AI Proofreading Tools for Academic Writing: Are They Worth It?

Built-in proofing tools in Word and Google Docs catch basic errors, but are they enough when you are drafting a thesis or journal article? Or do you need a dedicated AI proofreading tool to produce polished research writing?

This article examines the strengths and weaknesses of built-in grammar checkers versus third-party AI proofreading tools for academic writing, drawing on empirical studies and surveys to help you decide if external tools are necessary for your own workflow.

The goal is not to rank “the best grammar checker for academic writing”, but to help you make a clear decision about whether you need tools beyond the ones already built into your writing environment.

Why Proofreading Matters in Academic Research Writing

Reviewers, editors, and examiners often form an opinion about your work within the first few paragraphs. Repeated spelling errors, inconsistent grammar, or awkward phrasing can make even strong results look careless. That is why many researchers now ask a practical question:

If Word or Google Docs already offers spelling and grammar checks, do you really need extra AI proofreading tools for academic writing?

Built‑In Grammar Checkers: Features and Limitations

Built-in spelling and grammar checkers are now standard in most writing environments. Microsoft Word Editor, Google Docs grammar check, and Apple’s system-level spell-checker all aim to catch frequent errors without requiring you to install anything.

These tools matter because they form the baseline. To decide whether you need additional AI proofreading tools for academic writing, you first need a realistic picture of what you already have.

Spelling and Grammar in Microsoft Word and Google Docs

Built-in checkers in Word, Google Docs, and Apple’s ecosystem provide a baseline:

Spelling correction for most common words

Basic grammar checks, such as simple subject–verb agreement and missing articles

Basic punctuation support, such as missing periods or duplicated spaces

For routine tasks such as email, short feedback, meeting notes, or early idea dumps, these tools already prevent many distracting errors. They are integrated into your workflow, run locally in many cases and require no extra setup.

Style Suggestions and Language Support in Built-In Tools

Recent versions of Word and Google Docs offer style and clarity suggestions. These may include:

Recommendations to shorten long sentences

Flags for passive voice or weak phrasing

Suggestions to replace vague words with more specific ones

Some inclusive-language issues

Microsoft Editor goes further by offering “refinement options” for clarity, conciseness, and formality. Google Docs, meanwhile, offers automatic suggestions for inclusive language and tone.

Where Built‑In Proof-Reading Tools Fall Short

These features are useful, but you should treat them as basic writing aids, not full editing. Even relatively advanced grammar engines struggle with complex syntax, optional constructions, and discipline-specific usage. Thus, built‑in grammar checkers have notable reported concerns for scholarly writing: Several limitations matter for academics:

Discipline-specific style may be misinterpreted: default suggestions may inadvertently “simplify” technical language or discourage passive constructions that are standard in certain disciplines. Built‑in tools may misinterpret field-specific terminology, equations and citation formats.

Inclusive-language checks are incomplete: biased or exclusionary terms may not be flagged, and some neutral phrases are marked inappropriately.

Multilingual support is uneven: built-in tools support many languages but vary in quality; they may struggle when you draft in one language and quote in another.

Low detection rates for complex errors: Tools built on rule-based engines such as LanguageTool can flag a useful subset of surface-level errors, yet their error counts correlate only moderately with human judgments of writing quality.

Limited correction of nuanced grammar: Built-in tools rarely handle hedging, modality or other nuanced grammar choices well, and suggestions may oversimplify careful academic phrasing.

For researchers drafting theses or journal articles, these gaps mean built‑in checkers alone rarely suffice.

What Built-In Grammar Checkers in Word and Google Docs Can and Cannot Do

From an academic perspective, built-in tools act as a coarse filter. They are useful for quick clean-up of drafts, but they do not provide a context-aware review of argumentation, discipline-specific terminology, or nuanced style

For academic manuscripts, that means:

Spelling is usually handled well by built-in tools, especially once you add your own technical terms to the dictionary.

Grammar and punctuation are handled reasonably for short, straightforward sentences, but complex syntax, heavy nominalizations and hedged claims will often pass unchecked or receive unhelpful suggestions.

Style and readability suggestions are generic and not tuned to disciplinary expectations or journal guidelines.

