the research question. For guidance on how conventions differ by field, see Understanding Differences in Academic Writing Across Disciplines. |

Neglecting limitations at thesis level: discusses limitations only within individual papers, without identifying constraints that apply across the whole project. |

A common reason integrative discussion chapters read “thin” is that they repeat what the papers already said without adding project-level analysis. Two high-frequency failure modes are:

1. Claims that are not supported by evidence

2. Restating a claim rather than interpreting it.

Two frequent discussion problems to fix during revision: unsupported claims and summary that replaces analysis.

When you revise, highlight every sentence that asserts popularity, causality, effectiveness, or mechanism, then check whether you provide direct support from your results (across more than one paper where possible), or clearly label it as a hypothesis.

Authorship and Multi-Author Papers

Examiners often look for clarity on what you did, especially when papers are co-authored. You can address this directly by providing a simple authorship attribution table that shows your role across conceptualisation, data collection, analysis, and writing. This keeps the discussion chapter focused on synthesis while still giving examiners the transparency they need.

Authorship Attribution Table (Template)

Paper | Co-Authors | Your Role (1–2 Lines) | Key Tasks You Led | Notes on Contribution |

Paper 1 | ||||

Paper 2 | ||||

Paper 3 |

If your institution requests a specific format for author contributions, use their wording, and keep your descriptions factual and consistent across papers. The goal is to make your contribution easy to assess, without defensiveness or excessive detail.

If you used AI tools during drafting, check your institution’s disclosure expectations so your writing process stays compliant.

Practical Workflow for Drafting and Revising an Integrative Discussion Chapter

A structured workflow keeps the integrative discussion chapter manageable, especially in a PhD by publication where you are synthesising across multiple papers. The aim is to move from thesis-level planning, to cross-paper synthesis, to drafting, then to revision passes that improve coherence and reduce repetition.

Step-by-Step Workflow for Drafting

Revisit your overarching research question and aims, and write a one-sentence thesis-level answer you are working toward.

Map each paper to your aims, so you can see what each paper contributes to the overall argument.

Brainstorm themes that cut across papers (patterns, mechanisms, boundary conditions, or contexts).

Create a synthesis table that shows which papers support each theme, and what you can credibly conclude at thesis level.

Draft a short thesis-level summary of key findings, focusing on what the papers show together.

Draft the interpretation section using thematic sub-sections, and explain patterns, contradictions, and explanations across papers.

Draft implications, limitations, and recommendations at thesis level, not paper level.

Revise for coherence, check transitions, align terminology, and remove any paper-by-paper repetition.

Get feedback from supervisors, peers, or writing support, with a focus on coherence and claim strength.

Integrate feedback, tighten language, and do a final pass for evidence alignment, limitations, and clarity. If you keep delaying the integrative discussion because it feels cognitively heavy, a short, scheduled drafting routine is often more effective than waiting for a perfect free day.

If your argument still feels fragmented during drafting, it often helps to re-check the theoretical lens you are using to frame the synthesis. See How to Use Theory in Academic Papers for a practical way to align theory, claims, and evidence.

Using Visual Aids and Tables to Support Cross-Paper Synthesis

Visual aids can make a multi-study PhD discussion easier to follow because they show connections that are hard to communicate in paragraphs alone. If you include a synthesis table or figure, do a final check for labeling, caption clarity, and whether the figure is referenced in the surrounding text. A simple flowchart can illustrate how each paper feeds into shared themes, and a checklist can confirm you have covered each element of the discussion chapter.

Example: Findings-to-Themes Table | What You Can Say at Thesis Level |

Theme: Consistent pattern across papers | The combined evidence supports a stable pattern across contexts, within the limits of the samples studied. |

Theme: Divergent results across papers | Differences may reflect variation in methods, settings, or populations, which suggests boundary conditions rather than a single universal effect. |

Theme: Mechanism or explanation emerging across studies | When findings are synthesised, a plausible mechanism becomes visible that is not fully apparent in any single paper. |

Seeking Feedback and Using Tools During Revision

Feedback is most useful when you ask for specific checks, rather than general impressions. For an integrative discussion chapter, the highest-impact feedback questions usually target coherence, synthesis, and claim strength.

You can ask reviewers to focus on:

whether the chapter reads as one sustained argument

whether each theme is supported by evidence from more than one paper

whether contradictions are acknowledged and interpreted, rather than ignored

whether limitations and implications are stated at thesis level

whether claims are calibrated to what the evidence supports

If feedback comes back inconsistent or conflicting, prioritise changes that affect coherence and claim strength before you polish wording.

Once you have incorporated human feedback, a targeted tool-based review can help you catch issues that are easy to miss late in the drafting process (for example, unsupported claims, missing limitations, or weak interpretation).

Example of revision targets in an integrative discussion chapter: evidence quality checks and interpretation checks, with pointers to where issues appear in the draft.

If you want structured feedback on interpretation, limitations, and section clarity, you can use Introducing In-Depth Methods, Results, and Discussion Feedback in thesify to review your discussion alongside the methods and results in the same thesis workflow.