In other words, if you rely only on Word or Google Docs, you will probably catch most typos and some obvious grammar issues. You are less likely to see systematic feedback on longer, more intricate sentences, which are exactly where many doctoral writers struggle.

From an academic-writing perspective, built-in checkers are a baseline safety net, not a full proofreading solution.

How AI Proofreading Tools for Academic Writing Compare to Built-In Checkers

The market now includes many AI proofreading tools for academic writing. Tools like Grammarly, Paperpal, Trinka, and Writefull are often marketed as the “best grammar checker for academic writing”. The real question is more modest: do these tools provide measurable benefits beyond Word and Google Docs for academic texts?

Accuracy of AI Proofreading Tools for Research Papers and Theses

Third-party AI proofreading tools position themselves as more powerful than the default checkers in Word or Google Docs. The evidence here is more nuanced than marketing claims suggest.

Studies in applied linguistics and writing research show that:

Proofreading tools for research papers and theses reduce surface errors.

Classroom and quasi-experimental studies with university EFL students report fewer grammar, vocabulary and mechanics errors when drafts are revised with online grammar checkers such as Grammarly or SpellCheckPlus, compared with self-editing or teacher feedback alone.

2. Gains are strongest for lower-proficiency and non-native writers.

Yang’s study of SpellCheckPlus in the Korean Journal of English Language and Linguistics found that feedback from the online grammar checker improved grammar accuracy and was especially useful for lower-proficiency L2 learners. A LEARN Journal study on Thai undergraduates using an online grammar checker similarly focused on reducing syntactic errors rather than higher-level organization.

Automated feedback does not fix higher-level academic writing problems.

Across these studies, online grammar checkers help with sentence-level accuracy but have little effect on argument structure, coherence, or disciplinary positioning, so they cannot replace human feedback on research design or rhetorical choices.

False positives remain a concern in expert texts.

A 2024 Heliyon evaluation of Grammarly on articles from Q1 linguistics journals found that the tool frequently over-flagged acceptable academic usage as errors, leading the authors to conclude that Grammarly is not reliable as a stand-alone assessor of academic English.

These results explain why questions like “Is Grammarly worth it for academic writing?” or “Do I need Grammarly if I have Google Docs?” are so common. External tools reliably catch additional errors that built-in systems miss, especially in categories like prepositions, article use and some kinds of agreement. They do not, however, function as fully reliable proofreaders for research papers.

For you as a researcher, this means:

If you are a non-native English academic or know you make frequent grammar and mechanics mistakes, adding an AI proofreading tool for researchers can meaningfully reduce residual surface errors in theses, journal articles and grant proposals, especially when combined with your own revision.

If your main issues are clarity of argument, structure or contribution, AI proofreading tools will not replace supervision, peer review, or careful redrafting.

Whatever tool you choose, you still need to read every suggestion critically, especially in dense technical sections, because even the best grammar checker for academic writing can misinterpret disciplinary conventions, and optional academic style.

Handling Citations and Technical Vocabulary in Academic Texts

Academic texts introduce features that are inherently difficult for automated grammar checking:

Parenthetical and bracketed citations that break up sentences

Field-specific acronyms, Latin terms and formulaic expressions

Equations, code fragments and inline symbols

General-purpose AI proofreading tools allow custom dictionaries and provide “academic” or “technical” style options, yet they still:

Mislabel correct technical terms as errors

Suggest replacements that weaken terminological precision

Treat citation patterns as grammatical problems

Some academic proofreading software, including tools built around journal submission workflows, attempts to account for this by ignoring citations or LaTeX markup. Even so, these systems work on surface patterns, not disciplinary understanding. You still need to make the final judgement on any change that touches specialized terminology or citation structure.

User Experience, Costs and Data Practices in Academic Proofreading Software

Compared with built-in checkers, external AI proof-reading tools differ along three dimensions that matter for researchers:

Integration and convenience: plug-ins for Word, Google Docs and browsers make it easy to run checks across multiple platforms and file types.

Cost: the most capable versions usually require subscriptions. Free tiers typically limit document length or hide advanced features.

Data handling: many tools send text to remote servers for analysis. Some providers explicitly acknowledge that user content may be used to train or improve their models, while others stress that user text is not used for training or is only stored briefly.

For academics, these trade-offs are not trivial. Additional error detection and convenient integrations are useful, but they must be weighed against subscription costs and the implications of sending unpublished work to third-party servers.