Troubleshooting an Integrative Discussion Chapter in a PhD by Publication

Not every PhD by publication follows a neat, linear story. Publication-based theses often include mixed methods, evolving aims, shifting variables, or findings that do not align perfectly across studies. This section gives you practical language and structure options you can use when your papers are difficult to integrate.

If you are stuck, start with these prompts:

A fast way to diagnose gaps in a draft: confirm you can answer objective, key findings, and implications at thesis level.

If you are unsure what is still missing, run a final “coverage check” using a small set of direct prompts. At minimum, you should be able to answer:

What the project objective was

What the key findings were across the full set of papers

What implications follow from the combined evidence.

If any of those answers feels vague, that is usually a sign your chapter needs clearer thesis-level signposting and tighter synthesis.

Common Problems in a Thesis by Publication Discussion Chapter | Practical Response |

Your papers use different methods or disciplines | Synthesize within each method or discipline first, then add a short integration subsection that explains what changes when you interpret the strands together. |

Your papers have different aims, variables, or outcomes | Write an explicit “linking logic” paragraph that shows how each paper answers a different part of the overarching question, then synthesise at the level of mechanism, context, or contribution. |

Your findings conflict across papers | Treat the conflict as a boundary condition, compare contexts and methods, explain robustness, then propose targeted follow-up research. |

One or more papers are not yet published | Synthesize what is fully reportable, label in-press or under-review work clearly, and avoid building core claims on results that are not documented in full. |

When Your Papers Use Different Methods or Disciplines

If your thesis includes different methods (for example, qualitative interviews in one paper and quantitative modelling in another), the risk is that your discussion becomes two separate narratives. A reliable structure is a two-stage synthesis:

Synthesis within method or discipline (what the qualitative papers show together, what the quantitative papers show together)

Cross-paper integration (what becomes visible when you interpret both strands side by side)

This approach keeps the discussion fair to each method and prevents you from forcing incompatible forms of evidence into one claim too early.

Example Phrasing for Mixed Methods Integration |

“Because the included studies use different methods, I first synthesise the qualitative findings to clarify mechanisms and lived experience, then synthesise the quantitative findings to assess patterns and associations. I then integrate both strands to identify where they converge, where they diverge, and what that implies for the overarching research question.” |

When Your Papers Have Different Aims, Variables, or Outcomes

In many publication-based dissertations, the papers are not designed as perfect replications. One paper might focus on explaining a mechanism, another might test an association, and a third might evaluate an intervention or describe a subgroup. When aims or variables differ, synthesis is still possible, but it has to happen at the right level.

A practical approach is:

clarify the overarching research question at thesis level

name the role of each paper in answering part of that question

synthesise across papers using a shared logic, such as mechanism, context, or contribution, rather than forcing the same outcome language across all studies

Linking Logic Template (Different Aims Across Papers) |

“Although the papers address different aims, they contribute to the same overarching research question by answering complementary sub-questions. Paper 1 establishes [what it establishes], which provides the basis for Paper 2’s analysis of [what it tests]. Paper 3 extends this by examining [what it extends] in [context/population]. Synthesised together, these studies support the thesis-level claim that [main claim], while also showing that the claim is conditional on [boundary condition].” |

If your studies sit across different disciplinary conventions (including differences in what counts as evidence or how claims are framed), you can use Understanding Differences in Academic Writing Across Disciplines as a reference point when you explain why methods, terminology, or standards of proof vary across papers.

When Findings Contradict Across Papers

Contradictory findings are not automatically a weakness. In an integrative discussion chapter, they often signal boundary conditions, context effects, measurement differences, or analytic choices that are not visible within a single paper.

A practical way to write this section is to:

state the contradiction clearly

compare contexts and methods (population, setting, measures, time frame, analytic choices)

explain which finding appears more robust and why (for example, stronger design, better measurement, larger sample, triangulation)

propose follow-up work that would resolve the tension

Example Phrasing for Contradictory Findings |

“Across the papers, the results do not align fully. One plausible explanation is that the studies differ in [context/population/measurement], which may moderate the relationship observed. This suggests the effect is conditional on [boundary condition], rather than uniform across settings. Future research should test this directly by [specific design change or additional measurement].” |

When Papers Are Not Yet Published at Submission

In some theses by publication, one paper may be accepted but not yet in print, or still under review at the time you submit. The safest approach is to synthesise the studies you can document in full, and treat in-press or forthcoming work as clearly labelled context rather than a primary pillar of your argument.

If you refer to not-yet-published work, keep it factual and bounded:

label the status clearly (submitted, under review, accepted, in press)

summarise only what you can substantiate in the thesis materials

use appendices for supporting material if your institution permits it

If you are still navigating review cycles or planning where to send related manuscripts, it helps to understand what happens after submission and what ‘peer review’ typically requires.

Sample Paragraph Integrating Findings Across Two Papers

Taken together, Papers 1 and 2 suggest that the intervention is associated with improved outcomes, but the strength of the effect depends on context. Paper 1 reports consistent improvement in the primary outcome in a supervised setting, while Paper 2 finds smaller and more variable gains in a self-directed setting. One plausible interpretation is that structured support changes how participants engage with the intervention, which could explain why effects attenuate when guidance is removed. This synthesis suggests the intervention may be effective under conditions of sustained support, but less reliable when delivery is fully self-managed. Future studies should test this boundary condition directly by comparing delivery modes while holding dosage constant.

FAQs: PhD by Publication Discussion Chapter

What Is an Integrative Discussion Chapter in a Thesis by Publication?

An integrative discussion chapter is the thesis-level discussion in a PhD by publication (or thesis by publication). It synthesises findings across multiple papers to answer one overarching research question, rather than repeating each paper’s discussion.

How Do You Structure the Discussion Chapter of a PhD by Publication?

A common structure for a PhD by publication discussion chapter includes:

Summary of key findings across all papers

Interpretation and cross-paper synthesis organized by themes

Thesis-level contributions and implications

Limitations across the whole project and future research directions

Recommendations or practical applications (when relevant)

How Can I Synthesise Findings Across Multiple Papers?

Start by mapping each paper to your thesis aims, then group findings into 3–6 themes that cut across studies (for example, mechanisms, contexts, or boundary conditions). Use a synthesis table to track which papers support each theme, then write your interpretation around themes instead of papers.

What Do Examiners Expect in the Discussion Chapter of a Publication-Based PhD?

Examiners typically look for:

A coherent argument that connects all papers to one research question

Clear thesis-level contribution and originality

Interpretation that matches the evidence, including uncertainty where needed

Limitations and boundary conditions discussed across the whole project

Signposting that makes the thesis easy to follow, especially across studies

If you are unsure which issues to address first, a pre-submission-style check can help you prioritise coherence and claim strength.

How Do I Avoid Repeating the Discussion Sections of Individual Papers?

Avoid a paper-by-paper recap. Instead, write a short thesis-level summary of key findings, then organise the chapter by themes. For each theme, integrate evidence from more than one paper where possible, and focus on what the combined results mean.

What Should I Write If My Papers Use Different Methods?

Use a two-stage structure. First, synthesise findings within each method (for example, qualitative papers together, quantitative papers together). Then add an integration subsection that explains where the strands converge or diverge, and what that implies for the overarching research question.

How Do I Address Contradictions Between Papers in the Discussion Chapter?

Treat contradictions as part of the interpretation. State the difference clearly, compare contexts and methods (sample, setting, measures, analysis), and explain which result appears more robust and why. Then propose targeted future research that would resolve the tension.

Where Should I Discuss Limitations and Future Research in a Multi-Study Thesis?

Include limitations and future research at thesis level, not only within the individual papers. Group limitations that apply across studies (methods, sampling, measurement, publication constraints), then link each limitation to a specific future research direction.

Finish Your PhD by Publication Discussion Chapter

Your PhD by publication discussion chapter is where separate papers become one coherent thesis argument. When you synthesise findings across papers, organize interpretation by themes, and state thesis-level implications and limitations, you make it easier for examiners to see your contribution and evaluate your reasoning.

If you are close to a full draft, focus your effort on revision passes that improve clarity and coherence:

Re-check that your opening summary answers the overarching research question in thesis-level language.

Confirm your subheadings are theme-based, not paper-based.

Make sure each major claim is supported by the relevant evidence, and that uncertainty and boundary conditions are stated where needed.

Consolidate limitations that apply across the whole project, then link each limitation to a specific future research direction.

Do a final read-through for repetition, especially where your integrative discussion starts to sound like individual paper discussions.

If you want a final coherence pass before submission, you can follow a chapter-by-chapter revision workflow that focuses on coherence, evidence alignment, and missing components.

Sign Up for thesify for Free

If you want a simple way to review your draft before submission, you can sign up for thesify for free and use it to check clarity, coherence, and whether your discussion claims stay aligned with your evidence.

Related Posts

How to Improve Your Thesis Chapters: 7-Step AI Feedback Guide: Learn a 7-step revision process and AI feedback guide to improve your thesis chapter. This guide’s revision plan is best for academics interested in a structured approach that ties theory into practice. It addresses academic rigor at the core by ensuring your thesis statement (or main research question/central argument) is solid. Find out how to eliminate awkward phrasing and polish your tone using academic writing AI assistance. Plus, get a thesis proofreading checklist and final steps before submitting thesis checklist.

Overcome Thesis Procrastination & Finish Your Thesis on Time: Struggling with thesis procrastination? Discover effective strategies to stay motivated, meet your deadlines, and use AI tools like thesify to finish your thesis on time. In the end, overcoming thesis procrastination is less about willpower and more about structure, support, and steady progress. By drafting an outline, writing consistently, using AI tools responsibly, seeking feedback, and polishing with care, you position yourself for real thesis writing success

How to Get Table and Figure Feedback for Your Scientific Paper: Peer review feedback on visuals is often accurate but underspecified. When someone writes “unclear figure” or “table is not well integrated,” you still have to diagnose the cause, decide what to change, and translate that into a revision plan your co-authors can execute. Learn to improve tables and figures in your manuscript. This guide shows how thesify provides structured feedback, exportable reports and co-author collaboration.