Curious how to assess whether an AI tool is “actually academic”? Check out Criteria to Identify Academic-Grade Tools.

Academic Proofreading Software and the Specific Needs of Researchers

The value of AI proofreading tools for academic writing depends heavily on who is using them and what kind of academic texts they are working on.

Grammar Checkers for Non-Native English Academics

Non-native English writers often face overlapping challenges:

Complex grammar and word order

Limited access to idiomatic expressions in their field

Pressure to meet reviewers’ expectations for “native-like” academic English

Several studies in English-as-a-foreign-language contexts suggest that grammar checkers can help some academics but not all:

A 2024 study with Thai undergraduates found that using an online grammar checker reduced syntactic errors and increased students’ confidence, although gains varied between English majors and students in “English for Careers” programs. A 2024 study suggests that grammar checkers may misidentify syntactic errors for more advanced writers.

Other work comparing online grammar checkers and self-editing argue that tools are most helpful when students still receive explicit instruction and are encouraged to reflect on errors, rather than simply accepting suggestions.

For non-native academics, this suggests that AI proofreading tools for researchers can be particularly useful to:

Identify recurring patterns that you may not notice during self-editing

Provide immediate feedback when human readers are unavailable

Reduce cognitive load during the final proofreading phase

However, these tools do not replace the need to understand grammar rules, to read widely in your discipline, and to learn typical phrasing for methods, results and discussion sections.

Academic Voice, Argumentation and Over-Editing

Academic voice reflects how you position yourself in relation to prior work, how cautiously you phrase claims and how you build argumentation. Automated suggestions are not calibrated to your theoretical framework or disciplinary debates.

A 2021 systematic review of automated grammar checking in English language learning cautions that over-reliance on tools can interfere with learning to self-edit, and can gradually flatten stylistic variation.

Guidance from academic writing experts and ethics-oriented AI resources emphasizes that you should:

Use AI tools to improve clarity at the sentence level, not to generate or restructure arguments.

Treat any substantial rephrasing as a draft that you must check carefully against your intended meaning.

Maintain control of hedging, modality and emphasis, since these signal your evidential standards and disciplinary norms.

A reasonable rule of thumb is that if you would not be comfortable explaining a suggested change to a supervisor or co-author, you probably should not accept it.

Privacy, Bias, and Ethical AI Use in Academic Writing

External academic proofreading software also raises questions about privacy, fairness and academic integrity, which affect whether these tools are appropriate in your context.

Proofreading Tools that Protect Data Privacy

Many AI proofreading tools rely on cloud infrastructure. This can pose real risks for researchers working with:

Unpublished findings

Confidential qualitative data

Sensitive policy or industry reports

A recent meta summary on AI in higher education highlights data privacy and security as major concerns for both students and faculty. At the same time, industry discussions caution that generic AI tools may store prompts, use them for training or expose them through system errors if not configured correctly.

For academics, good practice includes:

Checking whether a tool stores user text and whether it is used for training

Using privacy-protecting modes where available, or institutionally provisioned tools with clear guarantees

Avoiding uploads of identifiable human-subject data or proprietary information

If data privacy is a strict constraint, it may be safer to limit yourself to built-in spelling and grammar in local documents, even if that means accepting a higher manual proofreading burden.

Bias, Dialects, and Fairness in Grammar Checkers

Bias in language models and bias-checking features is an active research topic. A study of large language models shows that they can reproduce harmful stereotypes when prompted with linguistically biased input. There is also concern that mainstream systems often miss biased wording and give users an inflated sense of “safety.”

For scholars who work with communities using non-standard English, or who intentionally quote historically situated or reclaimed terms, this has two implications:

You cannot assume that a grammar checker’s “inclusive language” label reflects rigorous bias analysis.

You should base decisions about wording on disciplinary and ethical guidelines, not on automated scores.

The tools can serve as prompts to review wording, but final decisions about fairness and representation remain human responsibilities.

Institutional Policies and Ethical AI Use in Academic Writing

Universities and research organizations are actively debating the place of AI in higher education. Survey work and institutional reports highlight recurring concerns:

Accuracy, hallucination and the risk of subtle errors that may go unnoticed

Data privacy and the possibility of student or faculty work being used as training data

Effects on critical thinking, self-expression, and academic integrity

Policies are still evolving, but many institutions converge on a basic pattern:

AI tools may be used for language polishing, provided that intellectual contributions remain the author’s own.

Use of AI in graded work may require explicit permission or disclosure.

Students and researchers are expected to take responsibility for any errors introduced by AI, including in grammar and referencing.

Before committing to a specific academic proofreading software, it is therefore important to read your local AI policy and, if necessary, ask supervisors or ethics boards how they interpret it.

Do You Really Need Extra AI Proofreading Tools for Academic Writing?

We can now return to the central question in concrete terms: if Word or Google Docs already offer spelling and grammar checks, do you actually need extra AI proofreading tools for academic writing?

When Built-In Checkers Are Enough for Academics

Built-in spelling and grammar can be sufficient when:

You are working on low-stakes or internal documents (emails, lab notes, informal handouts).

You usually write in your first language and have relatively few mechanical errors.

Your sentences are short and structurally simple.

You are dealing with highly sensitive data and cannot accept cloud-processing risks.

For these scenarios, it is reasonable to rely on built-in grammar checkers alone and to invest your time in careful self-editing rather than in configuring external tools.

When Additional AI Proofreading Tools Are Justified

External AI proofreading tools for academic writing become easier to justify when:

You are preparing high-stakes documents such as journal articles, dissertations, book chapters, or grant proposals.

You write in English as an additional language and know you struggle with certain categories of error.

You want systematic feedback on patterns that are hard to see on your own (for example, article use, prepositions or specific punctuation problems).

You have access to tools or institutional licenses that address privacy concerns.

In these contexts, adding an AI proofreading layer may reduce residual error rates and improve perceived clarity, even though it will not replace human revision or peer feedback.

The most realistic way to frame the decision is not “Which is the best grammar checker for academic writing?” but “Which combination of built-in tools, AI support, and human readers matches the risk level and constraints of this specific project?”

Conclusion: Do Academics Need Extra AI Proofreading Tools?

For many researchers, the practical question becomes: “Is Google Docs grammar check enough for academics, or should I add something else?” Built‑in spelling and grammar checkers in Word and Google Docs provide a reliable starting point. They catch typos and simple errors and are integrated into your writing environment.

Nevertheless, they may miss structural and semantic errors. AI proofreading tools for academic writing, like Grammarly, Paperpal, and Trinka are marketed as catching more mistakes and offering style suggestions, but they still leave gaps and introduce privacy and bias considerations. Research suggests these tools help some writers more than others.

Bottom line: For everyday writing and early drafts, built-in tools are often sufficient. For high-stakes documents—dissertations, journal submissions, grant proposals—adding a carefully chosen AI proofreading tool may improve clarity and catch additional errors. However, you should never outsource your critical reasoning or final judgment to a machine. Be transparent about your use of AI, comply with institutional policies, and protect sensitive data.

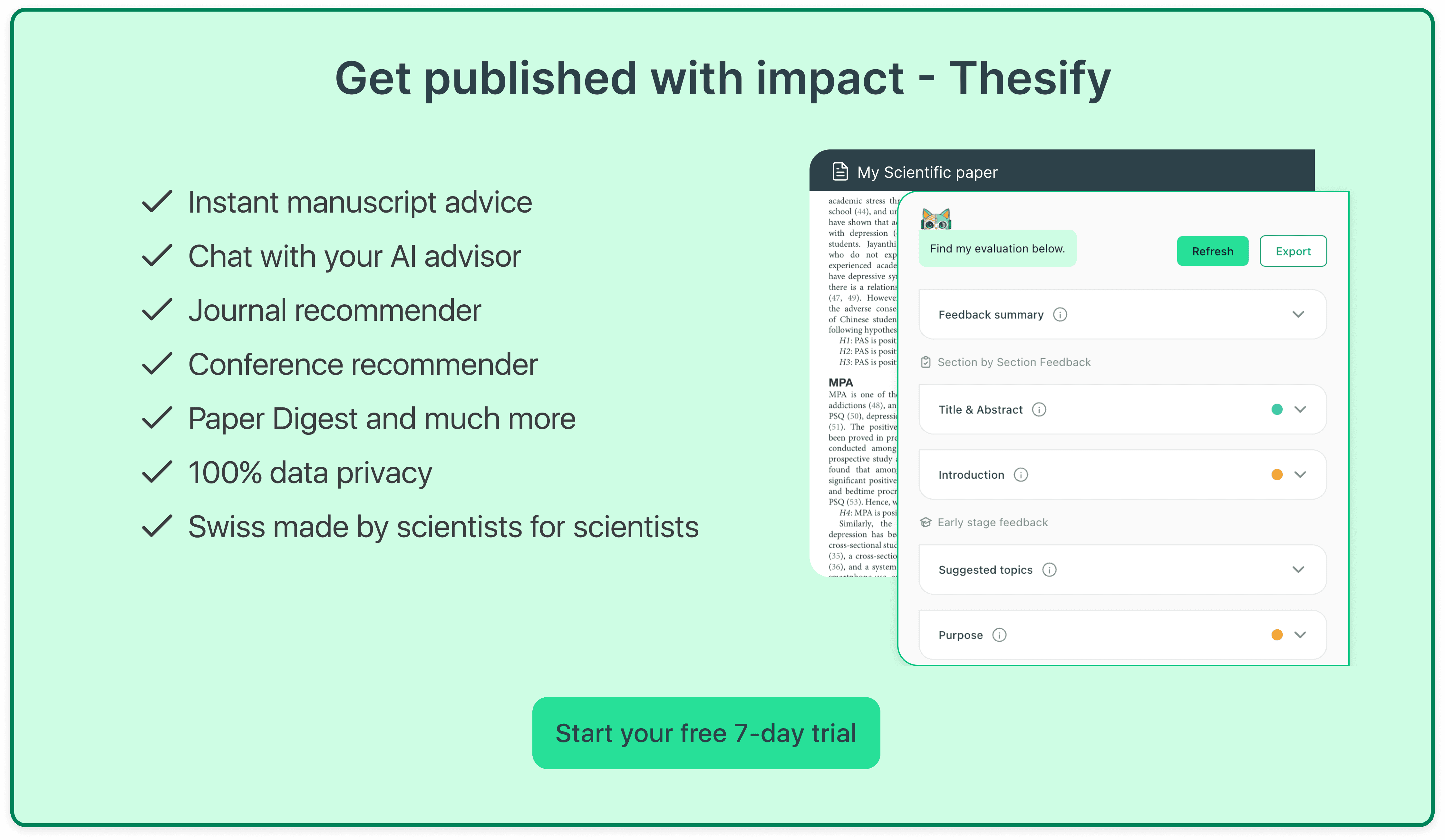

Use thesify for a Pre-Submission Check

If you want feedback on whether your article, chapter, or proposal is ready for peer review, you can sign up for thesify for free and run a pre-submission review on your next draft. You will receive structured comments on your argument, evidence, and overall framing, which you can then combine with whatever spelling, grammar, and proofreading tools you already use.

Related Posts

How to Preserve Your Academic Voice While Using AI Writing Tools: Learn how to use AI responsibility, without it changing your voice. Before large language models became a fixture in universities, writing assignments demanded hours of close reading, note-taking, and revision. In thesify's interview, Dr. Michael Meeuwis (Professor of English at the University of Warwick) reflects on what has changed and what is at risk when AI takes over that process. If your goal is to preserve your academic voice while navigating an AI-driven academic environment, the strategies included will help you write with clarity, integrity, and originality.

Understanding Differences in Academic Writing Across Disciplines: This guide walks you through discipline-specific academic writing in a systematic way. You will see how writing conventions in different fields shape structure, evidence, and voice, and you will get practical strategies for cross-disciplinary academic writing. The goal is not to memorize rules, but to recognize patterns so you can make deliberate choices that fit your project and your audience.

What Makes an AI Tool Academic? Evaluation Guide 2025: A PhD‑focused guide to choosing AI research tools. Understand evaluation criteria like source traceability, GDPR compliance, and fact‑checking. The market for AI research tools is crowded. Many resources simply list the “best” tools and rarely address academic integrity or evaluation criteria. This article covers the core criteria to consider when deciding whether to use AI in your academic work: source traceability, accuracy & fact‑checking, depth of analysis, specialization, and ease of use.